The story of an active life during momentous times from the Cold War to the 1980s turns out to be more personal than resonating with the political, finds Jacqueline Mulhallen

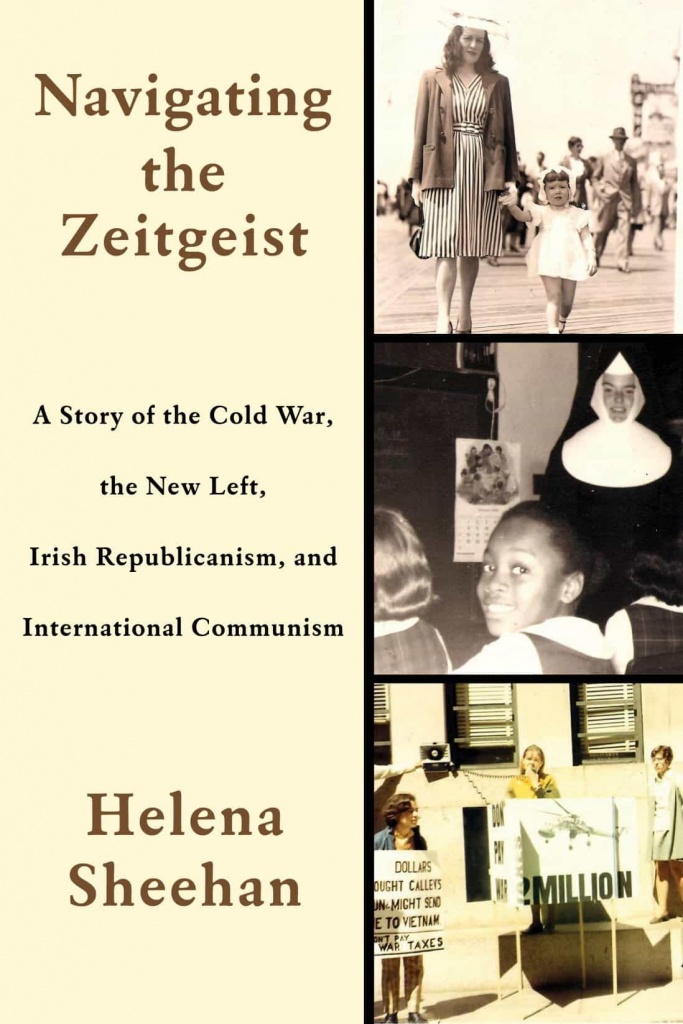

Navigating the Zeitgeist with its subtitle, ‘A Story of the Cold War, the New Left, Irish Republicanism, and International Communism’ suggests rather more than is delivered. Yes, it is a story – one person’s experience as a small part of all these things, but it is more personal than political. It is very difficult to write a personal autobiography that is also a history of a movement – such as Sylvia Pankhurst’s The Suffragette Movement, for example. Helena Sheehan’s book is not really that, but her life was certainly full of political and ideological variety.

Before reading this book, I had not heard of her. She has taught at Dublin City University and has written several books: a philosophical work, a book on the media and one on Syriza. Now in her 70s, her life is dealt with in this autobiography up to the age of 44, ending in 1988. Born into a large working-class family of Irish descent in Pennsylvania, Sheehan was brought up with strict Catholicism and brutal discipline. She showed signs of rebelling in her teens.

Despite the disapproval of her parents, she began campaigning for John Kennedy in the 1960 elections; despite their racism she went out with a young black man, visiting ‘neighbourhoods considered dangerous, especially for a young white teenage girl’ (p.41); and she skipped her typing lessons to read in the public library. All the more strange that she should then decide she had a vocation to become a nun, especially as she ‘seethed in contempt for the conformism and mediocrity’ (p.44) of her parents’ generation and said she wanted to join the Peace Corps and go to university. She explains her decision by citing ‘the grip that Catholicism had in those days’ (p.42) and that she felt confident of the church’s omniscience’ and felt ‘called’. But she couldn’t accept the many restrictions placed on her as a novice, although she began teaching which she enjoyed. Indeed, it is strange that she actually made it through her noviciate when she had so many misgivings, but after a long discussion with an old friend, a priest, she realised that she wanted to leave. She was to repeat twice more this pattern of deciding to join a monolithic, old-fashioned and hierarchical organisation despite having reservations: one was the Official IRA and the other the Communist Party.

The period in the convent enabled Sheehan to get teaching jobs and to study at university. Here, she married despite not believing in the institution of marriage, and the marriage did not last. During the late 60s she became politically involved in the anti-war movement and with civil rights, black power, and feminism. She was in a whirlwind of demonstrations, leafleting, meetings, street theatre and be-ins. She also began a PhD in philosophy. It is in this part of the book that Sheehan seems most connected to issues that were gripping the world and her own generation at the time, but she found the movements too amorphous and disorganised and disliked the hippie element with its ideas of eastern religions, going back to the land, and drugs.

Irish politics

At the end of this period, Sheehan also became interested in Irish politics and after organising meetings for IRA speakers in America she decided to go to live in Ireland where she joined Sinn Fein and the Official IRA, despite misgivings about violence. After a visit to the north, and after several friends were killed, she resigned and joined the Communist Party.

It appears she threw herself into argument in both these organisations and read a great deal. She gave up her PhD and started another one, at Trinity College Dublin. She had meanwhile married for a second time and had two children, and she struggled with managing both her life of political debates, writing and teaching and her PhD. She travelled to the Soviet Union and countries such as Czechoslovakia and East Germany, at one time spending four months in the USSR. She became disillusioned with the Stalinist line and began investigating the 1930s purges, the 1968 invasion of Czechoslovakia and other matters. There is a sense of name-dropping about people she met and even just saw – such as Howard Zinn glimpsed giving a lecture. Frequently, people are mentioned who, I accept, might be well known in the Communist Party, but since I had not heard of them, I could not appreciate the importance of her discussions with them. She mentions that Trotsky was a bad word in her circle, but her researches into the history of communism appear not to have taken his writing on board and one senses that Trotsky is still suspect to her. She finally left the Communist Party, completed her second attempted PhD, which was highly praised, and joined the Labour Party, finding a group who wished to make it more ‘Marxist’.

Unfortunately, this is hardly a story of the times, let alone a political history. In Ireland, during the period following Bloody Sunday, many joined the Provisional IRA, but Sheehan joined the Official IRA. Events such as the Sunningdale Agreement are not mentioned; the rise to power of Thatcher and her hardline attitude towards the IRA is not explained; and the numerous shootings, bombing campaigns, the issue of political prisoners, including the dirty protests and the hunger strikes, are not discussed. Yet at the time, these were a matter of daily discussion for virtually everyone, whatever their politics.

Sheehan mentions that she welcomed Chilean refugees to her house, but not the events of 1973, something also widely discussed at the time. She does mention supporting the struggle against apartheid and meetings that her husband has on Palestine, but not in any detail. The Portuguese revolution may as well have not happened, nor the rise of CND. She mentions martial law in Poland, but there is only a brief discussion of the Solidarity movement and none of the excitement it caused. In fact, everything that interested me politically in the 70s and 80s is absent and is replaced by a tale of meetings and conferences in the Communist Party. Far from being an exposition of the ‘spirit of the times’ (Zeitgeist), Sheehan’s discussions appear to me to be abstract and unconnected with what was actually happening.

A personal history

The argument and hostility in Sheehan’s life appear to have left a need for self-justification and settling scores. These may in some cases put the record straight, but other complaints seem trivial, given the serious mistakes made by the organisations she has supported. For example, she says that ‘Ireland seemed like a backwater’ (p.275) and criticises Trinity College, Dublin, which accepted her as a PhD student, for its name and its ‘quaint vocabulary’ (p.191) and, without any real comparison of the two systems, the way in which its education system differed from that of the USA. Even unemployment benefit and those claiming it are criticised, though it is a right that workers have fought for. Considering that a number of years elapsed before she finally abandoned her first PhD, for which she had funding, it is hard not to sympathise with an ironic remark made by her supervisor, and when her husband, a convinced Communist Party member, said he did not want to type any more of her work criticising the Party, it is not surprising, especially since they had joined the Party together.

Sheehan appears to be a woman of courage, but she has also had a great deal of support and privilege and has been able to travel widely. Although at the end of this volume she is finding it hard to make a living and has separated from her second husband, she is in another relationship and is writing and teaching rather than working as a cleaner or a typist or in a factory. I suspect that her

planned second volume will reveal that she gets a more permanent job, but, given what is left out of this book, she will be unlikely to address and clarify the major events of more recent times.