New Model Army. Photo: masterengrev.wordpress.com

New Model Army. Photo: masterengrev.wordpress.com

The Diggers had several songs, but their most renowned one was never published in their time. Today, only one anonymous, untitled, and undated version of the song exists, writes Ariel Hessayon

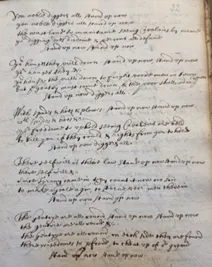

The Diggers had a handful of songs, although the most famous remained unprinted during their day. Only one version of this well-known song is extant, however, and it is anonymous, untitled and undated. It is preserved in the papers of the military administrator Sir William Clarke (1623/24–1666), who had served as an assistant secretary and then secretary to the council of officers of the New Model Army.

When the song was written down – most likely in March, April or May 1650 – Clarke was living in London and acting as a senior secretary to Sir Thomas Fairfax (1612–1671), commander-in-chief of Parliament’s forces in England and Ireland.¹ The version that we have is in Clarke’s handwriting. Since Clarke had previously transcribed several documents relating to the Diggers, including letters and papers addressed to Fairfax, it is unsurprising that he also copied this song. Most likely Clarke or Fairfax (who resigned his commission in summer 1650) had an interest in the movement.

The first scholar to notice the Diggers’ song was Sir Charles Harding Firth (1857–1936), who would be appointed Regius Professor of History at the University of Oxford in 1904. Firth included it in the second volume of his selections from The Clarke Papers published by the Camden Society in 1894.

Besides entitling it The Diggers Song, Firth’s published version contains several editorial amendments: spelling has sometimes been modernised, as has capitalisation; punctuation has occasionally been supplied; contractions have been expanded; a transcription error silently corrected; line breaks inserted to retain the rhyme; and words added where the original merely indicates repetition through the use of ‘&c.’

Thereafter Firth’s published version of this song was reprinted in whole or in part by, among others, Eduard Bernstein, a German political figure and friend of Friedrich Engels then exiled in London (1895); the Scottish Unitarian, republican and journalist John Morrison Davidson (1899, 1904); the land reformer Lewis Berens (1906); the Christian socialist Joseph Clayton (1910); the Reverend E.A. White (1940), a committee member of the English Folk Dance and Song Society; George Sabine, a professor of philosophy who would become Vice President of Cornell University (1941); the Marxist historian Christopher Hill and Edmund Dell, a future Labour MP and minister (1949); the Australian-born writer Jack Lindsay (1954); Hill again, then Master of Balliol College, Oxford (1973); the folklorist Roy Palmer (1979); the Socialist politician Fenner Brockway (1980); Andrew Hopton (1989); Alastair Fowler (1991); H.R. Woudhuysen (1992); Peter Davidson (1998); Stephen Duncombe (2002); and Carolyn Forché and Duncan Wu (2014).

All the same, it appears that not one of these people consulted the original manuscript – even after it was available in microfilm.² Indeed, Berens and Hill modernised the spelling found in Firth, presumably to make the text more accessible, while Sabine carelessly omitted the final verse.

Here I present a transcription of the original manuscript, supplying line breaks so as to respect the original rhyme:

You noble diggers all stand up now

you noble diggers all stand up now

the wast land to maintaine seeing Cavaleirs by name

yor digging does disdaine & persons all defame

Stand up now stand up nowYor houses they pull down: stand up now, stand up now

yor houses they &c.

yor houses the[y] pull down to fright poore men in town

but ye Gentry must come down, & the poor shall wear ye crown

Stand up now diggers all.With spades & hoes & plowes: stand up now stand up now

wth spades & hoes &c.

yor freedome to uphold seeing Cavaleirs are bold

to kill you if they could & rights from you to hold

Stand up now diggers all.There selfwill is theire law, stand up now stand up now

there selfwill &c.

Since Tyranny came in, they count it now no sin

to make a Gaole agin,³ to sterue⁴ poor men therein

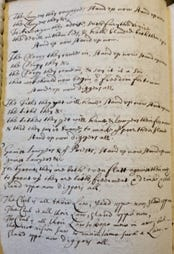

Stand up now stand up nowThe Gentrye are all round, stand up now stand up now

the gentrie are all round &c.

the Gentrye are all round on each side they are found

there wisedomes so profound, to cheat us of or ground

Stand up now stand up now.The Lawyers they conjoyne, stand up now stand up now

the lawyers they &c.

To Arrest you they advise, such fury the[y] devise

the devill in them lies, & hath blinded both their eyes

Stand up now stand up now.The Clergy they come in, stand up now stand up now

the Clergy they &c.

the Clergy they come in, & say it is a sin

that wee should now begin, or freedom for to win

Stand up now diggers allThe Tiths they yet will haue, stand up now stand up now

the tiths they &c.

the tithes they yet will haue, & Lawyers their fees crave,

& this they say is braue, to make ye poor their slaue

Stand up now diggers all.’Gainst Lawyers & ye Priests, stand up now stand up now

’gainst Lawyers &c.

for Tyrants they are both, even flatt against their oath

to grant us they are loth, free meat & drinke & cloth

Stand uppe now diggers all.The Club is all their Law, stand uppe now, stand up now

The Club is all their Law, stand uppe now,

The Club is all their Law to keepe men in awe,

but they noe vision saw to maintaine such a Law.

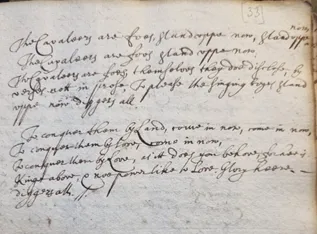

Stand uppe now diggers all.The Cavaleers are foes, stand uppe now, stand uppe now,

The Cavaleers are foes stand up now

The Cavaleers are foes, themselves they do disclose,

by verses nott in prose, To please the singing boyes

Stand uppe now diggers all.To conquer them by Land,⁵ come in now, come in now,

To conquer them by Love, come in now,

To conquer them by Love, as itt does you behove,

for hee is King above, & noe power like to Love.

Glory heere diggers all.

Firth suggested that the Digger leader Gerrard Winstanley (1609–1676) probably wrote this song. He did so because verses are found in several of Winstanley’s printed works. Hence the title-page of Winstanley’s A Watch-Word to The City of London, and the Armie (September 1649) has:

When these clay-bodies are in grave, and children stand in place,

This shewes we stood for truth and peace, and freedom in our daies;

And true born sons we shall appear of England that’s our mother,

No Priests nor Lawyers wiles t’imbrace, their slavery wee’l discover.

Again, on pages fifteen and sixteen we find:

The work of digging still goes on, and stops not for a rest:

The Cowes were gone, but are return’d, and we are all at rest.

No money’s paid, nor never shall, to Lawyer or his man

To plead our cause, for therein wee’ll do the best we can.

In Cobham on the little Heath our digging there goes on.

And all our friends they live in love, as if they were but one.

Similarly, the title-page of Winstanley’s The Law of Freedom in a Platform: Or, True Magistracy Restored (1652) has:

In thee, O England, is the Law arising up to shine,

If thou receive and practise it, the crown it wil be thine.

If thou reject, and stil remain a froward Son to be,

Another Land wil it receive, and take the crown from thee.

Again, in the second chapter, we find:

The Winter’s past, the Spring time now appears,

Be gone thou Kingly Tyrant, with all thy Cavaliers.

The day is past, and sure thou dost appear

To be the bond-mans son, and not the free-born Heir.

Then at the conclusion of the book we have:

Here is the righteous Law, Man, wilt thou it maintain?

It may be, is, as hath still, in the world been slain.

Truth appears in Light, Falshood rules in Power;

To see these things to be, is cause of grief each hour.

Knowledg, why didst thou come, to wound, and not to cure?

I sent not for thee, thou didst me inlure.

Where knowledge does increase, there sorrows multiply,

To see the great deceit which in the World doth lie.

Man saying one thing now, unsaying it anon,

Breaking all’s Engagements, when deeds for him are done.

O power where art thou, that must mend things amiss?

Come change the heart of Man, and make him truth to kiss:

O death where art thou? wilt thou not tidings send?

I fear thee not, thou art my loving friend.

Come take this body, and scatter it in the Four,

That I may dwell in One, and rest in peace once more.

Clearly Winstanley may have penned what Firth called The Diggers Song. Yet there is another possibility. This was Robert Coster, whose name appears as a signatory to several Digger documents between December 1649 and April 1650.⁶ Sometimes referred to by modern scholars as the ‘Digger poet’, Coster was the author of A Mite Cast into the Common Treasury (December 1649). This eight-page pamphlet contains ten lines of verse signed by Coster, followed by eight stanzas each consisting of twelve lines. Here are the third and eighth stanzas:

The Poore long

have suffered wrong,

By the Gentry of this Nation,

The Clergy they

Have bore a great sway

By their base insultation.

But they shall

Lye levell with all

They have corrupted our Fountaine;

And then we shall see

Brave Community,

When Vallies lye levell with Mountaines.

The glorious State

which I do relate

Unspeakable comfort shall bring,

The Corne will be greene

And the Flowers seene

Our store-houses they will be fill’d

The Birds will rejoyce

with a merry voice

All things shall yield sweet increase

Then let us all sing

And joy in our King,

Which causeth all sorrowes to cease.

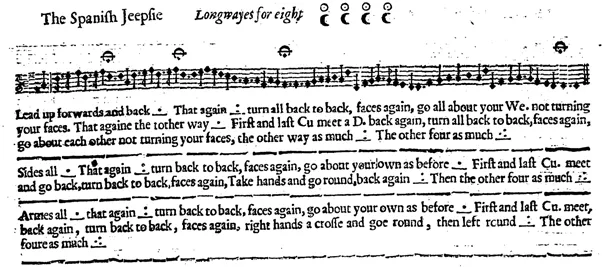

A further work, without indication of authorship, appeared about April 1650. This was entitled The Diggers Mirth, or, Certain Verses composed and fitted to Tunes, for the delight and recreation of all those who Dig, or own that Work, in the Commonwealth of England (1650). This sixteen-page pamphlet began with ‘The Diggers Christmas Carol’, a composition of twenty-five stanzas, each containing six lines, sung to the tune of ‘The Spanish Gypsy’. As E.A. White pointed out more than seventy-five years ago, ‘The Spanish Gypsy’ was included in The English Dancing Master: or, Plaine and easie Rules for the Dancing of Country Dances, a collection acquired by the London-based book collector George Thomason on 19 March 1651.

According to White, the words of ‘The Diggers Christmas Carol’ ‘exactly fit the tune’. Here are the first and twenty-fifth stanzas:

You people which be wise,

Will Freedom highly prise;

For experience you have

What ’tis to be a slave:

This have you been all your life long,

But chiefly since the Wars begun.

But Freedom is not wonn,

Neither by Sword nor Gunn:

Though we have eight years stay’d,

And have our Moneys pay’d:

Then Clubs and Diamonds cast away,

For Harts & Spades must win the day.

Lewis Berens thought that ‘The Diggers Christmas Carol’ was probably by Coster and I agree. It was followed by a further composition consisting of eighteen stanzas, each containing four lines. Here are the first and last stanzas:

A hint of that FREEDOM which

shall come,

When the Father shal Reign alone

in his Son.

The first that which this Stone shall smite,

shall be the head of Gold;

A mortal wound he shall them give

now minde thou hast been told.

Berens suggested that this second set of verses was penned by Winstanley rather than Coster. This is plausible, although they may have been written by Coster as well. What is certain is that both A Mite Cast into the Common Treasury and The Diggers Mirth were published while the Diggers were active on the Little Heath in Cobham, Surrey between roughly 24 August 1649 and 19 April 1650. Moreover, it seems to me that the Diggers’ song – which consists of twelve stanzas, each containing four lines together with a fifth shortened line – is stylistically closer to Coster’s compositions than Winstanley’s.

But regardless of whether the Diggers’ song was by Coster or Winstanley, it is possible to narrow down when it was written through examining its allusions. Thus the ‘wast land’ of the first stanza corresponds to the ‘Waste Land’ found on the title-pages of Winstanley’s A Declaration from the Poor oppressed People of England (c. May 1649) and An Appeal To the House of Commons (c. July 1649) as well as the ‘Waste and Common Land’ in A New-yeers Gift for the Parliament and Armie (c. December 1650). The second stanza bemoans the Diggers’ houses being pulled down, most likely referring to an event that happened on 28 November 1649.⁷

The ‘spades & hoes & plowes’ of the third stanza are similar both to the ‘spade and plow’ in A Letter to the Lord Fairfax (June 1649) and the ‘Spades and Howes’ in A New-yeers Gift. The fourth stanza’s ‘there selfwill is theire law’ resembles ‘their self-will and murdering Lawes’ in An Appeale to all Englishmen (26 March 1650). The sixth stanza relates how lawyers had been persuaded to prepare arrest warrants for the Diggers. This matches arrests that had been made in mid-October as well as, to quote John Gurney, ‘further prosecutions initiated in Kingston’s Court of Record in October, November and December’ 1649.

The tenth stanza’s ‘The Club is all their Law’ is mirrored in A New-yeers Gift, where Winstanley argues that if equity be denied ‘then there can be no Law, but Club-Law’. Elsewhere in the same tract there is condemnation of the ‘Lawyers trade’ as well as ‘Tithing Priests’ and the ‘Cavaleers cause’, not to mention the Lords of the manors who sent men to beat the Diggers and ‘pull down’ their houses. And just as the Diggers’ song concludes with a call to conquer their enemies by love, so Winstanley declares in his New-yeers Gift that ‘we will conquer by Love and Patience’.

All of this points to two possible dates of composition. Either the Diggers’ song was devised in December 1649; i.e. about the same time as ‘The Diggers Christmas Carol’ was written. Or it was composed around March 1650, at roughly the same time as the second poem in The Diggers Mirth. If the latter suggestion is correct then ‘stand up now’ from the chorus partially echoes ‘stand up for freedom’ in An Appeale to all Englishmen. But whatever the precise dating, Clarke most likely transcribed the song shortly before or just after the Digger community on the Little Heath in Cobham was destroyed on 19 April 1650.

Another challenging aspect of the song has been identifying the tune. Relying on the work of Miss A.G. Gilchrist, White suggested that the metre could be traced to a song mentioned in The Complaynt of Scotlande (1549). This contains the lines:

My lufe is lyand seik, send hym ioy, send hym ioy,

fayr luf lent thou me thy mantil ioy.

In all, White enumerated seventeen songs in this metre, stretching from the mid-sixteenth to the mid-eighteenth century. They included Captain Kidd (c.1701), ‘Oh my name is Captain Kidd, as I sailed, as I sailed’; and Admiral Benbow (c.1702), ‘Come all ye sailors bold, and draw near, and draw near’. Whether or not ‘Stand up now stand up now’ from the Diggers’ song can be connected with ‘Send him joy send him joy’, not to mention ‘as I sailed, as sailed’ as well as ‘and draw near, and draw near’, I leave to specialists to judge. But it has not been noticed that the twelve stanzas of the Diggers’ song may have had symbolic significance, alluding to the twelve tribes of Israel. For Winstanley had addressed his The New Law of Righteousnes ‘To The twelve Tribes of Israel that are circumcised in heart, and scattered through all the Nations of the Earth’ (26 January 1649).

Turning to the purpose of the Diggers’ song, it was likely to raise morale and instil a sense of community. Clearly it had a non-violent message, anticipating the Diggers’ ultimate triumph as they stood up to their assorted enemies – Cavaliers, gentry, lawyers and clergy – while brandishing their agricultural implements. Perhaps, as White proposed, it also functioned ‘as a labour song, to help them to break up their waste ground’.

Finally, the Diggers’ song has had an interesting legacy since Firth first published it. Consequently it was performed on 1 April 1939 (possibly on the 290th anniversary of the Digger movement’s foundation) as part of a three-day ‘Festival of Music for the People’ at a moment when there was international attention on the Spanish Civil War and Nazi Germany. Organised by the Popular Front (a group of left-leaning intellectuals and politicians), this festival opened at the Royal Albert Hall with a historical pageant spanning from ‘Feudal England’ to a finale ‘For Peace and Liberty’. The Diggers appeared in the fourth episode, ‘Soldiers of Freedom’, with music by Christian Darnton. Afterwards, the Diggers’ song featured in the 35mm black and white film Winstanley (1975). Directed on a limited budget by Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo, with a cast consisting almost entirely of amateurs, the film is notable for its historical details. There are also recordings of the Diggers’ song by Leon Rosselson and Roy Bailey (1979); Chumbawamba (1988); Attila The Stockbroker (1996); Lady Maisery (2016); Windborne (2017); and Farrell Family (2020).

1. The song is preceded by letters dated 16 March 1650 and 1 April 1650. It is followed by several letters written between 27 May and 4 June 1650.

2. White, however, did correspond with the librarian of Worcester College.

3. i.e. again. Hill, following Firth’s reading of ‘a gin’ interpreted gin to mean ‘trap’.

4. i.e. starve.

5. Presumably a transcription error for ‘Love’.

6. Someone named Robert Coster married Isabell Lenny at St Bartholomew the Less, London on 2 May 1653. Moreover, Andrew Coster, trunk maker of St Andrew Hubbard, London, bequeathed money to his ‘loving Brother Robert Coster’ in September 1658.

7. It should be noted, however, that a Digger house had previously been pulled down on St George’s Hill.

Join Revolution! May Day weekender in London

The world is changing fast. From tariffs and trade wars to the continuing genocide in Gaza to Starmer’s austerity 2.0.

Revolution! on Saturday 3 – Sunday 4 May brings together leading activists and authors to discuss the key questions of the moment and chart a strategy for the left.