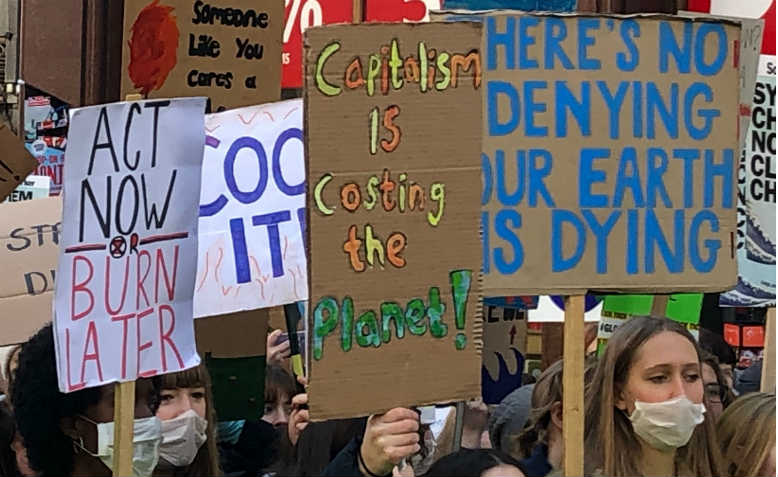

Climate Strike, November, London. Photo: Shabbir Lakha

Climate Strike, November, London. Photo: Shabbir Lakha

As part of a series of opinion pieces on the election result, Elaine Graham-Leigh argues that the movement must turn to class on climate

It was supposed to be the climate election. After a year of unprecedented prominence for the climate crisis as a result of the fantastic youth climate strikes and XR actions, this was supposed to be the moment when it would gain expression at the ballot box. In the end, of course, it didn’t work out quite like that. Despite the televised climate debate, policies on climate change were hardly an issue in the campaign; so much so that Johnson felt, correctly, that he was safe in not bothering to turn up to debate about them. The Green Party increased their overall vote share by 1.1%, but didn’t make any electoral breakthroughs. In Stroud and the Isle of Wight, where they were talked up as the main challengers to the Tories, they came a distant third. We now have a Tory government with a stonking majority and no serious commitment to anything like a credible policy for reducing emissions.

In large part, of course, this is simply an expression of how this was the Brexit election, in which all other issues were squeezed out. Even the Green Party, after all, took the decision to foreground Brexit over the climate crisis by entering into the Unite to Remain alliance with the Lib Dems, whose own climate policies have only the dubious distinction of being not quite as poor as the Tories’. It would be a serious mistake, however, to conclude from this that there is no issue for climate campaigning and that it will all come right next time.

In the first place, we don’t have the luxury of waiting until the next election to get real action to address the climate crisis. Global heating does not respect the Fixed Term Parliaments Act. If we’re to have any chance at all of getting to net zero carbon emissions by 2030, we can’t wait until 2025 to start. In the second place, the election result has lessons for the climate movement.

The proximate cause of Labour’s defeat was its second referendum position on Brexit. (If you’re tempted to doubt this, explain why, in that case, the vast majority of the seats Labour lost were in Leave-voting areas. I’ll wait.) Labour’s Brexit policy in this election was however the final nail in a coffin built of decades of successive Labour leaderships’neglect of working-class communities outside the big cities. The Labour manifestos of 2017 and 2019 were promising a range of policies which would have helped those communities, but elections are not won by manifestos alone. You have not only to have the policies, but to convince the electorate that they are credible. Labour’s impressive social-media game helped it do this only with a limited section of the electorate. It seems that it fell foul of the Brexit culture war, where messages about Labour’s policies were seen as coming from the same sources as were lambasting 17.4 million Leave voters as ignorant racists. Ultimately, then, Labour failed by failing to campaign on a class basis. It wasn’t seen as fighting for the working class; itwas seen as middle-class activists despising them while still expecting their vote.

The relevance for climate campaigning is that the past year has seen the climate movement make pretty much all of the same mistakes. The XR approach has been very similar to the Corbyn project’s in its expectation that if we simply lay the facts out before the public, then they will automatically support us. At the same time, some of the thinking around disruptive actions has at times slipped from regarding the creation of inconveniencefor the public as a necessary evil to that inconvenience becoming the point. The nadir of this was the action at Canning Town tube. The spectacle of white, middle-class XR protestors facing off against a crowd of largely working-class, largely BME people just trying to get to work was a dramatisation of XR as a movement not of the working class but against the working class.clima

Canning Town was of course just one, ill-judged action and it is generally acknowledged to have been a mistake. It was however the sort of mistake that a movement can only make when it is detached from working-class communities. It has sometimes been argued that this is unimportant. If working-class people don’t or can’t engage with climate campaigning, then those who are more comfortably-off can ‘use their privilege’ to do it for them. The election result has just shown where this sort of thinking leads.

The focus now will be off electoral politics and on to campaigns, for action on climate change as much as against issues like the NHS sell-off and school cuts, but this fight back will have to be organised on the basis of class. For climate campaigning, this means an urgent turn to organising in working-class communities not at them. It means foregrounding Just Transition demands and working with the unions whose members will be most affected, not dismissing them as obstacles to be overcome. And it has to mean the death of any idea that working-class people are too blinkered or stupid to understand the climate crisis.