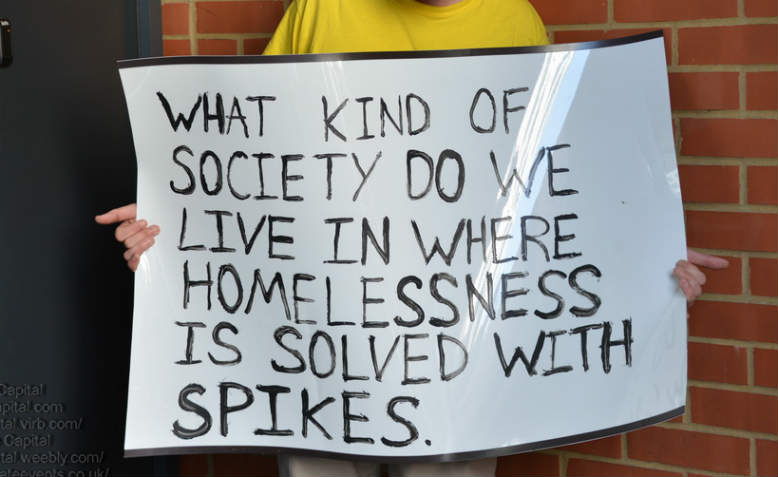

Placard from protest against anti-homeless spikes outside apartments in London, June 2014. Photo: Flickr/See Li

Placard from protest against anti-homeless spikes outside apartments in London, June 2014. Photo: Flickr/See Li

The Tories are responsible for the huge growth in homelessness and rough sleeping, it’ll take systemic change pushed from below to solve it argues Daryl Peach

It’s difficult to fathom how any person living in the fifth richest country in the world can end up in a situation in which they have no choice but to sleep rough on the streets each night, and beg strangers to spare some pocket change in order to survive.

Yet, if you take a walk down any high street in the UK today, this is exactly what you will encounter – men and women that the system has completely failed and abandoned.

Staggeringly, the number of people finding themselves in this situation has increased by 169% since 2010. On any given night, it has been estimated that around 4,751 people will be sleeping rough on the streets of Britain.

What’s worse than the increasing number of homeless is the increasing number of people who are dying as a result.

Since 2013, there have been more than 300 people who have died while living in these conditions- an average of at least two homeless deaths each week. The average age of these people when they died was 43, nearly half of the life expectancy in the UK.

Earlier this year, in being pitted against the sub-zero, arctic weather conditions that engulfed the country; many of those who were unfortunate enough to be without adequate shelter literally froze to death on the street.

In grim contrast to these figures, over the same time frame, there were more than 11,000 empty homes on the market which were kept vacant… for at least 10 years.

This is nothing less than a total indictment of how our society operates: priorities are cast aside to appease those with wealth, even if it causes unnecessary deaths as a result.

Successive governments, in fully embracing free-market fundamentalism, have washed their hands of the idea of social responsibility and have left it to individuals and charity to pick up the pieces where the system so massively fails.

While these well-meaning groups provide an invaluable lifeline to those in need – the unfortunate side effect is that they also provide an invaluable lifeline to the government by alleviating them from responsibilities that ought to be managed within.

More recently, the government passed the Homelessness Reduction Act as a way of tackling the problem of homelessness. This makes it the legal duty of local councils to help those at risk and to find accommodation. But while well being well received for some of its efforts, the policy has been criticised for not addressing the root causes of the problem.

As a direct result of austerity, the Tories succeed in making matters worse for everyone involved in the most serious way.

When we consider that homeless people are nearly twice as likely to experience mental health problems when compared to the wider population and that they are nine times more likely to take their own life; it’s easy to recognise the government’s contribution to the rise in deaths in this community by acknowledging the cuts that have been made to well needed public services, such as that of mental health support.

The government’s ideological aversion to the building of more affordable social housing (currently at its lowest numbers since records began) also plays a fundamental role in enabling this problem to exist. This, combined with the barrage of low paid and insecure jobs, cuts to welfare and rising rent to private landlords make for a vicious, ongoing scenario.

As for those who do wind up on the streets, they have a reduced number of beds in homeless shelters to fight over.

With all of this unfolding, parts of the public fixate on the visible problems contained within the homeless community and assert the idea that they are a type of subhuman underclass; a culmination of alcoholics and drug addicts who are totally to blame for the situation in which they are in. Of course, It doesn’t aid matters when councils run poster campaigns in high streets that feed into this narrative and help cement the idea into public thinking.

Adherents to this close-minded argument would do well to consider that the wealthiest, upper class in society also have problems with addiction and drugs. The difference here is that they live away from familiar streets and have the luxury of being able to pay for private help if they so wished. This same help, of course, is unattainable to those who can’t even afford a cup of tea.

Any way you look at it, it is widely acknowledged that being homeless increases substance abuse significantly – and in all cases, not having a permanent home causes severe stress and countless practical difficulties that are very hard to overcome under any circumstance.

In solving this problem altogether, these contributing causes have to be addressed at the root. The construction of affordable social housing is absolutely necessary, but at the same time, immediate measures should be taken for those already suffering.

If we believe in the importance of a home as being a fundamental human necessity and a right, it cannot be justifiable that thousands of them remain empty while so many are in desperate need. In order to provide immediate shelter for these people, requisitioning such properties for social use is surely the logical conclusion – certainly under emergency situations in which people are likely to freeze to death.

Similar measures were employed by the government during the second world war, during which time, country houses were turned into hospitals, schools, maternity units and command headquarters. Incidentally, other spaces could have been used to house the residents of Grenfell Tower following the disaster which destroyed their homes – more victims of the consequences of austerity, with many still living in hotels after an entire year.

In this instance too, telling of the current status quo, the response from the community, charities and well-meaning individuals has dwarfed that of the government in picking up the pieces of a failed system – one which the Tories defend so rigorously.

While rough sleeping on the streets is the most visible representation of being homeless, it should always be remembered that the majority of homeless people are out of sight – including over 120,000 children – who are not sleeping rough on the streets, but rather, they are living in inadequate, temporary accommodations – all subject to the stresses, health and sociological detriments of not having a permanent home.

We cannot and should not rely on charity to deal with this problem in our society. Pressure must be directed towards the government and wider establishment to enforce real change, for the alternative to systematic change stemming from below will certainly be more of the unnecessary deaths stemming from the top.