This first-hand account of life on the ground under Operation Protective Edge shows the suffering, resilience and dignity of the people of Gaza, finds Adam Tomes

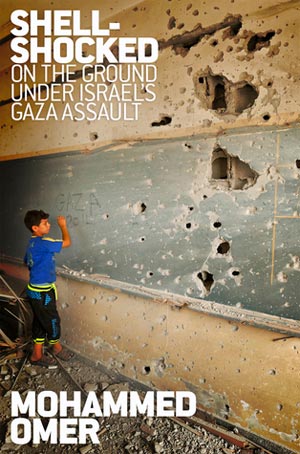

Mohammed Omer, Shellshocked. On the ground under Israel’s Gaza assault (OR Books 2015) 301pp.

Distorted reality

This book tells the story of the seven weeks of Operation Protective Edge, launched by Israel in July 2014, from the perspective of the people of Gaza. Each chapter is a journalistic record of what is happening as seen through the eyes of Mohammed Omer. The writing is clear, concise and evocative whilst remaining professionally detached. Within that attempt to provide a detached, historical record, a sense of deep and burning anger shines brightly without ever detracting from the author’s task. That task, it seems to me, as Eduardo Galeano argues in Days and Nights of Love and War (Monthly Review Press 2000), is to ‘make audible the voice of the voiceless’ (Galeano, p.8) and so to expose the ‘distorted reality’ (Omer, p.8) in which the people of Gaza live. In this, the author absolutely succeeds and it is a crucial task as the ‘Palestinian narrative is underrepresented in the media’ (p.10). Not only is this view underrepresented, but the horrific human cost in terms of lives lost and people being forced into abject, inhumane conditions, is rarely if ever told when covering this or any conflict. The inhumanity of violence and its consequences told through real-life stories is an essential lesson about this or any conflict.

This does not mean it is an easy book to read. Each short chapter is a news report from Omer that span the seven weeks of the conflict. This can give the book a repetitive feeling, and, when read in one sitting, there is a sense of being overwhelmed by the body parts, bodies in vegetable refrigerators (p.163), and the numbers of the dead, which reached over 2,200 in Gaza, whilst 73 Israelis lost their lives. Each chapter details the growing casualty list like a metronome which bludgeons your senses. However it is the human stories which open your eyes to the savagery that mankind can visit on itself. The stories are a way to explore the very specific tactics of the Operation, and its consequences, but also the amazing dignity and hope of the people of Gaza.

The people

It is the characters in this book which are its major assets. We are introduced to a wide range of people and given a clear window into their lives in Gaza, which helps the reader to understand some of the major issues. One such individual is eight-year-old Karam Abu Shanab, who was sheltering with his mother and three siblings in the al-Rafdeen school in Gaza City. His house and all his belongings had been destroyed in an attack and so he was forced to seek shelter in a school like another 240,000 people (p.158). Karam Abu Shanab tells of how he ‘can’t sleep in the night’ as his mind is filled with ‘bad images from the Israeli bombs’ (p.157), which comes as little surprise as 133 schools as well as 23 hospitals were hit as part of the attacks during the seven weeks (p.158). The simple fact that places of refuge and hope, which should be immune from targeting, were attacked reveals the savagery of the Israeli operation.

The story of Hani is one that sits with you long after you finish the book. His is a family of fifteen, sitting nervously under a corrugated tin roof listening out for the hum of drones, never knowing if it is a surveillance drone or a weaponised one. For safety, Hani splits his family into different rooms which is a ‘grim shell game of family members’ (p.20) that is played out in many homes across Gaza. The simple idea that this game is played out in so many homes with the hope that at least some of the children will survive shows the ‘distorted reality’ in all its grim colours.

There is also the story of Khaled Abu Sayed. His neighbour received a call from an Israeli automated machine saying their home was to be bombed and fled outside screaming at everyone to get out. Abu Zayed and his five children fled their house and within five minutes no-one was left within the neighbourhood. The houses were not attacked and Abu Zayed believes this is a tactic of psychological warfare ‘meant to terrorise and cause maximum “collective fear”’ (p.52).

Broader canvas

The author uses these individual, human stories with all their small details to give a broader image of the tactics used in order to raise questions about how such monstrosities can be visited on one people by another, and why the international community stands by without intervening. The tactics include the targeting of residential areas, churches and schools where people take shelter when they have lost their homes and hospitals. These types of actions can only lead to civilian deaths and gives the lie to the oft repeated claim across the western media that ‘Israel targets Hamas terrorists and not innocent civilians’ (p.37). It is hard to fathom how such actions cannot be seen to have broken the Geneva Convention and the basic rules of morality. Indeed in 2015, the UN Inquiry accused the Israeli state of multiple breakings of international law and potential war crimes, and described its human rights record as ‘lamentable’. It is worth thinking about the impact of these attacks on the mind-set of the people of Gaza, and this is best summed up in the words of 24-year-old Nawal Abu Asi who states ‘the more you displace us, we will remain. The more you kill us, we will plant happiness in the hearts of our children’ (p.150). It is worth noting that the report also accuses Hamas of breaking international law and that both sides refuse to accept the report’s conclusions.

Operation Protective Edge also targeted the already over-stretched and under-resourced infrastructure of Gaza. Attacks on water supplies, sewage, agriculture, electricity and mobile-phone networks bring with them a vast element of human misery. The deliberate targeting of electricity lines in one 24-hour attack leads to 90% of all electricity supplies to be out, leaving most families with two hours of electricity per day. This means food going rotten in the fridge, over 50% of the water and sewage systems collapsing, leading to the obvious health risks for over 900,000 of the 1.8 million inhabitants of Gaza (p.93). The attack on the phone network deprives people of the key method of warning others about imminent attacks, and the ability ‘to communicate with rescue teams’ (p.111). The phone network is also essential in keeping families connected in a time of such a great displacement of people. At the same time, such attacks massively limit news gathering from independent journalists such as Omer on the ground, as well as limiting the impact of social media, which has become a growing force in reporting the true cost of military interventions.

The long-term impact of this structural damage is huge in terms of cost, time to rebuild and misery. Shelter Cluster, an international Housing group estimates that it ‘will take twenty years to rebuild Gaza following the seven-week war’ (p.282) and that is based on the construction and humanitarian supplies being allowed into Gaza. In the past, Israel has restricted building supplies ‘fearing militants would use them to build military facilities’ (p.282). Gazans such as Abu Khaled al-Jammal are waiting for bags of cement to rebuild their own homes as he believes if he waits for the international community’s response, his children ‘will suffer the next ten winters’ (p.278).

Hope and dignity

Within this chronicle of the impacts of war lie stories which show the dignity, hope and resilience of a people forced to live in this reality. Women turn ‘spent tank shells that destroyed our homes into flowerpots’ (p.8), whilst students return to ‘bombed out schools to complete their education’ (p.8). In the al-Huda school, a group of forty women could be found ‘rolling the cake mixture and pressing crushed dates inside’ (p.150) to create Eid sweets for their children in the belief that the cake is a symbol of ‘resilience and resistance’ (p.149). During the seven weeks, over 4,500 babies were born in Gaza (p.215).

The stories of the rescue workers on the front line show their immense courage. Ayman Sahwan has been an ambulance driver for fifteen years for whom it has become the norm to round up injured civilians knowing that ‘the red flashing lights of the ambulance won’t protect him’ (p.129). He, like many others, responds to missile attacks and ‘makes the rounds to all the hospitals in an attempt to match up ripped and shredded body parts left in the rubble or scattered on the streets by Israel’s military’ (p.129). The bravery and commitment of these rescue workers is humbling for all as is the commitment of Omer to get the story from the ground out into the world.

The author

Great credit should go to Omer for writing this everyday chronicle of the seven weeks of Operation Protective Edge. His eye for detail is exceptional and his story telling clear, allowing the reader to ask and answer many questions for themselves. This is perhaps all the more remarkable as Omer lived through this terror with his wife and three-month-old son. His first report, ‘When my son screams’ is incredibly powerful and hard to read, but Omer sees it as his responsibility to his ‘people and the Israeli people to get to the truth’ (p.18). He places that truth out there and fulfils his promise to Jundia that ‘his voice will not go unheard’ (p.9).

“We’re all human”

This book is an historical chronicle of the experiences of the 1.8 million people of Gaza during seven weeks of the Israeli assault. The stories are at once both heart-breaking and awe-inspiring. Omer through his writing opposes and delegitimises any violence from whatever quarter and shows us that ‘we’re all human’ (p.18) irrespective of race, religion or birth place and that ‘strength lies in mutual peace’ (p.13). Continued aggression and killing by Israel, with its ongoing siege of Gaza, must be condemned as a course of action which can only result in more suffering, and prevent any possibility of peace, while the responsibility of those of us in the West is to hold our own governments to account for their support of murderous Israeli policy.

Notes

Mohammed Omer, Shellshocked: On the ground under Israel’s Gaza assault is available exclusively from O/R Books