The stories of the Calais refugees reveal their struggles and solidarity, as well as their experiences of racism and oppression, finds Tom Griffiths

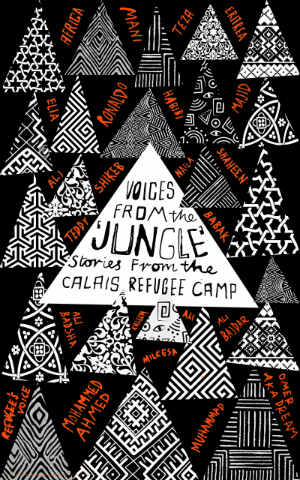

Voices from the ‘Jungle’: Stories from the Calais Refugee Camp (Pluto Press 2017), 258pp.

If one piece of recent history and one geographical location would have to suffice as a symbol of the failures of Western liberal democracies as regards the great refugee crisis of our time, it’s the Calais ‘Jungle’ in 2015-16. Grown out of a reclaimed landfill site within sight of the English Channel it became home to tens of thousands of refugees, in what became a place synonymous with poor living conditions, hunger, riots, police violence, inadequate water supplies and worse sanitation all within hours of Paris and London, supposedly some of the most ‘civilised’ places on earth.

I made that journey twice on delegations from the People’s Assembly as we were organising our ‘Convoy to Calais’ in the summer of 2016, a major relief effort in its own right and also a powerful political intervention on the side of the refugees and migrants who had become trapped there and abandoned by the British, French and other EU authorities. Starting the day in London and going to bed safe and warm in my Hackney home by nightfall was a surreal experience, all this unnecessary suffering, so close that you could be there and back in a day.

While many of the volunteers who had moved there to be on site had lots of fascinating things to say about their experiences, of course the refugees and residents of the ‘Jungle’ themselves had to be heard. These ordinary people came from some of the most unstable and violent regions of the globe, in many cases as the direct result of Western military interventions. They had undergone incredible and often dangerous and always hard journeys, to find themselves butting up against racist and uncaring governments, whose attitude to these people was first to ignore, second to demonise and lastly to brutalise.

That the individuals I spoke to who were living in the camp were not crushed by all this was impressive, but like all people everywhere in dire circumstances there was humour, fighting spirit and solidarity. While the ‘Jungle’ was clearly a hard place to live, they had also made incredible efforts with scant resources to make the place a home, and also a community. These people were some of the most positive and tenacious I have ever met. But they were also hungry, hungry all too often for food, but also for freedom, to be able to go where they please, for a peaceful life, unmolested by the racist and bullying French Police, hunger for family, and also for education.

This important book speaks of those hungers, and is born out of the strong impetuous of many in the camp to educate themselves (many had had university education cut short by war and hardship in their home countries). Supported by the University of East London, volunteer organisations and most importantly the refugees and residents themselves, a project was begun to record as many of the individual stories from those that had lived them as possible. Started as an education initiative the result is this text which short of going to the ‘Jungle’ (now longer possible) is the best way to hear the voices of those that lived through this first hand. The book is co-authored by a group called the ‘Calais Writers’ include Africa, Riaz Ahmad, Eritrea, Ali Haghooei, Babak Inaloo, Mani, Milkesa, Shaheen Ahmed Wali, Shaqib, Teddy and Haris Haider, who are all former inhabitants of the Calais refugee camp.

As the authors explain in the introduction, it is structured in a semi-chronological fashion; with sections such as Home, Journeys, Living in the ‘Jungle’ (Arriving, exploring and Settling in), Leaving the ‘Jungle’, Life after the ‘Jungle’, and so on, trying to give the fullest picture possible. Many people tell stories of experiencing violence and persecution from the Taliban, Daesh and Al-Qaeda and others, of trying to carve out a life in war-torn Afghanistan and many other Middle-Eastern countries. There are stories too of attempts to enter Europe from the east and playing cat and mouse with ruthless Bulgarian police units, and frightening accounts of crossing the Mediterranean to arrive in Sicily from the North African coast. There are, of course, accounts of hardships and police oppression in the ‘Jungle’ itself. That said perhaps some of the most moving passages are from those that found beauty around them. One resident from Sudan writes:

‘I have been here for three months, in this wonderful world the ‘Jungle’. Really it is wonderful, Because of the people inside, they are wonderful.

You can see many nations, saying, ‘Hi, hello,’ in different languages. You can see in their eyes that they respect you’ (p.153).

Such respect was not afforded to these individuals trying to find peace in France and in the UK, and since the camp was demolished stories are constantly emerging of whole families sleeping rough in the French countryside. It’s time to show them the respect they deserve, let them all in and afford them equal rights and opportunities when they’re here in the UK. The best chance we have of doing that is to keep doing everything we can to get this racist, war mongering Conservative government out of office. And that is now entirely within our grasp. In the meantime, please read this powerful book, one way we can respect each other is to listen to each other, Voices from the ‘Jungle’ gives us the opportunity to do just that.