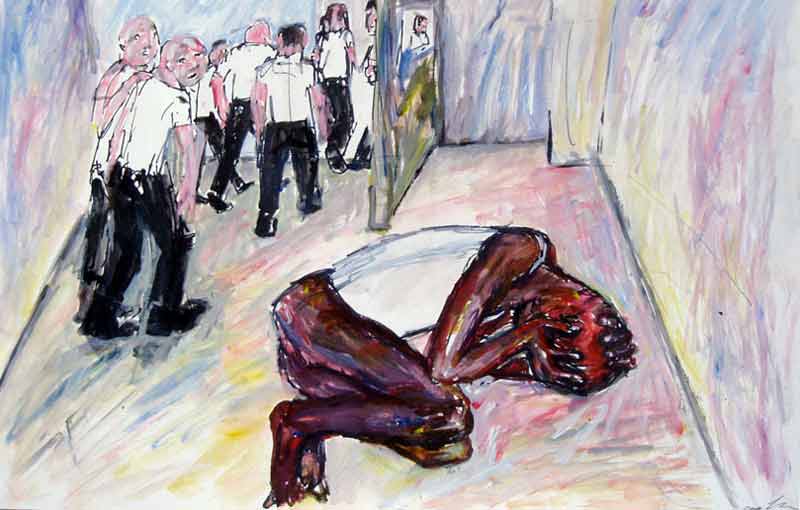

Painting by Lucy Edkins from Mental Health in Immigration Detention Action Group Initial Report December 2013

Painting by Lucy Edkins from Mental Health in Immigration Detention Action Group Initial Report December 2013

Four years ago G4S was involved in the unlawful killing of an immigration detainee called Jimmy Mubenga. Now they’re winning NHS contracts to provide medical care for immigration detainees

NHS England has awarded security giant G4S a series of multi-million pound contracts to run medical facilities at four detention centres where men, women and children are held pending deportation.

The seven-year contracts, worth £23.4 million, became operational last month. G4S has taken over healthcare services at Yarl’s Wood Immigration Removal Centre in Bedfordshire, previously provided by outsourcing rival Serco.

The change comes in the wake of a sexual abuse scandal at Yarl’s Wood, where one male Serco nurse reportedly told a female detainee who complained of headaches that “she did not need medication but needed his penis”.

Is G4S any more fit to give medical care to vulnerable detainees?

The company is best known among asylum seekers for its involvement in the death of Jimmy Mubenga, the 46 year old father of five who died after heavy restraint by three G4S guards on a British Airways plane four years ago today. Last year an inquest jury found that Mubenga had been unlawfully killed.

Jimmy Mubenga and child

The three other new contracts handed to G4S by NHS England cover medical duties at Brook House and Tinsley House detention centres outside Gatwick Airport and the detention facility called Cedars in the village of Pease Pottage where families with young children are detained.

Healthcare on the detention estate has until recently been commissioned by the Home Office. Successive governments have insisted that standards matched those within the NHS. But the evidence tells a different story.

The Children’s Commissioner for England reported in 2010 that Serco nurses examining children held at Yarl’s Wood routinely described their emotional state as “jolly” and “happy”. About one Yarl’s Wood child whose mother had been raped in Africa and was hepatitis B positive, Serco nurses wrote under family history, “nil of note”. (PDF here)

The Prisons Inspectorate reporting on Harmondsworth Immigration Removal Centre two years ago found that medical reports relating to detainees who had experienced torture or were unfit to detain “were of poor quality, often providing no clinical judgement”.

In another shocking report on Harmondsworth in January this year Prison Inspectors revealed that a frail and demented 84 year old man was kept in handcuffs for five hours before his death.

This past June the inquest into the death in Colnbrook Immigration Removal Centre of American tourist Brian Dalrymple heard that a 77 year old locum doctor who had responsibility for him knew neither mental health law nor detention centre rules.

The jury found: “Throughout Mr Dalrymple’s detention at Harmondsworth medical record keeping was shambolic.” Private health contractors Nestor Primecare Services Limited, The Practice PLC, the locum doctor and the GEO Group agreed a “significant” financial settlement” with Dalrymple’s mother.

After years of criticism by the Prisons Inspectorate, the Royal Medical Colleges, the courts, medical charities, MPs and Peers, and rising demands that commissioning should be done by the NHS, responsibility for healthcare commissioning was at last transferred to NHS England in April last year. This raised hopes among medical professionals that improvements would follow.

Looking forward to the change, Professor Hilary Pickles and Dr Naomi Hartree wrote in the British Medical Journal in March last year:

“This change could improve services for a vulnerable group of patients. Until now, healthcare provision for those detained under the Immigration Act has mostly been provided by private companies contracted to the UK Border Agency—in effect, a backwater of publicly funded healthcare that many would describe as failing.”

But hopes for improvement seem misplaced if NHS England hands contracts to companies with a reputation for damage and dishonesty. G4S and Serco are under criminal investigation by the Serious Fraud Office for heavily overcharging the taxpayer on electronic monitoring contracts.

G4S provides medical services at Morton Hall Immigration Removal Centre in Lincolnshire, where Rubel Ahmed, a 26-year-old male detainee from Bangladesh, died on 5 September 2014. Witnesses interviewed by Corporate Watch say Rubel Ahmed repeatedly called for medical assistance an hour before his death, but doctors did not attend his cell until after he had died. The Home Office told the Ahmed family that the cause of death was suicide. The Prisons and Probation Ombudsman is investigating.

In June this year the South Staffordshire coroner ruled that prisoner Steve Ham’s death was caused by heart disease and the “sub-optimal care” he had received from G4S staff at HMP Oakwood, privatisation’s flagship prison. For almost an hour after Ham was found unresponsive, G4S guards failed to call an ambulance.

Besides the doubts over private contractors’ competency to treat vulnerable detainees, there are other concerns.

Over to Dr Charmian Goldwyn, a retired general practitioner who wrote this letter to the British Medical Journal in April last year:

“I welcome the transfer of healthcare from the UK Border Agency to the NHS in immigration removal centres. I am a retired GP and have been visiting such centres as a volunteer doctor for the past six years. I have been involved with more than 370 asylum seekers, 306 of them in immigration removal centres, and at least 180 of these detainees had medical problems that were not being properly dealt with by the healthcare centres.

Many of the detainees tell me that the medical staff do not believe them when they consult with serious symptoms. Examples include, headaches in someone later admitted with meningitis; haemoptysis in a patient previously diagnosed with tuberculosis; and blood pressure, asthma, and diabetes out of control. Some detainees fear that the medical staff are ‘in league’ with the UK Border Agency and determined to pronounce them ‘fit to fly’, despite being very sick or in the middle of treatment.

Asylum seekers who have been tortured in their home country are so terrified of return that they seriously self harm—cutting themselves, attempting suicide, refusing food. They have limited access to psychiatric help despite such profound despair.

The medical care of these extremely vulnerable people deserves to be a specialty on its own, with healthcare providers receiving specialist training on these patients’ medical and psychological needs.

However, it would be infinitely better if these people were not imprisoned in the first place, especially as many are eventually released back into the community. A study by South Bank University, London, [PDF here] concluded that at most 8-9 per cent of asylum seekers who get bail (after being released from an immigration removal centre) subsequently attempted to evade the asylum system. It seems extreme to incarcerate people who are very sick, have mental health problems, or are in wheelchairs.”