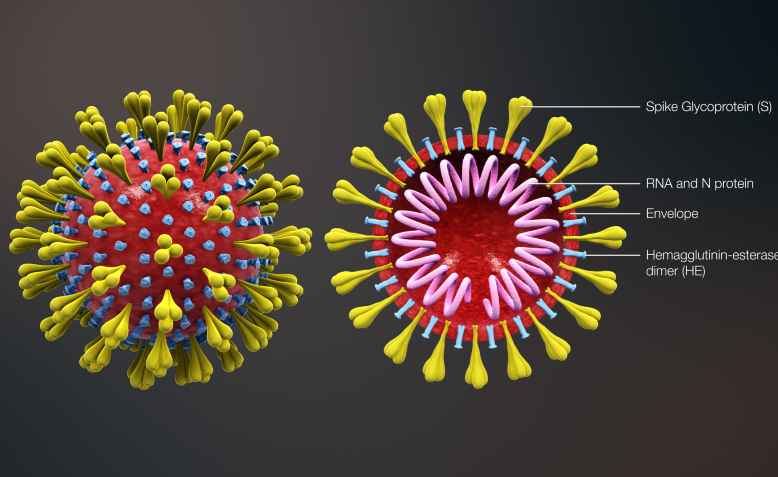

Coronavirus. Photo: wikimedia commons

Coronavirus. Photo: wikimedia commons

Solidarity, not stigma or division, is the key to beating this coronavirus, argues Lawrence Wong

We have already seen exceptional international collaboration which has resulted in the development of a test for the virus. Just 10 days after a pneumonia-like illness was first reported among people who visited a seafood market in Wuhan, Chinese scientists released the genetic sequence of the coronavirus that sickened them. That precious bit of data, freely available to any researcher who wanted to study it, unleashed a massive collaborative effort to understand the mysterious new pathogen that has been rapidly spreading in China and beyond.

At unprecedented speed, scientists are starting experiments, sharing data and revealing the secrets of the pathogen — a race that is made possible by new scientific tools and cultural norms in the face of a public health emergency.

“The pace is unmatched,” said Karla Satchell, a professor of microbiology-immunology at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

“This is really new. Lots of people [in science] still try to hide what they’re doing, don’t want to talk about what they’re doing, and everybody out there is like: This is the case where we don’t worry about egos, we don’t worry about who’s first, we just care about solving the problem. The information flow has been really fast.”

Twelve days after the genome was posted, NIH scientists published their first analysis, showing that the coronavirus used the same door to get into human cells as SARS. About 12 hours later, a Chinese team of scientists who had isolated the virus from patients showed, using the actual virus, that the team was correct. On 23 January, once human to human transmission was confirmed, the Chinese government, upon advice from its health professionals, declared an unprecedented quarantine in an effort to contain the virus.

The Chinese government had learnt from its past mistake of attempting to conceal the 2003 SARS outbreak. When SARS began to spread, the tools scientists needed were much less mature, including the basic infrastructure for sharing results rapidly so anyone could build on them.

The current collaboration would have been almost unthinkable when researchers were working on SARS. Imagine walking from London to Istanbul, and then imagine taking a plane from London to Istanbul. That’s kind of the difference.

Alongside this wonderful collaboration and solidarity runs anti-Chinese racism stirred by the media, governments, and racists. Last Sunday, a group of Chinese students formed Chinese Against Racist Virus to protest against reports of anti-Chinese verbal abuse, physical assaults, and avoidance of Chinese people and businesses.

The banner said that Chinese are not a virus, racism is. The protest also included East and South East Asians who have experienced racist abuse. Yesterday, an Asian woman was knocked unconscious for standing up to racists who were abusing a Chinese friend of hers.

As the virus spreads to Italy, Iran, South Korea, and the Middle East, we have been fortunate that only thirteen cases of COVID-19, four of which were ‘imported’ by the British government, have been confirmed in the UK. Further spread of COVID-19 appears to have been prevented and it has been contained in China. The solution to public health emergencies remain containment, hygiene, and education. A vaccine is at least fifteen months away. If COVID-19 were to spread uncontrolled in Europe, we will see increased racism and greater solidarity will be needed to repeat that Chinese are not a virus, racism is. 21 March is a good place to start protesting on the UN anti-racism day.