Stephanie Urdang’s memoir reveals her courageous personal involvement in the struggles against apartheid and for national liberation in southern Africa, finds Jacqueline Mulhallen

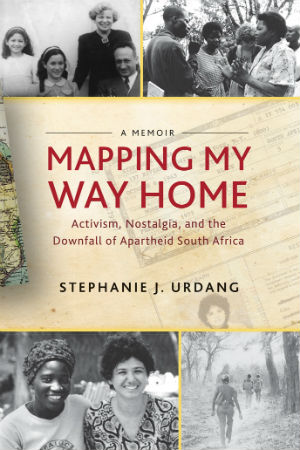

Stephanie Urdang, Mapping My Way Home: Activism, Nostalgia and the Downfall of Apartheid South Africa (Monthly Review Press 2017), 304pp.

Memoirs of those involved with political campaigns can be illuminating since the personal aspect can shed light on aspects of the campaign which are not always covered in a strict historical account. I am not sure if this is the case, however, with Mapping My Way Back Home.

Stephanie Urdang appears to be a concerned, generous and courageous woman. Mapping My Way Back Home tells the story of her life, travels and experiences and how her attitude was influenced by the women’s movement of the 1960s. However, it is a book about how she is affected by the great events she lived through rather about the events themselves.

She was born to a privileged white Jewish family in South Africa in the middle of World War Two, a family which had fled the Tsarist pogroms. Her father, who she describes as a Trotskyist, was a lawyer and devoted his life to acting for non-white Africans until he was compelled to leave South Africa since his practice was no longer legal. Stephanie Urdang herself worked as a secretary for an organisation providing legal aid, and she describes the frightening experience when it was raided and closed down. She no longer had a job, and she and her friends who opposed the apartheid regime decided to leave and carry on the fight against the system elsewhere. Her parents moved to London, and Stephanie left shortly after for the USA with her boyfriend, whom she later married.

After working as a secretary for a community group, Stephanie began editing the journal Southern Africa, which featured articles on the struggles against apartheid in South Africa and colonialism in other countries. Her job helped her husband pay his way through college. When he graduated, Stephanie decided to spend six months travelling in Africa. Her work with Southern Africa meant she had contacts with many leading African revolutionaries and she followed up introductions in order to visit countries to which she might not have otherwise had access, including the war zones of Guinea-Bissau, and later Mozambique.

These chapters of the book are very interesting as they outline the impact on women of these wars of independence. She met female fighters who guided her through war zones, and she was actually in Guinea-Bissau in 1974 when the Portuguese revolution took place, and the colonial war finished. She returned to both countries, and eventually completed two books about them, published in 1979 and 1989. She describes how the promises made to the women were betrayed, and discusses the problems in Mozambique caused by the South African apartheid government’s creation of a civil war. It was not until 1984 that she returned to South Africa itself, where she felt almost a stranger. Since then she has made a number of visits.

What is lacking from this book is any in-depth political analysis. Just over a year ago I wrote a review for this journal of a book entitled Selling Apartheid: South Africa’s Global Propaganda War by Ron Nixon. I thought at the time how fascinating it would be to read the other side of the story. Stephanie Urdang was one of the people in the American Committee on Africa and the Africa Fund involved in fighting the South African propaganda, and so she was ideally placed to tell the story of the anti-apartheid campaign in the USA. Since the subtitle of the book is ‘Activism, Nostalgia and the Downfall of Apartheid’, I thought that it would do this. However, what she says about it amounts to only two or three pages (pp.242-5).

Her father’s authoritarian style of Trotskyism led to her turning to a kind of feminism which supported her personally and stood her in good stead when writing about the women of Africa. However, it is not sufficient for her to understand and explain why the revolutions in Guinea-Bissau, Mozambique and South Africa have not led to the world they were envisaging. She reports discussions with women who have been involved in the struggles in Mozambique and South Africa. One woman says;

‘When I was young, […] I learnt a new Mozambique where there would be equality. This is not the Mozambique of today. How is it possible for some people to become so rich in a country that is so poor?’ (pp.284-5).

Stephanie has no answer beyond saying that they did the best they could. Her criticism of one of the leaders of Guinea-Bissau for having an income much higher than the average in the country, does not appear to lead to a recognition that the class structure is being perpetuated (pp.173-4); at least she does not discuss this.

Her conclusion ‘whether South Africa can break its descent into corruption and bad government I cannot know or guess. But I have not given up hope’, is optimistic. She believes she has seen revolutions in Africa in her lifetime and knows that ‘a determined people […] cannot remain crushed forever’ (p.302). However, she does not offer any lessons to be learned from her experience. Specifically, she does not identify that apartheid and colonialism are direct products of capitalism, and that the failure to seriously challenge capitalism itself is the root cause of the failure of these revolutions.

It may be that Stephanie Urdang saw the book as her own personal story and therefore left politics out of it. However, the politics she left out would have informed the book and given it a context; it would perhaps have helped her understand what African women thought they were fighting for, and why they now feel let down; and it would have offered a way forward.