Alice Wheeldon was an anti-war activist during World War I who was unjustly imprisoned by a vindictive and repressive government, writes Jacqueline Mulhallen

Sheila Rowbotham, Friends of Alice Wheeldon by Sheila Rowbotham (Pluto Press, new edition 2015), xvi, 224pp.

Friends of Alice Wheeldonby Sheila Rowbotham is two books in one. The first half (pp.2-109), entitled Rebel Networks in the First World War consists of some essays on the background to the case of Alice Wheeldon, tracing the links between socialists, suffragists and pacifists. Currently, these are perhaps better known about, but at the time of the book’s original 1986 publication this may not have been the case. The second half is a play script, Friends of Alice Wheeldon (pp.113-35), which has the effect of making the first half appear to be extended programme notes. The book has been revised to include new information about Alice Wheeldon and her family.

Over the last thirty years we have lost the activity of staging plays on political issues in working-class venues such as pubs and community centres, since the small touring theatre companies which performed such plays have collapsed through funding cuts, cuts made first to the left-wing companies. In 1980 it was perfectly possible for a left-wing theatre company to tour this play about an injustice committed by the government in 1917 to a number of venues around the country with a cast of eleven, a director, a music arranger, a lighting designer, a designer, a stage manager and two costume and property assistants. And after the play, there was a discussion with an audience who could argue about the political issues in the play. No wonder Maggie Thatcher’s first cuts were to political theatre.

In late 1916 or early 1917, Alice Wheeldon. a left-wing middle-aged woman who was against the war, was arrested for ‘conspiring’with her daughters, Hettie Wheeldon and Winnie Mason, and her son-in-law, Alf Mason, to murder the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, and a member of his Cabinet, the Labour leader, Arthur Henderson.

Before the 1914-1918 war, the Liberal government had faced the Great Unrest, as the activity of the trade unionists was called, increased militancy by the ‘suffragettes’(the Women’s Social and Political Union, WSPU) and, in Ireland, where Home Rule had been promised, resentment of its delay by those who wanted Home Rule, and rebellion among the Ulster Unionists who did not. War had postponed both the granting of votes for women and Home Rule, and a potential general strike in September 2014 was avoided since strikes could be seen as hampering the war effort. Christabel and Emmeline Pankhurst, the leaders of the WSPU, offered their services to the government and John Redmond, the Irish nationalist leader, had offered the Irish Volunteers.

Despite the turnaround in 1914, the balance of forces had become problematic again by 1915. The Liberals were now divided over the continuation of World War I and the Liberal leader, H.H. Asquith, was facing a general election. The solution was to form a coalition with the Tories, but discontent grew nonetheless. Conscription was introduced in January 1916. April 1916 saw the Easter Rising in Dublin, and elsewhere peace movements were beginning to grow. The No Conscription Fellowship (NCF) was the brainchild of Lilla Brockway and was founded by Fenner Brockway and others including Catherine Marshall, a prominent member of the National Union of Suffrage Societies (NUWSS). Unlike the WSPU, members of the NUWSS, the Women’s Freedom League (WFL) and Sylvia Pankhurst’s East London Federation of Suffragettes (ELFS) were against the war. In April, Sylvia Pankhurst and others spoke at a demonstration in Trafalgar Square. Then came the Battle of the Somme with its huge loss of life for no material gain. Many Liberals wanted to end the war, but the pro-war politician Lloyd George, a member of Asquith’s cabinet, was supported in his bid for Prime Minister by Tories, including F.E. Smith, an Ulster unionist who became solicitor general and then attorney general, and was involved in the Wheeldon trial.

Alice Wheeldon had been a member of the WSPU but had parted company with them over the issue of the war. Her daughter, Hettie, was the secretary of the Derby branch of the NCF and Alice herself was one of its supporters, as were Winnie and Alf Mason. Alf was a chemist and they lived in Southampton where they were concealing Alice’s son, William, a member of the NCF. In late 1916 Alice feared for her son and son-in-law. Some conscientious objectors (COs) were being sent to the front and shot as deserters, others were tortured, and 73 COs died as a result of their bad treatment in camps. Understandably, Alice hated Lloyd George and viewed Arthur Henderson, the Labour leader who had joined his Cabinet, as a traitor to the Labour Party.

Alice had connections in the Independent Labour Party (ILP) through Reuben Farrow, secretary of the Derby ILP and also a pacifist, and to the Socialist Labour Party (SLP), through John S. Clarke, editor of the SLP paper who had moved to Derby after his activity in the shop stewards’movement in Glasgow had led to his deportation. Later the connection came through Willie Paul, who financed the paper. Alice ran a second-hand clothes shop and had advised Paul when he wanted to set up a similar stall. Both Alice and Hettie took the Daily Herald, edited by George Lansbury, later the radical leader of the Labour Council in Poplar. They knew Sylvia Pankhurst, who described Alice as a ‘hard-working, kind-hearted, generous woman’. Although Alice was the kind of person that was ‘the backbone of any movement’, according to Sylvia she had not undertaken any ‘serious militancy’–i.e. no arrests, no hunger strikes (p.2).

Meanwhile the government wanted to disband a not very effective spy ring, PM2. One of its members, Herbert Booth, sent a spy to Derby, ‘Alex Gordon’. His real name was William Rickard. Gordon presented himself as a CO on the run, and had a letter from Arthur McManus, a prominent member of the SLP who had been very active in setting up the shop stewards’movement in Glasgow which PM2 was investigating. McManus, like Clarke and Paul, had been banned from Glasgow. Gordon had posed as a socialist to McManus and in fact before the war had been a member of the British Socialist Party (BSP).

Gordon was given hospitality by Reuben Farrow and by Alice the following night, 27 December 1916. The following day he reported to Booth that he had uncovered a plot to kill Lloyd George and Henderson. The day after, Booth arrived. Alice had in fact sent for poison from Alf Mason, who had sent some phials of curare, but she believed that this poison was to kill guard dogs at an internment camp for COs. The aim was to enable Booth and Gordon to release prisoners who they said they could get out of the country. Alf believed this too. In a covering note, he said ‘I pity the dog’. However, Booth and Gordon claimed that the plan was to kill Lloyd George and Alice was arrested.

A weakness in Rowbotham’s book is the lack of detailed factual background such as precise dates or a detailed account of the trial. Quite how these conspirators were actually to get near their proposed targets from Derby is not at all clear from either half of the book. One suggestion as to how Lloyd George was to be killed was by poison dart from a blow pipe to be shot by someone concealed behind bushes at Walton Heath Golf course (p.80). Rowbotham quotes a letter (p.69) from Arthur Lee, brother of the head of PM2, saying that ‘on February 2nd, a plot was discovered to murder Lloyd George by shooting him with a poisoned dart, from behind some bushes, when he was playing golf at Walton Heath’. In this case, the ‘miscreants concerned were Sinn Feiners’. There is nothing to suggest Alice and her family were ‘Sinn Feiners’, but Rowbotham does not make it clear whether Lee was referring to them, or whether another plot was uncovered, or whether it was a popular idea at the time to murder Lloyd George with a poison dart while he was playing golf. In any case, it seems an assassination was very unlikely to succeed.

The family were convicted on the word of the government spy, ‘Alex Gordon’who was not present in court to testify against them. To bring him into court would have risked revealing that he had a criminal record, a history of mental illness and had spent time in Broadmoor Prison two years earlier, which would have made him an unreliable witness. Another spy, De Valda, thought him suspicious. Basil Thomson, Metropolitan Police Commissioner, believed Gordon might have invented the poison dart story or ‘put the idea into the woman’s head’or offered to act as the ‘dart thrower’(p.80).

Yet in the end Thomson consented to use Gordon’s evidence as there was ‘no alternative’(p.81). F.E. Smith, the prosecutor for the State, was determined to succeed with the case. Rowbotham says that at the trial he also ‘wafted into the air’suggestions that the poison could be used ‘in bread’or a ‘poisoned arrow shot from an air gun’(p.60). Booth said that Alice had told him of a suffragette plot to kill Lloyd George by a poisoned nail in his boot, which Alice denied and so did Emmeline Pankhurst. The WSPU did not attack people, though there had been a suffragette arson attack on Lloyd George’s house, which might have suggested the connection.

The jury seemed to swallow this ‘evidence’despite Alice’s denials and her explanation for what she believed the poison was to be used. Smith described Alice and her daughters as ‘using language of the most obscene and disgusting character’and portrayed them as subversive, atheists, feminists and socialists, which they freely admitted they were. Alice admitted in court that she had said that she hated Lloyd George and wished him dead. Yet, as many of us in the peace movement today would confirm, there is a big difference between carrying a placard saying ‘Tony Blair, we know where you live’and actually assassinating a Prime Minister.

Alice was sentenced to ten years in prison, Alf to seven and Winnie to five. Hettie was not convicted, but returned to Derby to campaign for her family’s release. The family appealed, but their appeal was refused and they went on hunger strike. Not quite a year later, Alice was released because her health was weak, and in February 1919 she died in the influenza epidemic which followed World War I. Winnie and Alf were also released long before their sentences were completed. This suggests that the authorities knew that the case was flawed.

The case is reminiscent of the use of ‘Oliver’and other government spies at a time of severe repression one hundred years earlier. Oliver was a notorious agent provocateur whose reports ensured the execution of radical working-class opponents of the government, Jeremiah Brandreth, William Turner and Isaac Ludlam. Later, another agent provocateur, Edwards, encouraged Arthur Thistlewood and William Davidson, among others, to plan the assassination of Lord Harrowby and cabinet ministers at a non-existent dinner in 1820. But there is one big difference. Brandreth, Turner and Ludlam wanted to join a rising, and Thistlewood and his comrades were willing to assassinate the ministers. Alice Wheeldon and Alf and Winnie Mason may have hated Lloyd George but the only evidence for their wish to murder them is the testimony of Booth and Gordon. The government continues to use spies among activists as the case of Mark Kennedy shows.

PM2 was disbanded. They could not use Booth or Gordon again. Glasgow shop stewards supported Alice and her family and W.C. Anderson, Labour MP for Sheffield, began an enquiry into Gordon. Gordon was sent to South Africa, and on his return after the war he apparently worked as an industrial spy.

Hettie married Arthur McManus, gave birth to a stillborn child and in 1920 died from peritonitis. Arthur became the first President of the British Communist Party. William Wheeldon went to Russia with Quaker famine relief, stayed on and became a victim of Stalin’s purges. Winnie died in 1953 and Alf in 1960, but Chloe and Deirdre Mason, their grandchildren, are campaigning to clear the namesof their grandparents and great-grandmother. The historian Nicholas Hiley has done a great deal of research into this case over the past thirty years.

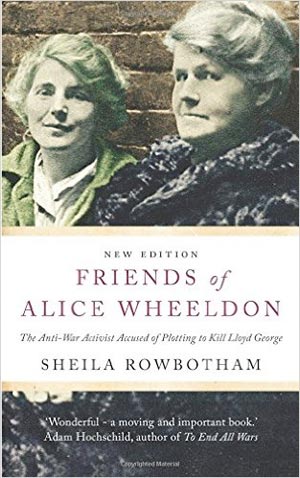

No doubt for these reasons, Rowbotham decided to revise and republish the book, but it was presumably in some haste since there are a few errors. On page 182 of the play script, two speeches are repeated, and on page 178 a speech by ‘Jessie’is incorporated into the preceding one by ‘Arthur’. On page xv of the introduction, a reference to Alice Wheeldon’s husband as William Augustus Marshall should have read William Augustus Wheeldon. Marshall was Alice’s maiden name. It is also a pity that the cover illustration has split the photograph of Alice, her daughters and a prison guard to show Hettie and a prison guard on the front cover with Alice and Winnie on the back. It was not until after checking with the Alice Wheeldon website that I realised this, and I think others may be misled into thinking that the prison guard is Alice!

The case of Alice Wheeldon and her family is an important one for many reasons. It explodes the myth that the people of Britain were united behind the government in grim determination to obtain absolute victory over Germany. It exposes the lengths the supposedly liberal British state has taken to suppress and persecute peaceful dissent. The case therefore gives the lie to the idea that World War I was being fought to defend liberal democratic values. It deserves to be much better known.