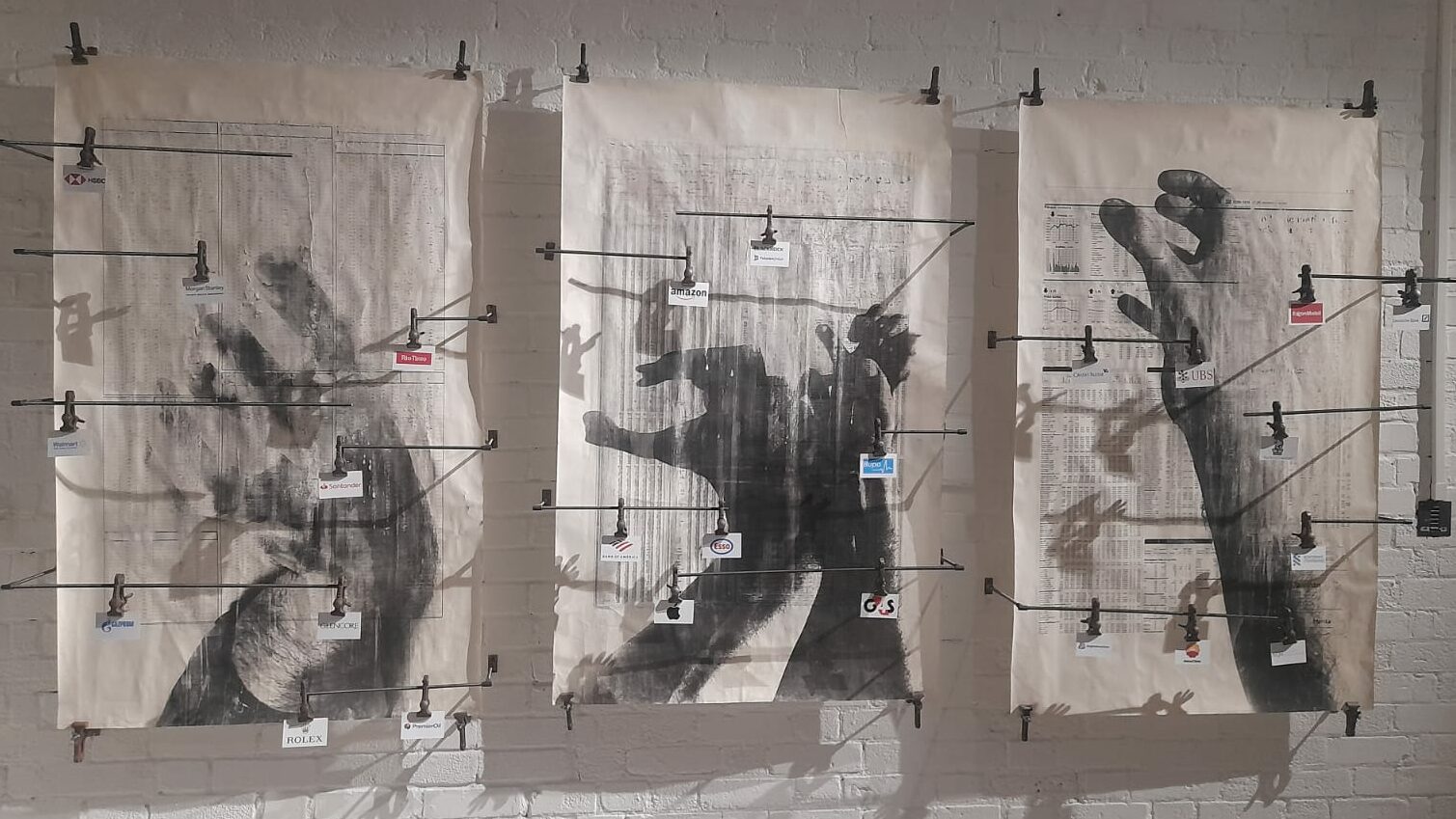

Silent Coup, Peter Kennard, a/political. Photo: Alia Butt

Silent Coup, Peter Kennard, a/political. Photo: Alia Butt

The works in Peter Kennard’s new exhibition make creative connections between capitalism and war, finds Alia Butt

After talks with G7 leaders who have been meeting in Japan this week, Ukraine’s president Volodymyr Zelensky has secured access to F16 fighter jets for his country’s armed forces. A different approach is being followed by the leaders of six African countries who have gained an agreement from both Russian President Vladimir Putin and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky for their engagement in peace talks. So, why is it that Western states have chosen to arm Ukraine, despite an understanding about the dangers of doing so, particularly after Putin made it clear that this can only end in escalation.

Peter Kennard’s exhibition which is on until 1 July in South London, shed some light on this question, both figuratively and literally. Kennard utilised broadsheets from the Financial Times newspaper, over which he superimposed shadows of images created through direct light shining on and off several times. The light was provided via closely placed lamps which were used to create shadows of images showing faceless victims in gas masks, huge missiles, and other motifs related to the atrocities of war.

Kennard’s use of the Financial Times broadsheets covered in numbers and sums, to many of us seem convoluted and meaningless on their own, but when paired with clear and morbid war-related images, they spoke to financial speculation as the driving forces often leading to war. A clear link was made between the arms market and the military-industrial complex that drives war and destruction in order to sell weapons, and the juxtapositions demonstrated this as a central part of the capitalist economy. Money is a strong driver of war, and there is much to be made in the arms game. This is one reason why war is relayed to the public as something vital and inevitable, when in fact this is by no means the case.

On the surface, Kennard’s work may have come across somewhat simplistic, though its timely significance was obvious immediately. Of course, power, subordination and imperialistic drivers are complex and broad, but the huge amount of money funnelled through the arms trade is essential to hold in mind at a time where money is a significant worry for most Britons, many of whom are forced to choose between basic amenities such as food or heating. At this time of economic turmoil, seeing most people in the country suffering hugely, Kennard’s work, to me, felt crucial. One million people are set to switch off their broadband due to a cost-of-living crisis leaving them unable to pay for internet. These people will therefore be priced out of accessing services and support due to many of these being run online. Kennard’s work highlights the importance of pushing back against government policy, which insists that so much taxpayer money is spent on the arms trade, and not least the return of US nuclear weapons to RAF Lakenheath in Suffolk, something that had been successfully campaigned against in the past. The government needs to be focusing on supporting working people in managing life, day to day, not nuclear weapons.

At a deeper level, through artistic technique and the cerebral impact left with the viewer long after they have left the exhibition, the relevance of the connections made are further understood. The multimedia technique effectively brought a sculptural aspect to the work, through its physical use of lamps, light and animated montage. It felt reminiscent of, though its outcome less obvious than, the montage techniques used by John Heartfield in the inter-war period, who utilised newspaper images to make clear the links between Nazi fascism and capitalist greed among other things, or indeed Kennard’s own images from the 1980s.

Kennard’s current technique of layering shadow on broadsheets creates a strong comparative element between the banality represented by the streams of numbers on the pages and the intensity of the human experiences projected over it via light. This juxtaposition allows a deeper impact to be experienced. The process of photomontage is one that can bring a sense of truth back into the medium of photography; photographic images can often dissolve the true ugliness of the subject it is shooting, due to the beauty and aesthetic nature of the art. This can be seen in the photomontage work of innovators such as Hannah Hoch and Heartfelt, who are more direct with their comparisons.

Kennard’s contemporary work, however, provides a sophistication and simplicity that somewhat reduces the sensationalism that the aforementioned Dada work sometimes carried. Kennard’s work felt more about the hidden truths and symbolic importance of institutions such as the Financial Times, a newspaper within which evidence can be found to make links between capitalism and war. However, rather than printing these images onto the sheets and instead projecting them momentarily, Kennard allows the connection between war and money to shine directly onto the page and disappear, only to re-emerge once again; a connection that is likely to re-emerge whenever one subsequently picks up a copy of the paper in the future.

Silent Coup is on until 1 July at a/political, 6 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AA

Join Revolution! May Day weekender in London

The world is changing fast. From tariffs and trade wars to the continuing genocide in Gaza to Starmer’s austerity 2.0.

Revolution! on Saturday 3 – Sunday 4 May brings together leading activists and authors to discuss the key questions of the moment and chart a strategy for the left.