Chris Bambery examines the challenges posed and opportunites presented by contemporary workplace organising

The reality of work and day to day exploitation, and how to organise against it, is something which should be at the heart of Marxism. It was ever in the thoughts of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, while Lenin and Trotsky took this forward in analysing the battle ground that was industrialising Russia. Antonio Gramsci was fascinated by newly industrialised Turin and the burgeoning workers movement there. Closer to home, Tony Cliff examined the rise and fall of British working class insurgency in the 1960s and 1970s.

Yet in the decades since the ebbing away of the post-1968 rebellion in the Western capitalist world there has been little attempt by Western European and North American Marxists to examine the changes which have taken place, despite a relentless neoliberal drive which has led to major changes in the daily reality of work.

The neoliberal workplace

The most obvious change is that work dominates our lives even more than was the case thirty years ago. All the statistics show mounting hours of overtime, both paid and unpaid. In recent weeks I’ve taken the opportunity to talk to people I know about their experiences of work. I’m by no means presenting this as a scientific survey, but it does raise anecdotally several issues that we need to address if we are to organise effectively in workplaces.

Let’s start with the sheer grind as described by one worker:

“Work is hard, it’s long hours and you are under pressure to work extra unpaid. Everyone is on rolling three month contracts and feel under pressure to perform in order to keep their jobs. In addition we’ve unpaid interns and that puts extra pressure on you because you feel the company might replace you with one!”

New management techniques

The proliferation of managers – many of whom are often managers in name only – increases surveillance, attempts to bind people to the company and creates obstacles to collective organisation. Added to that is a blurring between management and the workforce. One older worker points to some differences in his time at work:

“When I first stated working there was a massive gulf between the shopfloor and management with a few foremen trying to bridge it (they were all men). Today that gap has narrowed. There is a major effort to get us to accept that we’re all in it together and to feel guilty about leaving on time or not working weekends.”

The same man noted that now there is a concerted attempt to build a corporate identity, or team spirit, as opposed to a collective one, and while there are clear limits to that – the reality of exploitation will assert itself – it is another pernicious influence given the lack of any tradition of collective action. He also points out staff are encouraged to negotiate their own wage rates and to keep these confidential. Lack of collective wage negotiation mean wage differentials, with no tradition of collectively to demand a pay rise for all.

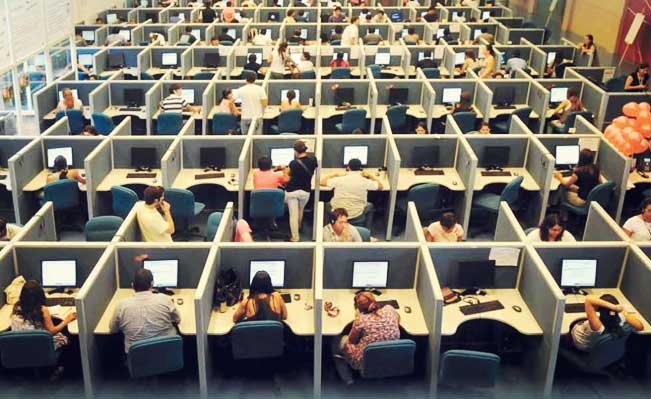

Space is an issue. Space in which workers can discuss, and organise, free from management observation is at a premium. Gone are tea breaks and a workplace canteen. The result is increased fragmentation, as this worker notes:

“There is literally nowhere to have a chat. If you get up and wander over to someone’s desk a manager will notice and after a few minutes inquire what you are doing. Usually that’s done in a pleasant way but I’ve seen a senior manager bawl people out in front of the whole office. Open plan offices seem democratic but they mean you are under constant observation.”

Several people point to examples of what can only be described as bullying and that is a growing issue of concern – and a potential issue from which union organisation could begin.

They hated the war, but they’re not in the union!

But organising a union is much more difficult. In one workplace an attempt to win union recognition failed because it was reported:

“The company went through the list of union members and pointed out they were technically employed by different companies (all of course subsidiaries) and simply dismissed it out of hand. We have, however, got management to meet with a union official which we feel is a result.”

Another worker points out:

“Talking to colleagues most of them have had some involvement in political activity in recent years, even if they don’t describe themselves as political. That ranges from marching against the Iraq war to visiting Occupy to signing a petition over a deportation, but they don’t seem to make any connection between that and being in a union, even those who are union members!”

I asked the person who was involved in organising at work what arguments they used to recruit to the union:

“To be honest I don’t make a big pitch about the need for solidarity and the idea of industrial action doesn’t get a mention. The cutting edge argument is that the union provides legal support. I also mention that unionised workplaces enjoy better rates of pay. It’s a bit depressing but that’s where we are. One good thing is that the union is involved in some good issues, Palestine for instance, and I can use that to get people a bit more involved and even interested.”

Talking to the one person who is a union rep I was struck by how far the way that they operate is from the shop stewards of the 1970s. Union work is done furtively with no time off for union business or meetings and usually union work involves giving advice regarding individual grievances. Interestingly one issue concerning conditions came up affecting everyone, union membership increased and people felt they scored a modest result.

New challenges, new opportunities

This is a snap shot of different people’s experiences. None of the difficulties mean we cannot organise at work nor does it negate the reality of exploitation which, as Marx points out, necessarily creates class struggle of one sort or another. But he also pointed out capitalism is wonderful in the ways that, having brought workers together, it then divides them.

It also suggests we cannot just keep on waiting for a strike wave to occur which will sort everything out. We’ve been waiting now for three decades. The situation we are in is I believe unprecedented in that we have been through a protracted economic crisis preceded by a long period of relatively low levels of workplace struggle. The effects of that have to factor into any analysis of class consciousness and class organisation.

The neoliberal offensive which began all those years ago continues and the recession which began in 2008 gave new opportunities for corporate management. Recognising that work itself is harder than three decades ago does not mean class struggle is negated – it just means facing reality which then allows you to work out new strategies. The bright spot is the sheer number of people in any workplace who’ve taken part in some form of protest. That provides a good starting point for getting things moving.