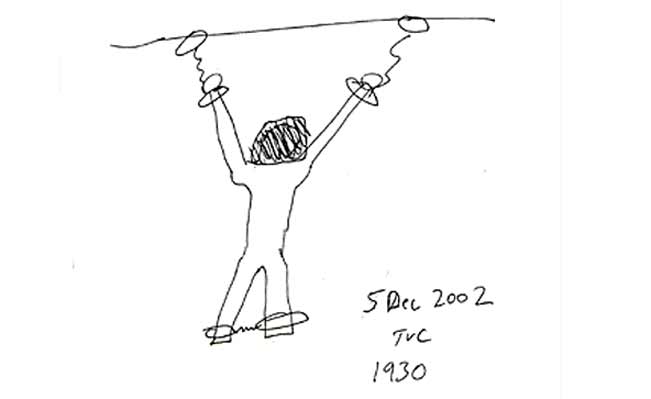

Soldier's drawing of torture methods used on Dilawar, the prisoner depicted in 'Taxi to the Dark Side'

Soldier's drawing of torture methods used on Dilawar, the prisoner depicted in 'Taxi to the Dark Side'

Extracts from chapter 2 of None of us were like this before by Joshua E. S. Phillips. The book explores the legacy of torture in the “War on Terror,” told through the story of one tank battalion.

Combine the words “US” or “American” with “detainee abuse” or “torture,” and the response will likely contain “Abu Ghraib” or “Guantanamo.”

But the American use of torture during the war on terror did not begin with Abu Ghraib, nor did it begin in Guantanamo. It’s easy to lose track of that fact, given the powerful images associated with both of those facilities: the Abu Ghraib pictures of sexual sadism, and photos of hunched Guantanamo detainees clad in orange jumpsuits and darkened goggles, surrounded by coils of concertina wire.

“The White House always put forward that Abu Ghraib was an exception, just some rotten apples,” said John Sifton, a former senior researcher on terrorism and counterterrorism at Human Rights Watch. “But US personnel in Afghanistan were involved in killings and torture of prisoners well before the Iraq war even started. The story begins in Afghanistan.”

No flashy photos show these abuses, at least none that has emerged into the news media with the same force as the images from Abu Ghraib. It takes an attentive reader to identify these cases and track their chronology. And it takes a dispassionate approach to parse out when and where government officials willfully contributed to coercive interrogation, when officers and soldiers acted with relative autonomy (or without explicit instructions), and how commanders and officials were complicit in overlooking abuse.

Human rights organizations recorded cases of detainee abuse shortly after US boots hit the ground in Afghanistan in 2001. Some instances occurred in the heat of battle or when troops were “roughing up” detainees upon capture. To be fair, some roughing-up is a by-product of detainee arrests that is fairly typical of combat situations, and is by no means exclusive to the US military. But consistently roughing up suspects when they are captive in a detention facility is a different matter. During the early phase of US combat operations in Afghanistan, some of these abuses were relatively mild. Others were quite severe. Some even turned lethal.

Perhaps the most famous early cases of US prisoner abuse involved two detainees known as Habibullah and Dilawar. The events surrounding their deaths occurred in Afghanistan in December 2002. Three years later, the New York Times first detailed their experiences and the early abuses at the Bagram Air Base. Over time, Habibullah and Dilawar’s stories have gradually gained more public exposure in print and in film (e.g., in the Oscar-winning documentary Taxi to the Dark Side). But these events deserve to be revisited because of the timing and what it reveals about the early development of US abuses.

Journalists had already interviewed many of the guards who abused detainees in Bagram. Yet I never heard them provide an explanation that seemed adequate; most of their reasoning seemed incomplete at best and self-serving at worst. And so, in 2007 I traveled to Afghanistan to interview former Bagram and Guantanamo detainees who could describe events from an Afghan perspective.

Years after the US-led coalition toppled the Taliban in 2001, violence engulfed southern and eastern Afghanistan, making travel to provinces like Khost increasingly difficult. Car travel, conceivable in the years just following the US invasion, was now strongly discouraged. By mid- 2007, the road connecting Kabul to Khost was rife with banditry and talibs, making it especially perilous. Non-Afghan travelers typically sought out limited air transport to Khost, which meant flying into Forward Operating Base Salerno—the very base where Dilawar and his companions from Khost first arrived.

Wahid Amani, my translator, fixer, and friend, accompanied me there to retrace some of the steps of those who were released from US captivity. Wahid was a twenty-seven-year-old journalist from Wardak province who worked as a freelance journalist for several years, and then as a reporter and trainer with the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR). We worked together for IWPR, and he occasionally assisted foreign journalists with their projects. But he grew uneasy about taking assignments in provinces like Khost, where violence had become prevalent.

pp.27-30

Dilawar came from a family of seven brothers and three sisters, and was always considered quiet and shy. When he was seventeen years old, his family married him off to a local girl from Khost, and soon afterward they had a daughter, Rashida.

His parents were native Afghans, but like his other siblings, Dilawar was born in Pakistan. They fled their homeland during the mujahideen wars that erupted after the Soviets invaded in 1979. Like many Afghan refugees in Pakistan, they lived day to day, laboring for migrant wages.

No one in Dilawar’s family was sympathetic to the Taliban. But after the Taliban gained control of Afghanistan in 1996, the violence declined for a while. That respite offered Dilawar’s family an opportunity to return to Khost and claim a plot of land where they could grow corn and grain.

Shapoor, the oldest sibling, used the wages he saved from working in Dubai to start up a business buying and selling goats and cows. Dilawar was responsible for shepherding the goats, taking them out to the mountains for grazing and returning with them at night. Eventually they built a simple seven-room house with stone walls in the Yakubi district.

Yet the family regularly encountered problems with the Taliban. In Khost, talibs routinely harassed locals who were caught in the streets instead of attending the mosque during prayer time. One day, a small group of talibs stopped Shapoor’s car, yanked him out, and beat him up for disobeying a law under the Taliban regime: listening to music.

Dilawar was Shapoor’s favorite sibling, and Shapoor worried whether his little brother could survive the tough environment of Afghanistan under the Taliban, where religious laws were enforced with violent severity. As a teenager, Dilawar could grow only wisps of facial hair, and his family urged him to stay home since he couldn’t fulfill the beard- length requirements imposed under the Taliban.

Dilawar didn’t have the frame or stamina for hard labor. After his shepherding work, he would move stones from the mountains with the family tractor, selling them to locals for house construction. But Shapoor noticed how Dilawar struggled with his job, and how it wore out his slight body.

The money Shapoor had saved from working at hotels and driving taxis in Dubai was enough to buy Dilawar a Toyota Corolla. Shapoor hadn’t provided his brother with a wedding gift, but knew that this present would be more meaningful, since he would no longer have to haul heavy rocks with a clumsy tractor. Dilawar was overcome by his brother’s generosity. He finally had the means to pursue work that was less physically taxing.

On the day Dilawar was abducted, Shapoor was about thirty minutes outside of Khost, where he had gone to sell sheep and goats, when a taxi driver edged alongside him and rolled down his window. It was the taxi driver who had been traveling on the same road where Dilawar and his passengers had been pulled over. He told Shapoor that they had all been arrested and that the Toyota’s windows had been smashed. Shapoor feared what had happened to his young brother.

Back in Bagram, the detainees were roused late at night for questioning. Soldiers poured ice-cold water on them and ventilated the prison to allow the freezing night air to gust over their wet bodies.

Then the guards came with chains.

By now the prisoners were accustomed to having their wrists bound. But the soldiers were lifting them by their arms, hoisting them upward by chains attached to the ceiling. The weight of their bodies, pulling downward as their arms were stretched upward, made breathing diffi- cult.

The soldiers still wouldn’t permit them to relax, often making noise to frighten them or keep them awake. Detainees remained hooded, causing further disorientation.

“We did not know if it was day or night,” said Parkhudin. “The lights were always on.”

There were bathroom breaks twice a day for a few short minutes. During interrogations, the men were lowered, unchained, and ushered to small rooms for questioning. Their limbs creaked as their bodies returned to a normal position.

“We could not walk because our feet and hands were hurt,” said Parkhudin.

Then the questions began.

Why did you have the numbers from Dubai? What about the walkie- talkies? What were you doing with the electrical stabilizer? Did you use it to launch rockets?

Interrogators occasionally presented photographs and questioned prisoners about the subjects contained in them, such as Osama bin Laden and Taliban leaders. Troops applied various kinds of pressure if prisoners said they couldn’t identify people in the photos, if they didn’t have answers, or if they seemed evasive in any way.

Qader Khandan said he was forced to do push-ups while a soldier stood on his back. Other detainees said they were beaten. Some were ordered to hold their bodies in stress positions for hours, their arms and legs trembling from exhaustion, their ankles swelling, pain shooting through their extremities. Then interrogation sessions ended, and they were once again hung from chains.

It became a routine. Some prisoners claimed they were chained ten days and ten nights, their toes just scraping the floor, lowered just for interrogation sessions and short bathroom breaks. Again, no talking was permitted. More infractions meant more beatings on their arms, legs, and feet. While suspended, prisoners were vulnerable and could not shield themselves from the blows.

Parkhudin couldn’t see Dilawar, but could hear him being beaten. He seemed especially distressed, more so perhaps than the others.

“I could hear what he was yelling and that he was crying, asking for his mother, asking, ‘Where are you my God?’ ” Parkhudin recalled.

Soldiers laughed when they heard Dilawar’s anguished cries. Fellow detainees thought soldiers were taunting Dilawar “just to make fun,” said Parkhudin.