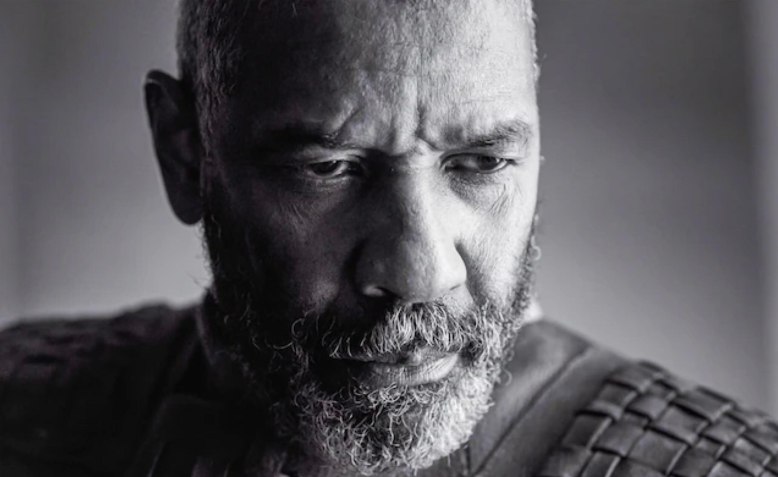

Scene from The Tragedy of Macbeth

Scene from The Tragedy of Macbeth

Joel Coen’s The Tragedy of Macbeth is a visual and aural feast, and while not flawless, shows that Shakespeare can work powerfully well on screen, writes Tom Lock Griffiths

Shakespeare’s body of work is virtually an entire artform of itself; an artform that isn’t designed to be read, nor principally to be seen. It’s an artform that must be heard.

Shakespeare is a sound art. Shakespeare’s language must be spoken, enunciated, articulated, delivered. The audience must listen.

That director Joel Coen and his often miraculous cast understand this, is one of the film’s great strengths. Coen also recognises that film too, is a sound art, (cinema isn’t a visual artform, it’s a visual and sonic art form, and has been for nearly 100 years). And here the richness of the language is matched by an equally elevated approach to the sound design and score, which proves to be a powerful combination.

Assassin’s Creed director, Justin Kurzel’s Macbeth (2015), while striking in its use of production design and cinematography (the three-minute trailer was the most exciting thing to come out of the project, with its ‘Game of Thrones’/music-video style production values), does not take this approach, and fails as a result.

Kurzel’s Macbeth starred Michael Fassbender as Macbeth and Marion Cotillard as Lady Macbeth, who sadly mumbled their way through the dialogue, missing the point that Shakespeare’s words must be understood to be properly appreciated. We must be able to revel in the sonic force of the language; it’s rhythms, its cadences, its undulating verse, and its barrages of clattering consonants. Otherwise, it’s not really Shakespeare. Kurzel’s film was underwhelming and emotionally flat. Style over substance.

If sound comes from the chest and from the stomach, his film lacked heart and lacked guts. Coen’s Macbeth, however, resonates through the body, chilling the bones and raising hairs, even before the first image fades up from black.

Witches’ voices

Kathryn Hunter (already a rightfully lauded Shakespearean actor) plays all three witches as one part: a multi-faceted schizophrenic whole. Her witches form a single troubled, uncanny creature, touched not only by madness, but by very real evil. She is a witch, the real thing, as real as witches were for Shakespeare; a black-magic incanting, devil-touched, force of darkness.

It’s a thing of sublime, skin crawling wonder to hear her three distinct voices, which open the film, from the darkness of a cinema, and then see the single, spidery form, with crooked, unnaturally bending limbs, from which the sound of her voices emanates. Hunter is exquisitely creepy as all three witches, and her performance should be heaped in awards for it. Every moment she is on the screen is a dark delight.

When she begins to flap her seemingly disarticulated arms, we hear the visceral flapping of leathery wings. She is not human, she’s a crow, a raven, a bat. Something both ancient and newly crawled from the pit. It’s the first clear sign that we’re in for an elevated sound experience too.

Coen reunites with long-time collaborators, composer Carter Burwell and sound designer Skip Lievsay, and they are at their career bests. It’s a visual triumph as well. Coen doesn’t set the film in the real world; he sets it in the authentic, uncanny world of Shakespeare’s play. It’s an austere, geometrical, black and white world which draws heavily for its visual style on previous black-and-white versions of the play such as Orson Welles’ 1948 version, and Akira Kurosawa’s 1957 film, Throne of Blood, with a good dose of German expressionism in the slanting doorways over ruined stone huts. There are also shades of Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet (1948) and Kaneto Shindo’s black and white horror masterpieces Onibaba (1964) and Kuroneko (1968) too, especially while Fleance hides in the long grass from the men who’ve just murdered his father Banquo. The setting, sound, music, and the stark black and white visuals are all brilliantly handled. And for the most part the language is spoken beautifully.

There are also some excellent supporting roles other than Hunter’s, and from parts that can pass you by in other productions. Brenden Gleeson’s King Duncan is perhaps the most Coen-brothers-esque characterisation of the film, with the possible exceptions of Banquo’s murderers, and a joyously seedy Stephen Root as the drunken Porter. Gleeson’s Duncan is an innocent, a terrible judge of character, but deeply likable in his bluff confidence in those around him, so much so that it’s perhaps the first version I’ve seen where his murder is truly upsetting. In her only scene, Moses Ingram, is an incredibly touching Lady Macduff, giving loving reassurance to her son as doom hurries towards them. Harry Melling as Malcolm, Alex Hassell as Ross (a part to good effect that has more prominence than any other productions I’ve seen too), and in an ever so brief turn as Seyton, James Udom, all deserve honourable mentions.

Flawed Macbeths

The rub comes however, with the two leads and their characterisation of the Macbeths. Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand, as Macbeth and Lady Macbeth, while in many ways very strong, certainly in how they speak the language, without airs, but clearly and with the power the lines deserve, don’t always hit the mark.

Of course, Macbeth is the better part when compared to his wife; he has more to say and more to do, and it’s arguably a fault in Shakespeare’s play that his Lady Macbeth is somewhat under-written. Certainly, (regardless of modern prejudices) it’s a part that has even more potential than for which it is given space. And this is certainly part of the problem.

While Washington lets the language carry him through, from the manly strength of warrior and veteran to murderous conspirator and finally to deranged tyrant, until her turn to madness, McDormand’s Lady Macbeth is frustratingly one-note.

So much so that when Macbeth tells her of his plot to murder Banquo’s son Fleance, her shock and surprise doesn’t land. If she’s been so uniformly doubtless and ruthless in her bloodthirsty courage so far, where does this pricking of conscience come from? She is too much the nag, the harridan: so much so that when Macbeth expresses early reticence about the murder of Duncan, she’s barely able to restrain herself from rolling her eyes at her cowardly husband. There is also a lack of the very real love and sexual attraction that motored the relationship of the excellent Kate Fleetwood as Lady Macbeth and (slightly histrionic but still entertaining) Patrick Stewart, in Rupert Gould’s production of 2010.

This undermines several key elements of motivation for both parts; why does Lady Macbeth exert such control, and why does this warrior and loyal subject give in so quickly to his wife’s pleas; why does Lady Macbeth lose her mind racked with guilt and grief; and why does Macbeth’s key speech, ‘tomorrow and tomorrow’, after the death of his wife, have such power and poignancy in its tightly held, cold delivery?

These questions aren’t quite as convincingly answered as they should be here, and it’s the comparative lack of warmth between the two leads and the lack of depth in McDormand’s portrayal, that seems to be the root of this structural flaw. It’s a real shame, as these are both very talented and experienced actors, and when mined fully, Lady Macbeth’s smaller part yields a great richness and complexity which is a little lacking here.

It’s difficult to know what happened. Did Coen give them misdirection, or not direction enough, and let these titans of screen do too much as they wished? If it is a fault in the direction, it’s the one misstep in what is an otherwise intelligent, bold, and often surprisingly good production. A production which shows that even on screen, Shakespeare lives or dies by how the language is spoken.

Join Revolution! May Day weekender in London

The world is changing fast. From tariffs and trade wars to the continuing genocide in Gaza to Starmer’s austerity 2.0.

Revolution! on Saturday 3 – Sunday 4 May brings together leading activists and authors to discuss the key questions of the moment and chart a strategy for the left.