Photo: Shabbir Lakha

Photo: Shabbir Lakha

Locating racism as rooted in capitalism is key to building the kind of movement that can end it, argues Shabbir Lakha

The protests that began in Minneapolis in response to the brutal racist murder of George Floyd have spread like wildfire. In every US state, and 200 towns and cities in the UK and in most countries of the world, people have taken to the streets to call for justice for George Floyd and to say black lives matter.

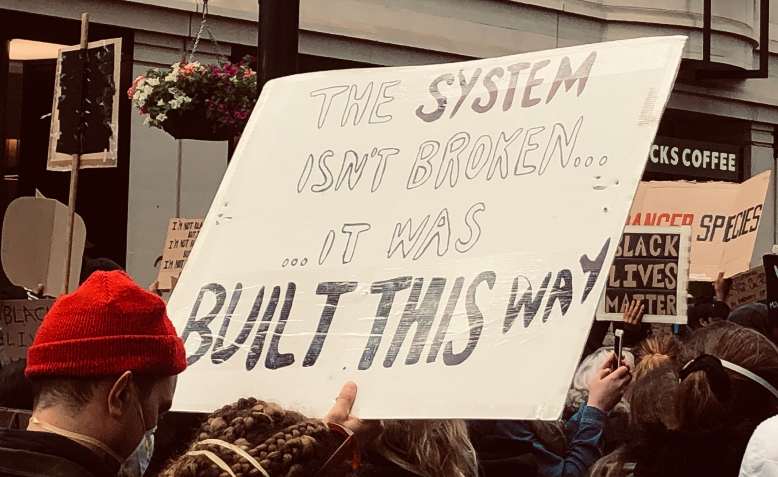

At any one of these protests, the speeches, the placards, in the numerous articles and tweets written about them, there is an acknowledgement that the racism being fought against is systemic, structural and institutional. Though these words aren’t interchangeable, there is a basic understanding that racism is deeper than individual behaviour.

But there is also talk of privilege, which moves the conversation precisely in the opposite direction. Privilege theory rests on the idea that there is a hierarchy of oppression in society and individuals benefit from privilege if they are not part of an oppressed group.

The idea can perhaps seem logical, but it creates a framework in which oppression is based on individualised experiences, rather than a product of a system or power relationship. This weakens our understanding of how to organise against it.

The systemic nature of racism

Racism as we know it can be traced back to the early development of capitalism and the centrality of slavery to it. Marx explained how the industrial expansion that was necessary to capitalist development depended on slavery:

“Without slavery you have no cotton; without cotton you have no modern industry. It is slavery that gave the colonies their value, it is the colonies that created world trade, and it is world trade that is the precondition of large-scale industry.”

Racism as an ideology – a pseudo-scientific conception that black people are sub-human – developed as a means for rationalising and justifying slavery. Eric Williams commented in Capitalism and Slavery,

“Slavery was not born of racism: rather, racism was the consequence of slavery”.

The Industrial Revolution was fuelled by slavery. The profits generated circulated in, and built, all parts of the economy. For example, companies like Lloyds of London, which were built on insuring slave ships. This went hand-in-hand with colonisation of resource-rich African and Asian countries to pillage and to develop new markets to sell the finished commodities to.

When slave revolts made it increasingly expensive and difficult to maintain slavery, capitalism adapted to sharecropping in the US and coolie labour from South and East Asia in the British colonies.

Even after the end of slavery, the need to maintain cheap labour remained, as did the racism that came with it. The modern state and its institutions that developed from this are deeply ingrained with this racist ideology.

Police forces in the US, for example, were set up to enforce slavery – to protect slave owners, and to catch and punish runaway slaves. Later, they enforced segregation and suppressed civil rights movements. Their role has been to use violence to protect the interests of the state and the racism of the state is institutionally embedded in it.

The racism of the state is replicated in all aspects of capitalist society and is rooted structurally from the law and criminal justice, to housing and schooling, to civil and labour rights. This structural racism is manifested in large part through the dimension of class. The vast majority of black and brown people in the UK and the US are working class. Their exploitation by the system is linked to their class position.

The coronavirus pandemic has brought to the fore the structural inequalities that exist and highlights how this relationship works. The disproportionate number of black and brown people dying from coronavirus isn’t because of some biological difference, but because being working class in this country means being more likely to have to work in those essential and manual labour jobs which continued throughout the lockdown, more likely to live in overcrowded housing and more likely to have underlying health problems. Because black and brown people are predominantly working class, they are disproportionately vulnerable.

Divide and rule

Fred Hampton of the Black Panther Party acutely identified:

“No matter what colour you are, you belong to one of two classes. There’s a class over here and there’s a class over there, this is lower, this is upper. This is the oppressed, this is the oppressor. This is the exploited, this is the exploiter. And this class [the former], they’ve divided themselves, they say ‘I’m black and I hate white people, I’m white and I hate black people, I’m Latin American and I hate hillbillies, I’m hillbilly and I hate Indians. So we fighting amongst each other.”

Racism is a tool of the ruling class to divide the working class and to stop them locating the root of their exploitation. It was a common feature of British colonialism as a means of maintaining its rule and, to this day, there remain deep-seated racialised tribal divisions in former British colonies as a result.

Domestically, the British ruling class stoked racism against the Irish as a racialised group in the 19th century. Marx commented that the antagonism between English and Irish working class people

“is artificially kept alive and intensified by the press, the pulpit, the comic papers, in short, by all the means at the disposal of the ruling classes. This antagonism is the secret of the impotence of the English working class, despite its organisation. It is the secret by which the capitalist class maintains its power.”

In the US, the First World War precipitated the expansion of urban cities as industrial hubs and the resulting demand for labour saw big waves of migration of black people from the countryside to join the industrial workforce. Black workers were paid a fraction of what white workers were, which is a benefit of racism for the bosses in itself, but it was also then used as a pretext to drive down wages of white workers. When this triggered a strike wave in 1919, trade unions refused to organise with black workers and the bosses brought in black workers from the South as strike-breakers. The strikes were defeated, the struggle for better pay and conditions for both black and white workers was quashed, but it sparked 26 race riots between white and black working class people that summer.

We’ve seen the same scenario play out over and over again throughout the last century every time those in power want to divide working people. When the Tories brought in austerity, cut the welfare of the poorest people in the country and presided over the slowest wage growth in 200 years, it wasn’t the bankers who were to blame. It was, we were told, the Jamaican nurse, the Polish builder and the refugee child drowning on a sinking rubber boat in the Mediterranean that were to blame.

When the government invaded the Middle East for its imperialist exploits, Muslims became terrorists. When black people object to being stopped and searched and arbitrarily arrested, they are thugs and criminals that have a tendency towards violence. This racism gets inflicted on racialised minorities through state institutions, and we can see overt examples of this in the Prevent counterterrorism strategy, policing, migrant surcharges at hospitals etc, and how it co-opts hospitals and schools into its apparatus.

But the ideas also permeate into society pedagogically. The media acts as one of the mediums through which the state can disseminate the racist ideas it needs to justify its actions. Racism is pushed downwards onto society from the top. This does of course have purchase, making the white worker blame the black worker for his low wages, or making the brown immigrant blame the Eastern European immigrant for waiting times at hospitals.

This racist discrimination carried out by individuals must be confronted and opposed wherever and however it expresses itself. Understanding that racism is rooted in the system and driven from the top does not mean excusing or ignoring individual discrimination. But it must be understood as a function of power – the power that the capitalist state wields to dominate the ruling ideas in society which it manipulates to protect its interests.

As Stokely Carmichael from the SNCC aptly put it,

“if a white person wants to lynch me, that’s his problem. If he’s got the power to lynch me, that’s my problem. Racism is not a question of attitude; it’s a question of power. Racism gets its power from capitalism.”

Anti-racism and privilege

The problem with privilege theory is that it ignores class and posits that there are people other than those at the top of society who benefit from oppression. In fact, as argued above, racism is used to divide working people for the benefit of those in power at the expense of both divided groups within the working class.

The idea that a white person who hasn’t experienced police brutality is privileged assumes as a starting point that it is a privilege rather than a right to not be racially discriminated against, and goes further to place that privilege on the individual instead of those who are actually benefiting from it. Its framework is based on accepting that there is a higher degree of commonality between people of the same race, regardless of their class position, than of people in the same class.

Is a white working class single mum using a food bank privileged compared to a black millionaire living in a mansion simply because she is white? Is the movement better served by a white anti-racist joining a Black Lives Matter protest, or by a black Tory MP that voted in the cuts that have hit black people the hardest?

Identifying shared experience as primarily race-based and not class-based is the principle upon which tokenistic responses to racism are generated. It was a black President of the US who deported more people during his term than any President before him. It was Sajid Javid who stripped Shamima Begum’s citizenship and Priti Patel who has carried on the hostile environment. It’s the Tory London mayoral candidate Shaun Bailey who said multiculturalism could make Britain a “crime-riddled cesspool” and who wants to put record numbers of police officers on our streets.

In the US, they are grappling with this question in a very direct way. For decades, the liberal elements of the movement have told black people that the way to create change is to vote for black people in elections, because a black person has the experience of racism and, in a place of power, they can make a change. Well, it was under a black president that the Black Lives Matter movement first erupted and in the towns and cities with black mayors, councillors, congresspeople, judges, working class black people are continuing to live in poverty, to be un-or-underemployed, to be killed by racist police.

Meanwhile, it’s white, black and brown nurses leaving 12 hour shifts to get teargassed while they treat injured protesters. It’s bus drivers that are refusing to let police commandeer their buses to transport arrested protesters. It’s white people standing alongside black people on the streets and standing up to the police and the national guard.

This is a question of practical anti-racism and the direction of the movement as much as it is ideological. Centering our understanding of racism around privilege helps to reinforce the divisions that the ruling class are creating and let’s them get away with it.

We can already see the attempts to do this. Boris Johnson says ‘black lives matter’ – but that those on the streets demanding it are extremists and thugs. We see the companies lining up from Amazon to Yorkshire Tea to say they oppose racism, the funds being set up to support black businesses and all manner of institutions talking about increasing diversity.

The fact that these things are happening is a testament to the power of the movement and just how much we frighten those in power. But it cannot become the strategic orientation of the movement.

If we recognise that racism is a product of class society, then in order to tackle it we need to diminish the power of the oppressing class. Our strength lies in the fact that the oppressing class depends on the working class to exist, and our class, as the majority of the people in this country, has the ability to take them on.

But this means building a movement with the biggest possible section of our class in it. We cannot win as a minority acting on its own. And unfortunately, that’s exactly what privilege theory does. It creates barriers of race-based experience and consigns even the best of those outside of the oppressed group as mere ‘allies’ and not as the active components of the struggle.

It also leads to further fragmentation of the movement – for example, when mixed race or Asian people are treated as separate from black people. In fact, they are also directly victims of racism. Islamophobia, directed mainly at Asian people in this country, has become central to ruling class ideology.

This only helps replicate the divide-and-rule so beloved of the ruling class. We need to build a movement that brings people into active participation based on solidarity. Instead of telling white working class people they’re guilty of the system’s crimes, our movement must explain that they are oppressed by the same racist system oppressing black people, and that it is both mutually beneficial to fight it and necessary to fight it together.

Of course, that means fighting every instance of racist discrimination in every workplace, institution and community – but that has to be a part of a wider struggle that is oriented towards taking on and tearing down the whole system.

Shabbir Lakha, Olivia Jones and Daniel Kebede discuss racism, class, privilege and capitalism

Join Revolution! May Day weekender in London

The world is changing fast. From tariffs and trade wars to the continuing genocide in Gaza to Starmer’s austerity 2.0.

Revolution! on Saturday 3 – Sunday 4 May brings together leading activists and authors to discuss the key questions of the moment and chart a strategy for the left.