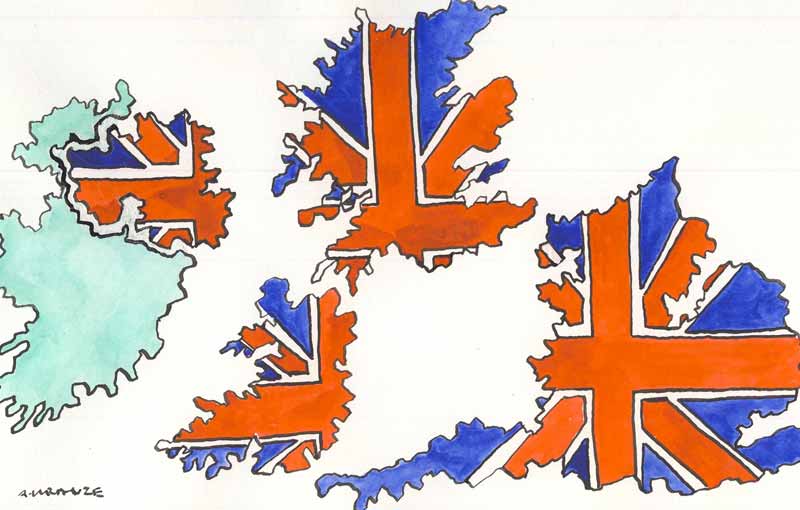

Illustration by Andrzej Krauze

Illustration by Andrzej Krauze

Guest contributor Mark Perryman offers a personal contribution to debates about the implications of the Scottish referendum

In a recent Counterfire article on the Scottish referendum campaign Alex Snowdon used a rarely mentioned phrase, the ‘English Left’. Apart from a few mavericks, amongst whom I number myself, who have been arguing for a progressive Englishness for the past few years, this is a prefix that up to now the Left seemed distinctly uncomfortable with.

While language is important, politics cannot be reduced simply to the words that we use. But, in the aftermath of Scotland’s historic referendum, recognising a break of the Union as a vital stage in transforming Britain’s ancien regime of establishment, monarchy and privilege must in part define Left politics north and south of the border (Wales and the North of Ireland too).

A 45% vote for independence is quite extraordinary. All three parliamentary parties, with UKiP following close behind, the entire media establishment (with the solitary exception of Scotland’s Herald newspaper), the full weight of the business and finance sectors, were ranged against Scottish independence. We now have a Scotland in which 45% of the population no longer want to be part of Britain.

On the ‘No’ side substantial parts of that vote voted against independence but for increased devolution of powers to the Scottish Parliament. The pressure will now be on Cameron, Clegg and Miliband to implement their ‘vow’ of increased powers, in the face of fierce Tory backbench opposition and some from Labour’s backbenches too. In short, after yesterday, the process towards a break-up remains irreversible.

The Left in England’s temptation will be to return to ‘business as usual’, the last few weeks treated as a temporary aberration. Nothing could be more mistaken. Scotland’s political discourse is now not only markedly different to Westminster’s; the trajectory towards a break-up will continue to have a decisive effect on English politics too. The Left in England should be at the forefront of recognising and encouraging this reality. We can do that by not only celebrating and encouraging the Scottish Left’s efforts in the direction of independence, as many of us did during the Referendum campaign, but by recognising that if we favour the break-up then an English Left is what we are not a British one.

How might that process begin? The vocabulary we use for starters, but something deeper too. We have a rich tradition of new Left writers on the subject – including EP Thompson, Benedict Anderson and Tom Nairn (more recently Gary Younge, Linda Colley and more too). There is a rich tradition of Left historians engaging with and exploring England’s radical past, including Christopher Hill, Brian Manning and many others. Knitting such ideas into our politics, renovating them for the post-referendum era, would be a good starting point.

To drop the long-held default position of throwing our hands up in collective horror at any mention of English identity would be another. To seek creative, popular ways to shape that identity of purpose, most crucially to give it a civic dimension divorced from the racism it has traditionally at least in part been shaped by. Migration and race will be core to any English politics, in a way they are not in Scotland, for the foreseeable future. An Englishness which celebrates our multiculturalism, our history as a ‘mongrel nation; shaped by trade and empire, is no mean feat but if we don’t try then what kind of future are we not looking forward to?

Of course England’s politics will never be shaped by the ‘national question’ in the same way as Scottish politics are. But the post-referendum terrain will see the Union and its doleful consequences continue to be a key issue. Labour Unionism has sided, as always, with the defence of the status quo. Brown, Miliband and Darling were bag-carriers for Cameron during the course of the Referendum campaign. A Scottish Left will undoubtedly continue to challenge Labour Unionism north of the border with real prospects of an electoral breakthrough under Proportional Representation in the 2016 Scottish Parliamentary Elections.

In England we also need to be challenging Labour Unionism, not in the first instance in the electoral arena but through ideas and actions. Any English Left needs to learn lessons from the Scottish Left’s imaginative embrace of the cultural dimension through such referendum initiatives such as the National Collective. Going way beyond the ‘ninety minute nationalism’ that has seen football, the England team, offer almost the only visually popular way of identifying with England.

A dynamic and youthful Left, inspired by a national narrative but not trapped by it. Look at the Radical Independence Campaign happily not only co-existing but co-operating with the creative pluralism, of thinkers such as Gerry Hassan, without much, or any, of the mutual suspicion or jockeying for position in England leftist politics is more usually associated with. The simple process of learning from others will help to de-centre Englishness from its London and south-east cultural fortress in the most radical and unpredictable of fashions.

And where do we start? By recognising who we are: an English Left, not the British Left. Internationalists to the core, we have a world to win, and our nation to change for the better too.