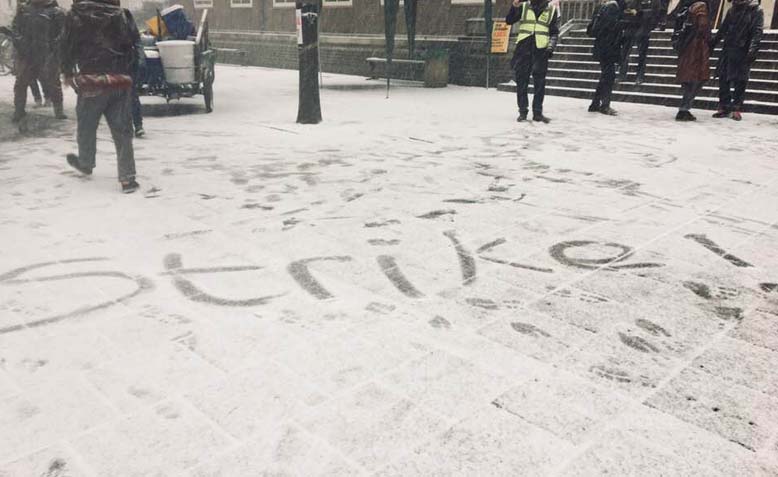

Lecturers get creative on the SOAS picket line. Photo: Feyzi Ismail

Lecturers get creative on the SOAS picket line. Photo: Feyzi Ismail

University staff and students have shown that committed and passionate resistance is possible and neccesary, finds Des Freedman

As tens of thousands of university staff enter their fourth (and potentially final) week of strike action against pension cuts, it feels like campuses are in the middle of a big transformation. At the start of the year, the university experience was summed up by demoralised staff, stressed and indebted students, overpaid senior managers and a system geared towards rankings and surpluses rather than knowledge and learning. That has changed drastically after nine days of picket lines, teach-outs, rallies, debates, screenings and a different kind of education than the one that’s confined to lecture theatres and seminar rooms.

The strikes started in winter but are finishing in spring.

At Goldsmiths where I work, the vast majority of teaching has been disrupted and there’s a real determination amongst strikers not to back down until we secure our existing ‘defined benefits’ (DB) pensions. We have organised teach-out activities for pretty much every day but then there are also lots of spontaneous events: an exorcism (of the market from the College), picket line poetry, live music and visits from a whole range of political and community groups.

All the reports I’ve heard from around the country tell the same story: of a huge growth in UCU membership, of the biggest and liveliest pickets anyone can remember, of a belief that we can actually win and, most significantly, of a desire to speak about more than pensions. Supported by students who are, after all, the innocent victims of a crisis generated by the desire of a minority of vice-chancellors to remove what they see are the ‘liabilities’ of the DB scheme, much of the talk on the picket line is about what kind of university we want, about whether we should elect senior management, about who should control resources and where should they be directed. Questions about governance that used to induce yawns from most people now take on a far more radical edge as they relate to the issue of who should have power in the contemporary university.

This is what can happen with strike action: it gives us a glimpse of our own power, raises our expectations and shows us things we didn’t expect. Who would have thought, three weeks ago, that a strike organised around heavily technical debates concerning the Universities Superannuation Scheme would have generated this level of militancy and helped to reignite a student movement that has lain relatively dormant since the 2010 tuition fee campaign? Who would have thought that both students and staff have become lay experts in the mechanics of pension schemes and ‘technical provisions’?

We don’t know what will happen in the next few months. It’s entirely possible that the employers, already heavily divided between those who want to weaken the union and those who are desperate to secure a return to work, will make an offer this week. It’s also entirely possible that they will attempt to hold their nerve in the belief that ours will weaken and that it will be harder to retain the strength and unity we have shown so far.

The union has now sanctioned further strike action to hit the exam period after the Easter holidays if the dispute is not resolved by then. Whatever happens, the UCU strikes have demonstrated that even the most demoralised sector can recover its spirit in the course of taking action. We saw this lesson with the junior doctors in 2016 and cinema workers fighting against low pay in 2017.

But of course, it matters what the eventual outcome is. If we are forced back to work or we settle for less, then so much of what we have gained will be frittered away. If we are able to maintain our determination to win – and make no mistake, we are very determined to win, as more and more of us simply do not believe that there is a deficit in our pension scheme – then we will be in a far better position to address the other issues that mark life in the neoliberal university: the terrible precarity facing academics, the outsourcing of so many services, the emerging crisis of mental health on our campuses, the enormous cost of housing, gender pay gaps and the attainment gap affecting BAME students. And that’s not even mentioning the whole debate over tuition fees and the need for decent grants so that people from disadvantaged backgrounds can study with dreading the thought of facing a ‘lifetime of payments’ as the former Universities minister, David Willetts, once called debt.

So I hope that campuses up and down the country keep up the teach-outs and the pickets and maintain the solidarity with students. We shouldn’t take student support for granted – we need patiently to debate with students that success in this dispute will weaken the market logic that has forced up the costs of their education and commodified the whole university experience.

Another vital thing is to start developing solidarity from other workers in both the public and private sector who might take inspiration from the resolve of UCU members and apply it to their own workplaces and industries in the continuing struggle against austerity. I think we need to start getting in touch with local union branches, trades Councils and Labour Party groups and so on and say can we come and talk to you? We need your support. Even simple things like getting sympathisers to post pictures with them holding signs saying we support the lecturers

But above all, we should take heart from the fact that, through nine days of strike action with more to come, university staff and students have shown that committed and passionate resistance is possible, necessary and – if you believe the opinion polls – actually popular. The UCU action has split the employers, galvanised students, generated some sympathetic headlines and put strikes very much back on the map.