Lindsey German reviews two case studies of the Nazi period, which, from above and from below, reveal the class nature of the regime and the resistance to it

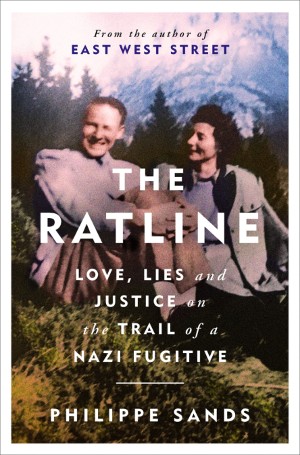

Even those who know some of this history will be fascinated by these books. You may know, for instance, of the Nazi gauleiters that presided over the horrors of brutal repression or of the events leading up to the Holocaust. Or the fact that many Nazi war criminals escaped justice, going into hiding and protected by friends and family, or fleeing to Latin America after the war with the help of powerful allies, not least in the Vatican in Rome. Philippe Sands’ book tells the story of one such war criminal, but in such an exceptional and detailed way that it is as though you are becoming aware of it for the first time. A well-known international lawyer, he has written previously of his family’s fate in the Holocaust, and puts a huge amount into his research.

His focus is Otto Freiherr von Waechter, SS Brigadefuehrer and governor of Galicia (then part of occupied Poland) during the war. Sands has a particular interest given that Waechter presided over the murder of many Jews and Poles in the area, including members of his own family, who lived in the area round Lviv (Lvov in Russian and Lemberg in German). Waechter came from a well off and conservative family, and grew up against a background of imperialist war in the dog days of the Austro-Hungarian empire. His father was awarded the right to call himself freiherr (baron) and Otto was also able to use the title and add the aristocratic ‘von’ to their surname. As a young law student in Vienna he participated in anti-Semitic demonstrations and joined the Austrian Nazi Party in 1923.

The stage was set for a long career of Nazism and Otto did not disappoint. He was buoyed by Hitler’s victory in Germany in 1933, was involved in the coup against the Austrian Chancellor Dollfuss, who was shot in July 1934, and then fled to Germany and worked for the SS. Chances of advance came in 1938 with the Anschluss where Hitler annexed Austria and Waechter rose to further prominence. By this time he was married to Charlotte, who was equally reactionary.

Wealth and genocide

One of the key assets of Sands’ book is that he has access to Charlotte’s diaries. There is much talk of the ‘banality of evil’ in relation to fascism and here we have evidence of exactly that. She recounts their move into a huge house following the Anschluss and how an architect friend ‘obtained the Jewess Bettina Mendl’s house for us’ (p.68). In 1941, with Otto now governor of Krakow and organising to expel Jews from the city and create a ghetto for those who remained, Charlotte sends a letter with diagram urging him to build a fitted wardrobe for her clothes in their new house (p.81). After a visit to the Warsaw ghetto she goes shopping for shoes and then to a concert in the evening (p.83).

Just after the Wannsee conference in 1942, which led directly to the ‘final solution’, Otto was appointed governor of Galicia and moved to Lemberg, where again he presided over deportations, executions and repression of Jews. Charlotte meanwhile encouraged her twelve-year-old to visit, describing their house with a big garden, tennis courts and swimming pool, and a pony. In August that year die Grosse Aktion led to tens of thousands of Jews in the city rounded up and sent to an extermination camp (pp.94-5).

However, this was the year the war turned and following Germany’s defeat at Stalingrad the Red Army advanced slowly towards Vienna and Berlin. Flight from Lemberg followed, and after the war Otto, ever the loyal Nazi, went into hiding. His wife lived in the family farmhouse in western Austria, now under the control of the Americans, who requisitioned the property but soon restored it to her and treated her very well. To avoid capture, Otto hid in the mountains for three years, well provided for by his wife.

Power facilitated escape

As Sands says, however, he was not alone. While men like Waechter were hunted by a number of agencies, including Jewish ones, these were often not successful. A network of Nazis and their allies organised the escape of war criminals especially through the Ratline from Salzburg, the Tirol and northern Italy to Rome, where they escaped with new identities to Latin America. Here Otto, hiding in a monastery and aided by highly placed figures in the Vatican, died in 1949. The story has some interesting twists: was he murdered by a former ‘comrade’ to stop him talking?

Otto and Charlotte’s fourth child, Horst, cooperated at least partly in the research.

Sands’ fraught relationship with him is told well. Horst recognises more than most of his family about his father’s role, but he cannot see him as a war criminal and remains very close to his mother until her death in 1985; ‘a Nazi until the day she died’, as Horst’s Swedish wife told Sands.

This is a gripping and engaging book which tells one man’s story but in the process tells us also about the suffering of Sands’ Jewish relatives in Galicia, the nature of the Nazi infrastructure and the ruthlessness with which it operated, the class polarisation in Germany and Austria, which created widespread support for fascism among the wealthier sections of society. It also demonstrates how powerful forces under capitalism were able to ignore or sometimes facilitate the escape from justice of so many.

Class resistance

There were, however, many good Germans (and Austrians) who helped those in danger from the Nazis and resisted Hitler. Catrine Clay’s book tells the story of some of them. Particularly good is the treatment of Irma Thaelmann, the teenage daughter of Communist leader Ernst Thaelmann, who was imprisoned soon after Hitler came to power and executed eleven years later in August 1944. Her stories of resistance are heroic, as are those of Bernt Engelmann, who as a schoolboy from a Social Democratic family worked with a resistance group organised by Tante (aunt) Ney in a local Dusseldorf bakery. Clay points out that resistance included Communists, Socialists, Quakers, Catholics and other religious groups, factory workers and Prussian officers. Punishment when caught was draconian.

The usual narrative all too often stops at the plots against Hitler from within the officer class of the military, especially the failed July bombing in 1944 for which there were savage reprisals. The left-wing opposition is ignored but it was real and endured very late into the regime despite the smashing of left-wing party infrastructure by the middle of 1933. More than sixty Hamburg shipyard workers in an underground group were arrested and sentenced to death in late 1942. The Herbert Baum group in a Berlin Siemens factory set fire to an anti-Soviet exhibition. Despite being dragged round the factory after arrest and torture, Baum refused to identify accomplices. Clay gives us many other examples.

The book has faults – she was a BBC producer, and it at times reads like the accompaniment to a series. But it contains a lot of information which is not widely available elsewhere (at least in English) so is worth a read. Both writers talk about the midnight of the twentieth century, when societies were run by people like Waechter. We should remember – and in different ways this is highlighted in both books – that capital turns to fascism in periods of extreme crisis, and that it has to smash the working-class movement, as it did in Germany in 1933, in order to succeed. The French Marxist Daniel Guérin argued that fascism is the price the working class pays for not having made the revolution. And these working-class people paid a very high price.

Join Revolution! May Day weekender in London

The world is changing fast. From tariffs and trade wars to the continuing genocide in Gaza to Starmer’s austerity 2.0.

Revolution! on Saturday 3 – Sunday 4 May brings together leading activists and authors to discuss the key questions of the moment and chart a strategy for the left.