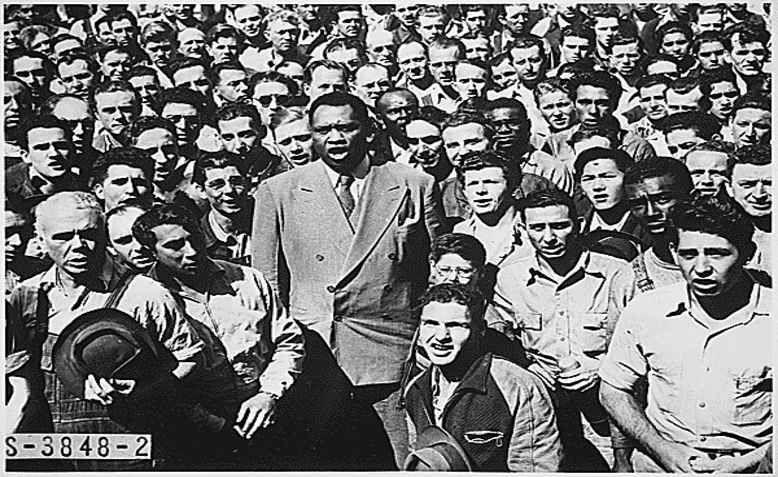

Paul Robeson, Oakland, California, 1942. Photo: the US National Archive on Flickr

Paul Robeson, Oakland, California, 1942. Photo: the US National Archive on Flickr

Paul Robeson’s extraordinary life is a lesson to us today, writes Tayo Aluko

“Colonial peoples … see how under the great Stalin millions like themselves have found a new life. They see that aided and guided by the Soviet Union, led by their Mao Tse-tung, a new China adds its mighty power to the true and expanding socialist way of life.”

Paul Robeson wrote this shortly after Joseph Stalin died in 1953. It is interesting to speculate what he would have thought of the recent celebration of the 70th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China, coinciding as it did with the massive protests on the streets of Hong Kong.

On the one hand, there is the show of tremendous military might in Beijing, impressive (and frankly, scary) as it was: how is it that such militaristic displays are still so necessary in this day and age? On the other hand, how come so many Hong Kongese apparently distrust their leadership so much that they prefer the prospect of being re-colonised by the dreaded British imperialists over their relationship with “Communist” China? Would today’s China bear any resemblance to the state that Robeson envisioned when he so fervently expressed his admiration for Mao, to the extent that he recorded and popularised the song that would become the Chinese National Anthem? Would he consider the words “Arise, ye who refuse to be slaves!..” outdated, inappropriate or ironic, bearing in mind what one hears about the fate of Uigar Muslims, the suppression of free expression on the mainland and in Hong Kong? And Russia – is it anything like the socialist paradise that Robeson and many like him dreamed of? Can either nation be said to live up to the hopes of the socialists of the 1940s and earlier?

The reasons for those hopes not being realised are far too numerous and complex for this writer to even begin to understand or analyse, but it is noteworthy that back then, each nation was in the firm grip of a strong man who considered himself the embodiment of the people’s aspirations, albeit as dictated by the Party elite.

The failure of the socialist societies to fully flourish anywhere in the world has been due to various combinations of the ruthless determination of those Robeson called “the greedy, profit-hungry, war-minded industrialists and financial barons” of the West (and indeed within the would-be socialist countries) to thwart their progress at every turn, and some socialist leaders considering themselves almost omnipotent. It will long be argued where on that spectrum one would position figures like Fidel Castro, Kwame Nkrumah, Hugo Chavez, Robert Mugabe, Patrice Lumumba, Muammar Gaddafi, Maurice Bishop, Samora Machel, Thomas Sankara or Julius Nyerere; but it is clear that in none of those men’s countries has the road to utopia been smooth, nor has that destination been reached, or as in the case of Cuba or Venezuela for example, been enjoyed undisturbed for any length of time.

Another socialist experiment that Robeson supported in his day was the establishment of the state of Israel, complete with Kibbutzim, which epitomised the desire of the Jews to live in a society based on cooperation, equality and communal living. Based on what one gathers from even mainstream media, the ideals of early socialist Zionists, communists, and their supporters like Robeson have not stood the test of time, and an interesting similarity with failed socialist experiments elsewhere is that despite the long list of powerful Israeli leaders (many of whom cut their teeth in the military), one struggles to identify any who stand out as the embodiment of peaceful and cooperative co-existence with their neighbours, and with citizens of all faiths, and none.

Robeson, whose own father had escaped slavery from North Carolina, always talked of the similarity between the stories of “the Jewish people” and those of his own ancestors. He learned, spoke and sang in Yiddish, and did as much as anybody to popularise “Negro Spirituals” – songs with which enslaved Africans in America, taking inspiration from old testament Bible stories, musically expressed their longing for peace, freedom and deliverance from bondage. Furthermore, the centuries-long persecution of Jews in Europe and elsewhere, which led to massive Jewish migration (particularly to the United States), resonated so much with the conditions of African Americans endured both during slavery – often using Spirituals as secret codes when preparing their escape (‘Steal Away to Jesus’, for example) – and in the Jim Crow era, to the great, freer metropolises like New York, Detroit and Chicago.

As total equality for Blacks continued to prove elusive even in the North, Robeson became increasingly convinced that Democratic Socialism was the only route to total emancipation of Africans in the Americas and in the Motherland, because equality for all people was enshrined in socialism, as was the notion that collective action, as embodied in Trade Unionism, was the only way of combating the power of the capitalist class. Robeson was one of the first people to see that the labour movement in his country could not succeed without Black people having full involvement in unions (including the leaderships), and simultaneously that civil rights for Black people could not be fully achieved without the white working class being allies in the Black struggle. He also went to great pains to suggest that women needed to be an equal part of the leadership of the civil rights struggle, and that the struggle for equality at home must not be divorced from anti-colonial and anti-imperialist struggles worldwide.

Decades ahead of his time therefore, Robeson understood well the concept of interconnectedness between causes and struggles. The fact that so few people around him (or in the world generally) had his level of understanding then, was an example of his rare insight and intellect. In a man who already had a command of over a dozen languages and had demonstrated superlative skills as a sportsman, a singer, actor and orator, the term “genius” begins to seem appropriate.

It is often said however that there is a fine line between genius and insanity. Considering the pressure and persecution he had to endure from all sides: from his government to Black collaborators and informers; the painfully slow progress in achieving peace and equality; his discovery of the extent of people’s suffering under the Soviet regime, and his decision to not speak about it, it is possible that his gushing praise of Stalin and Mao might have been a combination of the first signs of the mental illness to which he succumbed some years later (he attempted suicide on more than one occasion), and an angry show of defiance to the authorities and the public who had treated him so unfairly and harshly when all he strove for was a fairer, more peaceful world.

“Scared of dyin'” from Call Mr. Robeson. Photo: Alan Humphreys

“Scared of dyin'” from Call Mr. Robeson. Photo: Alan Humphreys

Robeson’s mental troubles could serve as an important lesson for his country: failure or refusal to discuss traumatic events of the past, to face uncomfortable truths, is bad, very bad, for the (collective) psyche. That the U.S.A. is literally killing itself is suggested by domestic terrorism, the capitalist health and pharmaceutical markets, and oil addiction and other ills.

Paul Robeson returning today would likely be confused by the goings on in Russia and China, yes, and disappointed by the lack of progress in the former colonies. He’d be less surprised by the disastrous effects of the triumphant capitalist system on billions of people, and on the environment. He’d be encouraged that so many of us are finally waking up to the climate emergency, and beginning to take dramatic steps to demand action from our leaders.

He would remind us that this is precisely why it is so crucial that all progressive causes and groups join forces; that there is far greater power in the hands of ordinary people working together than there is in those of the most apparently fearful of tyrants.

Finally, he would urge us to add one song to our repertoire as we march on the streets and occupy the citadels of power: the Spiritual ‘Joshua Fit de Battle ob’ Jericho’, which recalls how Joshua commanded de chillun’ to shout / an’ de walls come a tumblin’ down.

Tayo Aluko is the writer and performer of two one-man plays: Call Mr. Robeson and Just An Ordinary Lawyer.

You can read part one of this two-part article here.