Danell Jones’ biography of an African man living in Edwardian London reveals a remarkable life amid the racism and imperialism of the time, finds Jacqueline Mulhallen

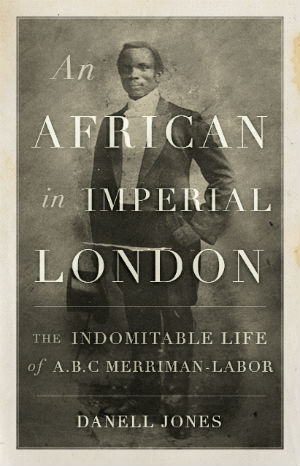

Danell Jones, An African In Imperial London: The Indomitable Life of A. B. C. Merriman-Labor (Hurst 2018), 309pp.

Danell Jones has written a brilliant biography of someone I had never heard of – and I am sure that many others would not have heard of, A.B.C. Merriman-Labor. He wrote only one book that has survived, Britons through Negro Spectacles, which is available to read online.

Merriman-Labor was born in Sierra Leone in 1877. He was highly intelligent, witty and a popular member of that part of Sierra Leone society descended from liberated African slaves and known as the Krios. His social life included entertaining people with magic tricks. His father was, among other things, a printer, and writing attracted young Merriman-Labor. His grandfather was a famous teacher and his uncle was editor of the Sierra Leone Guardian. Merriman was a junior clerk in the colonial office and was expected to have a successful career. What is more, he managed to get a rise for himself and the other workers.

He was also a keen observer of colonial/British relations, particularly when there was a disastrous military intervention in Sierra Leone. Taxing the local indigenous people was so unpopular that taxes had to be collected at the point of a gun. A British army officer decided to arrest a local chief who proved more than a match for the British army: he rallied thousands of warriors and they defeated the British again and again. Although he was eventually captured, it was not until several months had passed. Merriman-Labor wrote a witty commentary, anonymously, calling himself an ‘Africanised Englishman’ who had been in the colony twenty years. That part was true. Merriman-Labor was then twenty years old!

Lawyer and writer

Many Africans went to London to get a law degree and returned home to hold prestigious posts in their own countries. But Merriman-Labor had his sights set on something more; he wanted to succeed as a writer. So, although he set off for London in 1904 to study at Lincoln’s Inn, he wanted to absorb much more than the study of the law. He also wanted to study the customs, manners and life of the inhabitants of London. This he did, and in fact he became a popular and important figure in Edwardian London, well-liked by the black community and with many friends among the white population too. He was taken on outings by a hospitable couple to see Hampton Court, Greenwich and other sights as well as to Herne Bay in Kent. He was befriended by a bookseller who helped him get a reader’s ticket to the British Museum and to find cheaper lodgings. He learnt to speak English without a West African accent from ‘intelligent ladies of the middle class’! (p.50). He joined a select club, met the Speaker of the House of Commons and was invited to attend a debate in Parliament.

Merriman-Labor also had close friends among Africans and he described his activities in bulletins to newspapers in Sierra Leone. July was hot enough for Africa, but the intense cold of winter, the snow, the skating, the fog, were all impressive. Although he encountered casual, vile racist remarks from people in the street on occasion, he appears to have met little racism at the hotels and boarding houses where he stayed. The only time he experienced it was when an American family asked if he would leave the dining room while they had their dinner. When Merriman-Labor refused, saying that as a British subject he had a better right to be in the dining room and in the country than they had, it was the Americans who had to leave the dining room instead.

Merriman-Labor was instrumental in the celebration of the one hundredth anniversary of the abolition of the slave trade, attending Westminster Abbey and laying a wreath on the tombs of William Wilberforce and others, in the presence of their descendants and many African and Caribbean dignitaries. He attended many conferences on the situation of the African colonies and African British relations, where he sometimes also spoke. He was present at the funeral of Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, the great Edwardian composer whose father was Nigerian.

The African General Agency

However, Merriman-Labor was not rich and in order to support himself while he was studying at Lincoln’s Inn, he set up a trading company called the African General Agency. This was to be run on co-operative lines and he looked for benefit for all African countries. Merriman-Labor had already expressed disgust at the way the resources of African countries were exploited by the imperial countries. He wanted Africans to be able to control their own resources and trade on equal terms with European countries. Of course, this was not going to be allowed by the imperial powers, and in any case Merriman-Labor’s ideas of co-operation within capitalism was not likely to last either.

Nevertheless, his company was actually very successful. The problems came with Lincoln’s Inn. To the horror of the ‘benchers’ who ran the college, they found out that one of their students was actually engaged ‘in trade’, rather than being supported by private means. Merriman-Labor was forced to turn his enterprise into a limited company, thus losing £100-£200, a great deal of money in Edwardian London. That, however, was not as bad as having to lose the income he was earning from the company. Nevertheless, to Merriman-Labor, the importance of having his law degree was greater than a career as a businessman. If he were not able to continue his life in London, he would always have been able to return to Sierra Leone and have a career in the colonial office, where he had been well respected for his earlier work. So, he was willing to make the sacrifice of both in order to retain his law career. But there was more to come.

Observing the British

To make up for his loss of income, Merriman-Labor hit on the idea of returning to Africa and giving lectures about Britain, accompanied by lantern slides. This was very successful indeed. He seems to have been an excellent speaker and the lantern slides were very good. He achieved his goal and returned to England with money in his pocket and an idea for a book, which became Britons Through Negro Spectacles. Yet no publisher would take it. They acknowledged its originality, but they did not want books which were ‘too’ original.

So, Merriman-Labor published it himself.He was expecting a great sale in Africa. However, sales were not good, although the book had some good reviews. Merriman-Labor was forced to leave a job because the firm was fraudulent, and although he received compensation eventually it was not as much as he expected. He had tutored students from Africa in the law, but now fewer students were coming to London. He owed the printers of his book, and he had no income. Furthermore, a relatively trivial complaint about him was made to Lincoln’s Inn, and Merriman ended up by being disbarred, almost certainly because of racist attitudes in the legal profession.

Bankrupt, disbarred andin a country at war, Merriman-Labor worked in a munitions factory throughout World War One. All this had a deleterious effect on his health, and in 1919 he died of tuberculosis. A sadly short life, and with only one book to his credit that has survived. This is a life that many would consider to have been a failure, but, considering what was stacked against him, that was not the case. To have become a figure of significance in Edwardian London with many friends, both black and white, was an achievement in itself, and the part he played in encouraging Africans to trade on terms of equality with the imperial powers must also have left its mark. His contribution to conferences andto the commemoration of the abolition of the slave trade were also important, and he wrote a regular letter from London to the Sierra Leone Guardian for many years.

While Merriman-Labor was no Marxist or even a socialist, the book tells us a great deal about the world he lived in, and about attitudes in both African and Britain at the time. All of this throws light on the racism and imperialism of the day, at the root of notions which are still influential today. Because of this imperialist inheritance, it is important to highlight the achievements of African writers of any era, as it is of any oppressed group.

The biography is well-written, and although some of the conclusions are necessarily speculative since few documents can be traced, they are always very well-grounded and probable. His biographer has given a vivid picture of London one hundred years ago, and the way in which Africans and Caribbeans were beginning to question colonialism, to band together and work for independence. Merriman-Labor played a part in this and should be honoured for his attempt to make sense of colonialism and imperialism, and for what his uncle described as his ‘indomitable’ attitude to life.