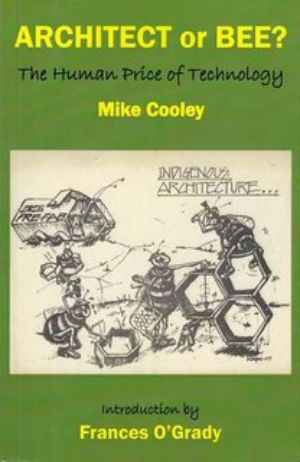

Mike Cooley’s Architect or Bee? put the case that a new organisation of technology could provide social good rather than profit. Orlando Hill welcomes the new edition

Architect of Bee? The Human Price of Technology, introduction by Frances O’Grady (Spokesman Press 2015), 200pp.

‘A bee puts to shame many an architect in the construction of her cells. But what distinguishes the worst architect from the best of bees is this, that the architect raises his structure in imagination before he erects it in reality. At the end of every labour-process, we get a result that already existed in the imagination of the labourer at its commencement.

Karl Marx Capital, vol. 1, ch. 7.

I was made aware of Architect or Bee? by Mike Cooley in a meeting organised by North London Stop the War and CND. The meeting was called to discuss the forthcoming Stop Trident demo on 27 February. One of the issues raised was the effect scrapping Trident would have on employment. It was pointed out that Unite and GMB were in favour of renewing Trident as a way of securing jobs. On the GMB website, Gary Smith, GMB Scotland Acting Secretary, defends the renewal; ‘GMB Scotland will not play politics on this and will stand up for our defence workers and their communities right across the UK.’ In his opinion, any promises of alternative jobs are pie in the sky based on ‘Alice in Wonderland politics.’

These ‘pie-in-the-sky jobs’ are exactly what Cooley discusses in his book, which was first published in 1980 and has recently been republished with an introduction by Frances O’Grady, General Secretary of TUC. What would the skilled and creative defence workers wish to provide if they had the choice? If they were given the opportunity to be ‘architects’ and not just ‘bees’. Surely it would not be weapons of mass destruction.

The workers at Lucas Aerospace were forced to answer that question in the 1970s when they were faced with the threat of structural unemployment. Similar to the defence workers in Scotland, they were also producing products that society did not want. From this realisation the idea of a campaign for the right to work on products that society genuinely needed and wanted evolved.

‘It seemed absurd to us that we had all this skill and knowledge and facilities at the same time as society urgently needed equipment and services which we could provide, and yet the market economy seemed incapable of linking the two’ (p.117).

The workers sent a letter to various organisations and institutions asking a simple question: ‘What could a work force with these facilities be making that would be in the interests of the community at large?’ (p.118) The result was a range of products valued for their use and not merely for their exchange value. After a visit to a centre for children with spina bifida, a vehicle was designed to help children with this condition to be independently mobile. Some members at another plant developed a light-weight portable life-support system which could be taken in an ambulance after realising that 30% of people who die of heart attacks die before they reach the intensive-care unit. Many other similarly useful products were designed. Sadly, not all were manufactured due to their incompatibility with the objectives of the market economy.

Cooley argues that if we are going to move from merrily producing commodities to producing goods that people need and want, we must change our attitude towards technology. The technology used today evolved from the concept of the division of labour. In a capitalist system in which the maximisation of profit is the sole objective and people are regarded as units of labour-power, the division of labour and fragmentation of skills is absolutely rational and scientific. However, the consequence is the deskilling of workers and alienation from reality. A division between theory and practice is created with a bias towards theoretical knowledge. The skill and practical knowledge of the worker is despised.

This growing separation between theory and practice generates confusion between linguistic ability and intelligence. If a student cannot explain how they did something, it must mean they do not understand. There is something called ‘tactic knowledge’ which our society disregards. Tactic knowledge is acquired through doing or attending to things. Cooley argues that due to our over dependency on computerised equipment we have lost the feel for the physical world around us. Work has become abstracted from the real world. Cooley is a strong believer that work is vitally important for human beings, but not the grotesque, alienated form that we see in a production line. Work is vital for human beings when it links hand and brain in a meaningful and creative process, balancing the manual and intellectual.

Cooley questions whether technology developed under a capitalist mode of production can be used to develop flexibility and creativity. Computer-aided design programmes could be used to democratise the decision-making process in architectural design. However, when these programmes are appropriated by the owners of the means of production, they are used to further alienate the designer, leading to a fragmentation of the design skills and a loss of the panoramic view of the design activity.

The designer becomes subordinate to the machine. The objective decision of the system, which is quantifiable, dominates the subjective value judgement of the designer, which cannot be quantified. According to Cooley ‘we still have the time and indeed the responsibility to question the linear drive forward of this technology’ (p.72). It would be interesting to know if in the thirty-four years since the book was first published whether we have managed to save any of this technology from that linear drive.

The practical necessity of trying to adapt forms of technology developed under capitalism, instead of creating entirely new ones, might have been one of the serious problems of the Soviet Union in its early years. In 1918, Lenin argued that:

‘the possibility of building socialism depends exactly on our success in combining the Soviet Power and the Soviet Organisation of Industry with the up-to-date achievements of capitalism. We must organise in Russia the study and teaching of the Taylor system [maximising workers’ productivity through time and motion studies], and systematically try it out and adapt it to our ends’ (p.94).

Lenin’s view could be argued to be uncritical towards technology, but the context of the new soviet state’s extreme vulnerability to western imperialist intervention, and the depth of the economic crisis due to World War I, put severe limits on the revolutionary government’s options.

Nonetheless, it is clear that a different approach to technology could open up again a new vista of possibilities for an alternative economic system. Cooley envisages that socialism would be able to liberate workers from the constraints of capitalist technology:

‘Socialism, if it is to mean anything, must mean more freedom rather than less. If workers are constrained through Taylorism at the point of production, it is inconceivable that they will develop the self-confidence and the range of skills, abilities and talents which will make it possible for them to play a vigorous and creative part in society as a whole’ (p.94).

In part, this point is contradicted by Cooley’s own story, as the Lucas Aerospace workers were precisely able to demonstrate the ‘self-confidence and the range of skills’ to imagine, like Marx’s architect, ‘a vigorous and creative part in society as a while’ in practical ways. Yet, to make their consciously imagined plans a reality, we must indeed struggle for a socialism that can design and organise technology for the benefit of all human lives, and not just for the production of commodities for profit.