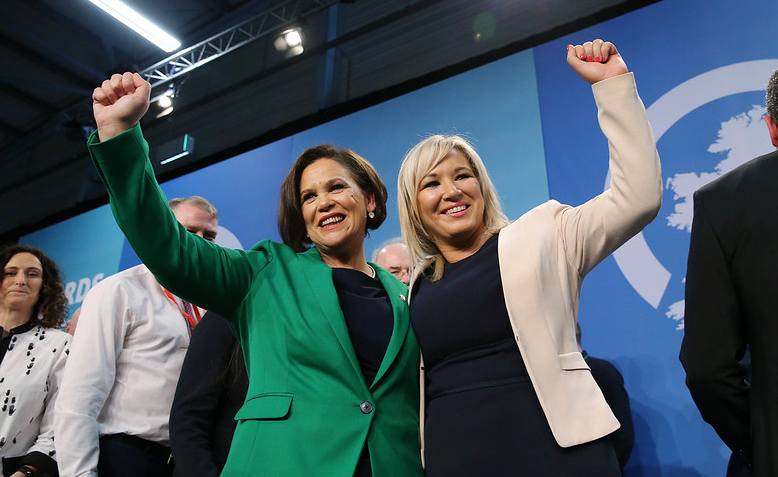

Sinn Féin President Mary Lou McDonald and Vice President Michelle O'Neill, Photo: Sinn Fein Flickr / cropped from original / licensed under CC BY 2.0, linked at bottom of article

Sinn Féin President Mary Lou McDonald and Vice President Michelle O'Neill, Photo: Sinn Fein Flickr / cropped from original / licensed under CC BY 2.0, linked at bottom of article

Chris Bambery looks at the remarkable success of the Irish nationalist party and considers what it means for politics north and south of Ireland

The success of Sinn Féin in becoming the biggest party in Northern Ireland is a seismic change in a state created in 1921 to create a permanent, unchallengeable unionist majority. It will also create a headache for both the governments of Britain and the Republic of Ireland.

Part of the reason for the Republicans’ success is demographics, Catholics are now probably the majority within the six county state. That could not have been seen as remote possibility in 1921 when six counties were separated from the nine counties of Ulster and from the 26 counties of what is now the Republic of Ireland in order to ensure the unionist majority.

But the other part is the disintegration of the unionist monolith. The Unionist Party ran Northern Ireland as a one party state, giving no say to the nationalist minority and discriminating against them in terms of jobs, housing and voting rights, from its inception until 1972 when Britain abolished the separate Northern Ireland government because its repressive response to the civil rights protests of 1968 and 1969 had flared out of control into the Troubles.

Since then the once all powerful Unionist Party has virtually disappeared, eclipsed by its rival, the Democratic Unionist Party, founded by the Reverend Ian Paisley in 1971 on an even harder line towards dealing with the emerging Provisional Irish Republican Army and in trying to drive the nationalist minority back into servitude.

But for over a year the DUP has been tearing itself apart in a series of bizarre faction fights involving its leadership, caused by Brexit. It lost a considerable amount of its vote to the hard line Traditional Unionist Voice party, a break away from the DUP.

The results show that a section of middle class Protestant voters rejected unionism in whatever form and voted for the Alliance Party, which claims to stand above the conflict over the partition of Ireland.

Under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement the main nationalist and unionist parties are obliged to enter into a power sharing administration. From 1998 until now Sinn Féin has taken the deputy First Minister’s post under David Trimble, the Unionist Party’s chief from 1998 until 2002 and then under various DUP leaders from 2007 onwards.

But faced with Sinn Féin becoming the largest party the DUP have reacted like a wee child whose losing the game: the DUP look set to try and walk away taking the ball with them. The party leadership says it will not enter a power sharing administration under Sinn Féin’s Michelle O’Neill (formerly Deputy First Minister now set to take the top job) unless the post-Brexit protocol concerning trade between Northern Ireland and the UK is thoroughly overhauled.

It remains unclear as to whether the DUP would serve in an Executive where it held the Deputy First Minister post.

Boris Johnson came to a DUP conference to pledge there would be no border in the Irish Sea separating the six county state from Britain but then agreed to exactly that with the EU and the Republic.

The DUP campaigned for Brexit during the referendum but Northern Ireland voted convincingly to remain in the EU. The DUP acts by simply ignoring that stubborn little fact. Under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement there cannot be a hard border between the Republic and Northern Ireland but that is exactly what the DUP yearns for.

During the election Sinn Féin’s campaign focused more on the cost of living crisis than achieving Irish unity as it looked to win nationalist voters who had never identified with the Republicans, and especially with the IRA’s military campaign of 1971 to 1997.

There is a difference how it positions itself in Northern Ireland, where it also focuses on its record for ‘responsible’ government, with that in the Irish Republic where it veers left, focusing on the appalling housing situation, low wages and other social issues. There it is the largest single party but was kept from office when the two traditional ruling parties, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael, traditionally at daggers drawn, joined with the Greens in a coalition to keep Sinn Féin out of government.

Since then Sinn Féin has grown stronger in the Republic.

Since partition whoever is in government in Dublin has simply turned their backs on what goes on in Northern Ireland and whatever their rhetoric has had no interest in uniting Ireland, creating instead a pro-business 26 county state beloved by both the European Union and the United States.

Under the terms of the Good Friday Agreement an all-Ireland referendum can be held on Irish unity if both governments agree to it. Support for Irish unity has risen in the Republic but at present there is no guarantee it would win a majority, a pro-unity majority is required in both states.

Sinn Féin in pushing for unity in the south has downplayed economic and social issues but that leaves major questions unanswered. For instance, the National Health Service operates in Northern Ireland but health provision in the Republic relies in part still on the Catholic Church and leaves much to be desired.

Extending the NHS across all of Ireland would be a popular measure but the cost is not something Irish business is prepared to see met.

As socialists we champion Irish unity because the Northern Ireland state was the creation of British imperialism and partition prevented the Irish people from exercising the right to self-determination – in an all-Ireland election in 1918 the majority of people in Ireland voted for Sinn Féin which stood on a clear platform of creating an all-Ireland Republic.

We want to see a united Irish working class but to achieve that means challenging the legacy of partition which created a vicious sectarian state run by the unionists. That legacy has to be challenged and overcome to establish genuine, lasting unity.

For decades the unionists in Belfast pointed south to a poorer state with high unemployment, high emigration and dreadful social services. Today the Republic has outstripped Northern Ireland in terms of living standards and infrastructure like roads and highspeed railways.

The fact is that Northern Ireland is now marked by lower wages and higher poverty levels.

Another change is that the Republic was governed in turns by two pro-business parties, Fianna Fail and Fine Gael. Compared to elsewhere in Europe the left was marginal. Today, alongside the success of Sinn Féin we have seen the emergence of People Before Profit with, currently, five members of the Irish Parliament. It organises on both sides of the border and before this week’s election had one Assembly Member. Despite the pressure in the West Belfast seat to vote Sinn Féin, it was welcome that Gerry Carroll kept his seat there. It’s vital socialists in the British state build close links with People Before Profit.

Sinn Féin’s success is to be welcomed. The party’s president Mary Lou McDonald has said they will push for an all-Ireland referendum within five years. That is to be welcomed and its a timetable that should be kept to, if they can get elected to government in the Republic.

Within Northern Ireland the fear is that Sinn Féin will not present a radical face as the leadership of Northern Ireland government, if one is formed. If Protestant workers are to be broken from unionism then a radical approach is the only way to do it. They feel alienated from their traditional middle class unionist leaders but without a radical pole of attraction that can mean a drift to apathy or, worse, sectarianism.

Back in Britain while everyone pretends they are cool with Sinn Féin topping the poll the reality is a bit different.

Boris Johnson is caught over Brexit, of which he is an architect, and his promises to the DUP which he broke. In the US President Biden has made it clear the Good Friday Agreement must be adhered to the letter giving Johnson little wriggle room.

Labour, under Sir Keir Starmer, has said little about the future of Northern Ireland and it’s hard to see Starmer building links with Sinn Féin.

In Wales Plaid Cymru has done exactly that, to their credit, but the ruling party in Scotland, the Scottish National Party, has avoided any contact with Sinn Féin. Nicola Sturgeon has said Sinn Féin’s success raises ‘big questions’ around the future of the UK state. Correct. Perhaps she should invite Michelle O’Neill to Edinburgh to discuss it.

If a campaign gathers pace for Irish unity then socialists in England, Wales and Scotland should throw their weight behind it.

Meanwhile, savour the result. And think of Sir Edward Carson, Sir James Craig and Sir Basil Brooke spinning ever faster in their graves as a pro-Irish unity party wins in a sectarian state they created in the believe that could never happen.[i]

[i] Sir Edward Carson led the Unionists campaign against Irish Home Rule in 1910-1914 helping arm the Ulster Volunteer Force with German weapons. Sir James Craig became the first prime minister of Northern Ireland serving until 1940. In 1934 he boasted, “we are a Protestant state for a Protestant People.” Sir Basil Brooke was prime minister from 1943 to 1963. In 1933 he told an Orange Order rally, “If we in Ulster allow Roman Catholics to work on our farms we are traitors to Ulster… I would appeal to loyalists, therefore, wherever possible, to employ good Protestant lads and lassies.”

Join Revolution! May Day weekender in London

The world is changing fast. From tariffs and trade wars to the continuing genocide in Gaza to Starmer’s austerity 2.0.

Revolution! on Saturday 3 – Sunday 4 May brings together leading activists and authors to discuss the key questions of the moment and chart a strategy for the left.