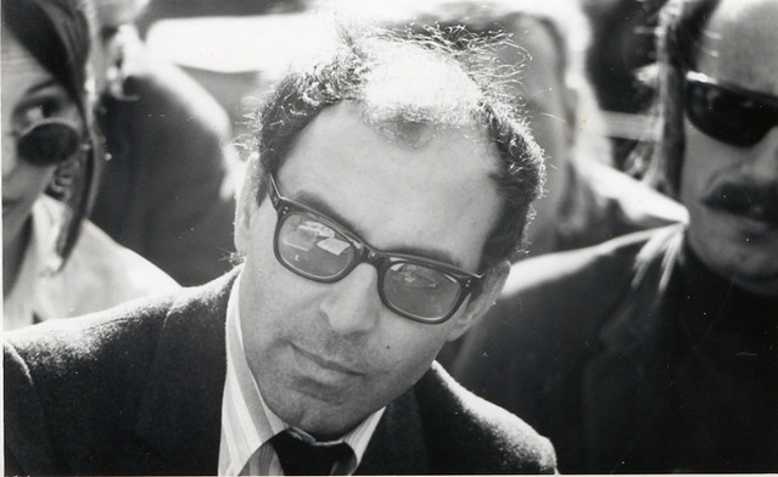

Godard at Berkeley, 1968. Photo: Gary Stevens/cropped from original/licensed under CC2.0, linked at bottom of article

Godard at Berkeley, 1968. Photo: Gary Stevens/cropped from original/licensed under CC2.0, linked at bottom of article

Cinephile, writer, filmmaker, revolutionary: Martin Hall discusses the work of Jean-Luc Godard, who has died

“A story should have a beginning, a middle and an end, but not necessarily in that order.”

Jean-Luc Godard, who has died aged 91 following an assisted suicide procedure, did more than any other post-war filmmaker to redefine narrative cinema. From the release of his first feature À Bout de Souffle in 1960, which helped kickstart the Nouvelle Vague, to his final 2018 film, Le Livre d’image, he continued to ask the same question: what is cinema?

Of course, he didn’t just make films: he wrote about them for Cahiers du Cinéma and other publications, made work for television, composed a history of cinema and, crucially, threw himself into revolutionary politics and the French Maoist ferment of 1968.

First and foremost, though, he was a cinephile. Indeed, the subtitle to Peter Bradshaw’s tribute in The Guardian, ‘a genius who tore up rule book without troubling to read it’, is quite wrong. He loved (and at the same time didn’t love) Classical Hollywood cinema, and at least his first 11 films up to and including Masculin Féminin (1966) are to a significant degree takes on the genres codified by the Fordist mode of production of the American cinema of the 1920s and ‘30s: the musical; science fiction; the gangster film and melodrama.

By working within genre cinema but throwing out its narrative and formal rules through the use of jump cuts, non-diegetic inserts, direct address to camera and other innovations, he took a dialectical approach to the question of filmmaking. Even at this early stage, though, there are signs of what is to come: the interrogation of revolutionary struggle in Le Petit Soldat (1963[i]) set in the Algerian war for independence. Moreover, there is the constant questioning of the efficacy of the feature film form, often through intertitles, a device of course associated with the silent film.

In Masculin Féminin, this dialectic is shown through the intertitle, ‘the children of Marx and Coca-Cola’, which he uses to refer to the generation typified by the lead character and his circle. It is in this film and in his remaining four features of the 1960s where we see a transition. The dialectic is coming to some sort of resolution in favour of a retreat from the feature film and towards explicitly revolutionary cinema, in both form and content.

He abandoned feature film making from 1967 until 1972, when he returned with Tout Va Bien, which was a film about revolutionary struggle without being a film that is revolutionary in form; at least not compared to the films he had been making in the previous three years. From 1968 until 1971 Godard made films as part of the Dziga Vertov[ii] group, named after the great Soviet filmmaker, mostly in conjunction with Jean-Pierre Gorin, a student, though they were predominantly released without directorial credit.

They are products of the Maoist turn that took place throughout the west, but most powerfully in France, during the period. Indeed, Perry Anderson talks of “a new gravitational force…exercising a tidal pull on the Western Marxist culture of the late sixties and early seventies[iii]”. There isn’t space here to discuss fully why this happened, but briefly, the taking up of Maoist ideas in France created a useful line of division with the Communist Party, which was aligned with Moscow, and increasingly seen as reformist after Khrushchev’s reforms of the late 1950s and early 1960s. Furthermore, the Trotskyist and Maoist left both critiqued Stalinism as a bureaucracy that had turned the revolutionary situation in Russia into a form of state capitalism, and the Cultural Revolution in China was seen as a method of returning revolution to states where those tendencies had taken over.

Godard was very much part of this turn. To give one concrete example: he was involved in shutting down the 1968 Cannes Film Festival in May – an action that was part of the revolutionary struggle happening in Paris and throughout France. He also made an uncompleted film about the Palestinian struggle, which also appears as a thread running through his later films, and directly addressed the Vietnam War.

The Dziga Vertov films deal with concrete political issues of the day and are also theoretical investigations. If we could sum them up with one phrase, it would be this, which comes from Jean-Luc Comolli and Paul Narboni’s 1969 Cahiers du Cinéma essay, ‘Cinema/Ideology/Criticism[iv]’:

“the film is ideology presenting itself to itself, talking to itself, learning about itself.”

That remained true even when he returned to feature filmmaking.

Despite often referring to it as a secondary form, he made work for television from 1968 onwards, and from the mid ‘70s filmed for the small screen a lot, often in conjunction with collaborator, Anne-Marie Miéville. Indeed, despite his reputation as an auteur, he was in many ways always in collaboration, be it with actors he used repeatedly, such as Jean-Paul Belmondo and his first and second wives, Anna Karina and Anne Wiazemsky, or the filmmakers already discussed. The politics of authorship were both individual and collaborative for him.

He also made an archive of the cinema, Histoires du Cinéma (1988), nominally a feature film, but running to four and a half hours. In it he asks what effect film had on the 20th century, what effect the times had on film, and what the image is. He would continue this investigation in his final films from Éloge de l’amour (2001), through Film Socialisme (2010) and on to his last feature mentioned above. The 2001 film uses black and white film and colour digital video to think about memory, the war, collaboration, refugees, the Holocaust and, as the title suggests, love.

Then there is his feature filmmaking from the end of the seventies and through the eighties, known as the Second Wave, which introduced a new generation to his work. But, of course, it is the films of the 1960s for which he will be remembered the most. Those 15 features, made in just 8 years, reinvented the language of cinema. Without them, there would be no New Hollywood, no Lars von Trier, no Quentin Tarantino; or if they existed in a world without Godard, they would be markedly different. The cinema is a less exciting place without him.

[i] The film was shot in 1960 and banned by the French government as it accused it of participating in torture

[ii] The name means ‘spinning at great speed’ and – Vertov was born David Kaufman

[iii] Perry Anderson, In the Tracks of Historical Materialism (London: Verso, 1983) p. 72

[iv] Jean-Luc Comolli & Paul Narboni, ‘Cinema/Ideology/Criticism’. Screen, Volume 12, Issue 2, 1 July 1971, P. 145–155

Join Revolution! May Day weekender in London

The world is changing fast. From tariffs and trade wars to the continuing genocide in Gaza to Starmer’s austerity 2.0.

Revolution! on Saturday 3 – Sunday 4 May brings together leading activists and authors to discuss the key questions of the moment and chart a strategy for the left.