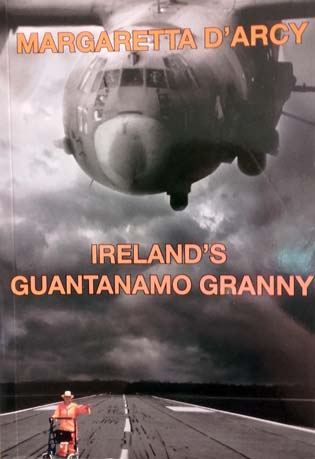

Margaretta D’Arcy’s magnificent stand against Ireland’s complicity with US rendition is vividly told in Ireland’s Guantanamo Granny, finds Ellen Graubart

Margaretta D’Arcy, Ireland’s Guantanamo Granny (Women’s Pirate Press 2015), 148pp.

Margaretta D’Arcy is an Irish actor, writer, playwright, poet, film maker, radio broadcaster and peace activist, born in 1934 to a Russian Jewish mother and an Irish Catholic father, who fought for Irish freedom from behind prison walls. In 1957 she married the playwright and author John Arden, an English Marxist playwright who at his death was lauded as having been one of the most significant British playwrights of the late 1950s and early 60s. She has campaigned for Irish freedom and neutrality, for civil liberties and women’s rights and was a leader of the women demonstrating on Greenham Common during 1981 to 2000 (pp.16-17) against the presence of US Cruise missiles based there. In 1960 she and her husband, along with many artists, filmmakers, actors and playwrights connected with the Royal Court Theatre, joined the Committee of 100 to launch a campaign of non-violent direct action against nuclear weapons.

In 2012, D’Arcy and fellow activists discovered that Shannon Airport was being used illegally as a transit point for US troops taking prisoners to Guantanamo Bay, in spite of the fact that Ireland is a neutral country. There are meant to be restrictions on flights landing, which must not carry arms, ammunition or explosives, and it should have nothing to do with any aspect of military exercises or operations (p.19). She tried to have a conversation with the Irish state about its contravening of its neutral status in allowing Shannon airport to be used for war and torture by the Americans, but the state could not answer her, nor could it defend its behavior on moral grounds. She therefore became an enemy of mainstream society. To get the state to listen to her she had to annoy the authorities by breaking a byelaw;and because she refused to sign a bond that would make her complicit with war crimes, she had to be jailed. She had become a threat to the state, which then used its power to silence, humiliate and denigrate her.

In her struggle to force the Irish state to accept the abundant evidence of its breach of international law and collusion with US imperialism, she reveals state corruption on a global scale. She also exposes the UK’s role in the extradition of prisoners to Guantanamo: a suspected CIA jet was used in an attempt to get NSA whistle-blower Edward Snowden through Shannon airport in 2014 (p.110). The CIA use of Shannon airport continues to this day.

In spite of the state’s efforts to keep the whole matter out of the public eye, word did get out. Her fellow prisoners, who had scorned her for refusing to sign the bond – pledging not to enter non-authorised zones at Shannon airport – that would have released her from prison, now gave her their full support. Pickets outside the jail organised by Shannon Watch were witnessed by their visitors. Protests followed elsewhere.

A visit to the prison by the wife of the Irish president to persuade her to sign the bond was leaked to the Independent, the Sunday Timesand the international press. She received letters of support and drawings from school children, cards from anti-war activists and women’s groups from Sweden. She got support from Global Women’s Strike and from the US as well as from politicians and local councils, and much more. Meanwhile, the anti-austerity campaign was growing and the water charges were soon to be put in place. Garda whistleblowers were revealing corruption and cronyism on a daily basis: the Irish public was ready for a fight.

D’Arcy has also exposed the effect of the brutality of the state on the ‘little’ people she shares various prisons with, who are treated with contempt and forced to endure awful prison conditions. She quotes from Nelson Mandela:

‘No one truly knows a nation until one has been inside its jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens but its lowest ones’ (p.103).

At the time of her arrest, she was 79 years old, a grandmother with cancer and a physical disability, and had recently lost her husband to cancer. This is her story, based on extracts from her diaries, her perceptions and records of the period, of a journey from protest to imprisonment – because she dared to delve into the dark secrets of a state desperate to keep them hidden. She has structured her story in the form of a stage play, beginning with a timeline and cast list, followed by a prologue, three acts and an epilogue, thereby creating a classical frame for the chaotic content and her informal style of writing, which she took directly from the journals she kept over a number of years.

Material that could have been dry and colourless D’Arcy has woven into a vivid fabric of poignant human stories, told with wry humour and unsentimental pathos, and not without occasional comic relief. In one of her attendances at court she turns up in an orange jumpsuit – Guantanamo style – and a Zimmer frame, plus two wheelbarrows full of documents. She announces that she is a whistle-blower, whereupon she produces a whistle, which she then blows (p.45).

There is a serious intent behind this act of pantomime – D’Arcy sees courts as a public forum or theatre for debate, conversation and exposition, and so was fighting to break through the blanket of deafness that the system uses against the people who are seeking the truth from a state that does not wish the truth to be revealed. The Irish government hoped that by putting her behind bars the whole embarrassing matter would be out of the press and out of the view of the public, but they were wrong: in daring to take on the state from behind prison walls Margaretta D’Arcy managed to expose war as an obscenity.