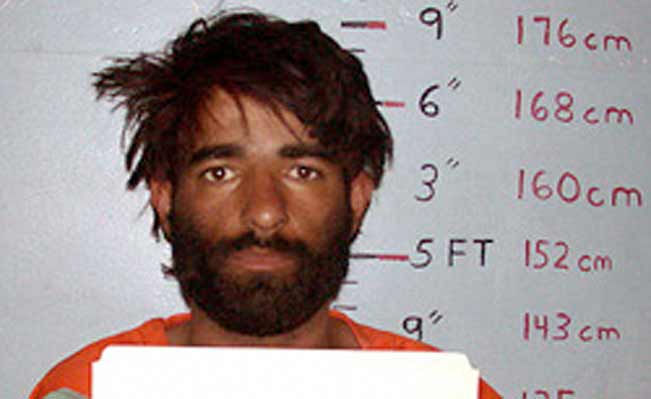

Taxi driver Dilawar - beaten to death by his interrogators

Taxi driver Dilawar - beaten to death by his interrogators

An extract from None of us were like this before by Joshua E. S. Phillips. The book explores the legacy of torture in the “War on Terror,” told through the story of one tank battalion

Khandan was hung by his wrists for days and lowered for two or three hours a day for interrogation. Soldiers lowered him so he could relieve himself and then, he said, they would strike him and roll him down a flight of stairs. Khandan soon feared the bathroom and reasoned it would be safer to consume less food and water. After three days he stopped eating and drinking.

Eventually a soldier pleaded with him to stop fasting and assured him that he would be able to use the bathroom safely. Many of his fellow detainees could no longer control their bowels, and the prison began to smell of human waste. Khandan saw flecks of dried blood on the floor whenever guards removed his hood to give him water. It seemed that some prisoners had sustained grave injuries from their detention in Bagram. One of them was Habibullah‚Äîsometimes referred to as Mullah Habibullah‚Äîthe brother of a Taliban commander from Afghanistan’s Oruzgan province.

During his detention, Khandan heard guards tussling with Habibullah. Other prisoners heard Habibullah exchanging shouts with the guards, and then they heard soft thuds—what seemed like body blows. Next they heard what seemed like sputtering sounds coming from Habibullah. And then silence. Habibullah died from his injuries on December 4, 2002.

The interrogations did not stop, and the soldiers resumed their routines. Prisoners once again heard the standard battery of questions in the interrogation room: How long have you known Osama bin Laden? How many times did you meet him? Where are the Taliban commanders? Who did you work for? How long have you supported al Qaeda? Over time, prisoners grew increasingly weary and less articulate. There were also misunderstandings during interrogations because Bagram’s Afghan translators had difficulty understanding the prisoners from Khost. “All the translators had problems with us because of our accent,” said Parkhudin. Some troops believed detainees were purposely confusing interrogators and evading questions by feigning miscommunication.

Once again Dilawar pleaded with his captors. “I’m just a taxi driver,” he said. “The only reason that they arrested me was because of the stabilizer they found in my car. That is why they brought me here.” “He was crying,” recalled Khandan. “It was all because of the pain, and he was saying ‘Oh, my mother. Oh my God. Oh, I’m about to die.’ ” But no one heeded his words. And soon Dilawar, too, succumbed to his injuries.

Word about Dilawar’s death gradually percolated into Afghan governmental channels. Afghan officials puzzled over how to convey the news to his family and how to return his body to Khost. Eventually a govern- ment worker who knew about Dilawar contacted his uncles. “My family, my uncles, they didn’t let me know,” said Shapoor. “They just went to Kabul by themselves and brought the body.”

Dilawar’s body traveled from Bagram, between family houses, until it reached Yakubi. At last, his uncles broke the news to his father, and the family crumpled in sorrow. Dilawar’s prized Toyota sat in front of the family house, and his mother wept whenever she saw it. Bits of shattered glass still encrusted the edges of the windows. Shapoor eventually sold it for $1,000 and used the money for Dilawar’s funeral ceremony. Since then, said Shapoor, whenever Dilawar’s parents heard his name “they would get very weak, and I had to take them to see a doctor.” His mother even developed a respiratory condition from the grief, said Shapoor. Dilawar’s five-year-old daughter, Rashida, understood her father had been captured and killed, but no one could make sense of it. No one understood what anyone would want with Dilawar, the most unassuming member of the family. All they had were documents that established he had been in US custody. Nearly a year after their arrest, Parkhudin and Zakim Khan were cleared of their charges and returned home. Shortly after they arrived in Khost, they traveled to visit Dilawar’s parents. Dilawar’s mother pleaded to hear what happened to her son.

The released detainees could tell that Dilawar’s death had already exacted a devastating toll on his family, and they didn’t want to add to their grief. They simply couldn’t bring themselves to convey the truth about Dilawar’s suffering to his parents. Parkhudin insisted “there was no punishment at all … the Americans did not beat him and they did not beat us.” Maybe Dilawar was sick, said Parkhudin to his parents, and perhaps he had a health problem that led to his death. “I told them that Bagram was a comfortable place, and the Americans were very nice people.”

pp.34-5

Due to legal decisions drafted by the Bush administration during early 2002 prisoners were regarded as “enemy combatants,” and many US troops understood that al Qaeda and Taliban detainees weren’t entitled to the minimum standard for humane treatment afforded in the Geneva Conventions’ Common Article Three. But the other memos pertaining to coercive interrogation probably had far less influence on troops‚Äîespecially early on. In August 2002, Jay Bybee, then head of the Office of Legal Counsel, signed off on a memo to provide the CIA with the legal framework for harsh interrogation. That memo, often called “the Bybee memo” (or the “torture memo”), defined physical torture as “equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death.” Later that year, in December, the Department of Defense’s general counsel, William J. Haynes II, sanctioned coercive interrogation, known as Counter- Resistance Techniques, exclusively for Guantanamo’s interrogators.

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld later approved the techniques contained in the Haynes memo. Additional memos and directives authorizing US forces to use coercive interrogation emerged after 2003. It is possible that there were other memos that haven’t been made public, authorizing troops in Afghanistan to apply torture or abuse. Perhaps there is proof‚Äîthrough memos, verbal orders, or military directives‚Äîthat senior officers directed soldiers to rough up detainees and even outlined the techniques that troops could employ. That such evidence exists has been a common belief among those who have researched and read about US torture. “There seemed to be a regimen or a system in place where prisoners were routinely roughed up as a matter of policy,” observed a human rights researcher I knew who had interviewed dozens of former detainees from Bagram and Kandahar. “Someone had to issue an order or directive. American soldiers just don’t do that sort of thing on their own.”

To date, no evidence has been found that senior military commanders issued explicit directives to soldiers in Afghanistan to abuse and torture detainees during the time Habibullah and Dilawar were in US custody. According to Reed College professor and noted torture expert Darius Rejali, high-ranking officers and government officials typically have not ordered torture policies in most documented cases of torture. Instead, in most historical cases, “torture began with the lower downs, and was simply ignored by the higher ups.”

If the cases of Habibullah and Dilawar mirror the same pattern of guidance and leadership (or lack thereof), they force us to ask: How do we account for cases in which troops lacked directives and still committed abuse? It is too easy, and sometimes inaccurate, to claim that heated combat operations lead to torture. So what happened?

Extract from Joshua E. S. Phillips, None of us were like this before (Verso 2010)

Stop the War Coalition, CND and the British Muslim Initiative have called a demonstration against the increasingly bloody, expensive and failing war in Afghanistan.