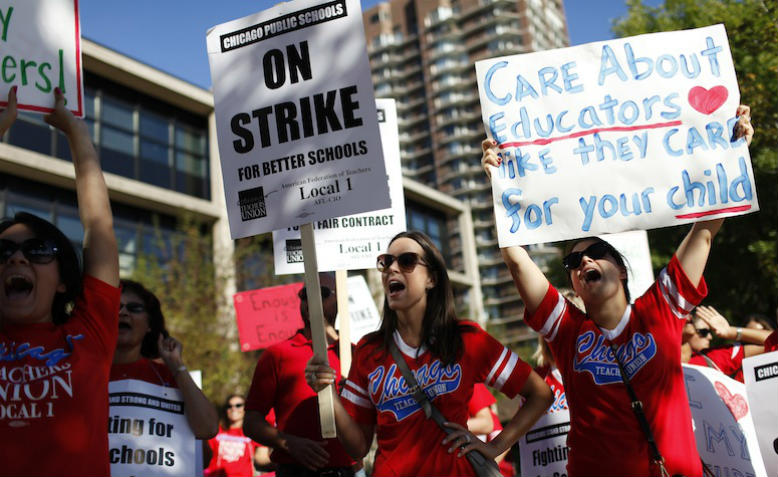

Chicago Teachers' Strike 2012. Photo, TMT via flickr

Chicago Teachers' Strike 2012. Photo, TMT via flickr

Teachers in Chicago are building on the successes of 2012 to create an inspirational campaign and win important victories, reports Kate O’Neil

This week, an overwhelming majority of the 25,000 members of the Chicago Teachers Union (CTU) voted to ratify a new collective bargaining agreement with the Chicago school board, following a two-week strike that ended on 1 November. The five-year deal, which was approved by 80% of members, signals for the first time a reversal of austerity in Chicago’s state schools. It includes a sector-leading 16% pay rise for teachers and a whopping 40% pay rise for support staff; $35 million in funds per year and unprecedented enforcement mechanisms to reduce class sizes; and a commitment to put a nurse and a social worker ‘in every school every day’ by 2023. Although the union did not win all of its demands, it is notable that the agreement contains not a single austerity-era concession.

As with their precedent-setting 2012 strike, the CTU has set a new standard for what teaching unions can achieve through collective bargaining. One of the key innovations of 2012 was the demand that the school board address issues beyond the purview of teacher pay and conditions—racial segregation, poverty, privatisation and inadequate funding in schools. This innovation was introduced by the union’s left-wing leadership and had its roots in a principle of organising developed in the 1980s and 1990s, known as social movement unionism.

Social movement unionism represented a move away from closed-door contract talks between union leaders and employers around a narrow set of workplace demands (a practice known as ‘business unionism’), and a move towards more lay member and community involvement and the advocacy of wider social change. Indeed, the 2012 strike was as well known for its broad set of demands as it was for its ‘movement feeling’: widespread support from the public and mass pickets and demonstrations by teachers, students and parents. It is credited with providing a model for teachers’ strikes ever since, most notably the wave of ‘red state revolts’ in West Virginia and other southern states in 2018 and the Los Angeles teachers strike last January.

Each of these strikes broke new ground in the teacher union movement, but they were primarily defensive in nature. The 2012 Chicago strike, for example, began as a fight to ward off attempts by then-mayor Rahm Emanuel to introduce a longer school day with no additional pay and tie teacher evaluations to test scores. It was waged in the context of a decade-long school closure and privatisation campaign in the city’s state school system and was the first CTU strike in 25 years. While the ‘red states revolts’ brought illegal and state-wide strikes onto the scene, and extended the movement to more conservative parts of the country, they were launched to fight cuts in salaries and benefits. The LA strike, also led by a left-wing union, brought a socially conscious struggle to the nation’s second largest school district and won some demands which prefigured those won in Chicago this week. But their strike was their first in thirty years, and to get the ball rolling they had to contend with a vicious anti-union media campaign by the schools superintendent and a billionaire-bankrolled plan to privatise half the school system.

This latest strike by Chicago teachers stands out because it is the first time in decades that a teachers’ union has fully gone on the offensive. How was this possible? Both objective and subjective factors were key.

First, unlike 2012 in Chicago or Los Angeles in 2019, the CTU did not have to face off against a pro-austerity, pro-privatisation mayor or superintendent. The mayor, Lori Lightfoot, is a progressive Democrat who was elected in February with a transformative programme for schools: an elected school board; investment in neighbourhood schools; adequate staffing of nurses, counsellors and social workers; a moratorium on charter school (academy) expansion; and an overall redress of racial inequalities within the system. The platform so closely mirrored the union’s own vision that one teacher activist quipped, ‘If she had been a student, I would have accused her of plagiarism.’ Furthermore, Chicago state schools had just received $1 billion in additional funding from the state government and could hardly be expected not to invest it. Thus, what was at stake was not whether attacks on teachers and state schools would be carried out, but whether the promise of reform would actually be fulfilled.

Secondly, the union, led by a now well-seasoned left, consciously organised according to a set of tenets developed within the American labour movement in the years since the 2012 strike, called Bargaining for the Common Good. Drafted at a conference of leading trade union activists in Minneapolis in 2014, it builds upon the broad notions of social movement unionism to devise strategies for how to win social demands specifically through union contract negotiations. Joseph McCartin, a labour expert who helped organise the conference, explains that

the Minneapolis gathering was more than simply another iteration of an oft-repeated union tradition. It represented something new, a conscious effort to tie union-community mobilization to the function that lies at the very heart of unionism: collective bargaining.

The tenets highlight the need to: ‘go on the offensive’ in negotiations; ‘expand the scope’ of contract demands to win gains for the wider community; ‘deeply engage’ the membership in organising; and engage community allies ‘at all stages of the campaign’. Teachers unions across the US have been organising according to the principals of Bargaining for the Common Good for a number of years now, but according to McCartin, the recent Chicago strike was in many respects “both the toughest and most visionary strike fought yet” to put it into practice.

Going ‘on the offensive’ in the Chicago context meant that the union did not sit back and wait for the mayor to follow through with her promises after her election. Instead, the CTU seized the initiative by drafting a list of concrete proposals to carry out the mayor’s reforms and publicly challenging her to agree to them in writing. This was critical to the strike’s success. Lightfoot proved she could not be trusted to follow through on her promises and refused to budge on any issues apart from teacher pay for ten months leading up to the strike. This allowed the union to both set the terms of negotiation and put Lightfoot on the back foot by exposing her hypocrisy in the media. Not only did more Chicagoans support the teachers than supported the mayor or school board, far more actually said they would blame the mayor and school board for a strike. CTU member Brandon Johnson summarises how the union gained the ideological upper hand.

We’re spending billions of dollars in development for the wealthy to have playgrounds in some of the wealthiest parts of the city, but we don’t have a nurse and a social worker in every school? I mean give me a break…It’s possible to find and generate revenue for everything else that people have placed as a priority. And so we are forcing the conversation in this fight, and we’re making the families who have been at the margin of that agenda… the priority of this political season.

Lightfoot justified her stonewalling in negotiations by pointing to a 1995 state law, which states that the Chicago school board is not required to bargain over issues that do not directly pertain to staff pay and conditions. Thus, to win gains that would affect their students, the CTU needed to force the school board to ‘expand the scope’ of contract demands. They did so by breaking with tradition at the bargaining table. The pay package the teachers agreed to this week was actually offered by the school board well before the strike and will make Chicago teachers some of the highest paid in the country. But rather than walk away with a good deal for teachers, the CTU strategically held out on teacher pay until the board agreed to its other key demands.

And the union was able to win more with this strategy than they did in 2012. Seven years ago, the union settled for some verbal commitments on class size and staffing which never came to fruition, but this time around they refused to back down until guarantees were inscribed in the contract. Furthermore, whereas in 2012 Chicago teachers were only able to raise awareness about social inequities beyond the classroom, this year they were actually able to win demands at the bargaining table to address them. For example, the union won a ‘sanctuary schools’ clause for immigrant communities, which prohibits immigration enforcement agents from entering school premises without a warrant. To address the housing crisis in poor communities, they also won a commitment to hire full-time ‘homeless coordinators’ in schools with high numbers of homeless children.

But none of these would have been won without a strike that leveraged a ‘deep level of engagement’ on the part of the union membership. Teachers had been rallying and preparing for a strike all year and were ready and confident for a fight. ‘They expected to win,’ explained CTU chief of staff Jen Johnson. Members, students, parents and allies turned out en masse to picket lines each morning at their schools, and demonstrations in the city centre in the afternoon were every bit as spirited as those that captured the imagination in 2012. In the end, it was this that forced Lightfoot’s hand. ‘We got more done in the first two days of the strike,’ explained CTU bargaining team member Quentin Washington, ‘than we did out of ten months of negotiations.’

The union also blazed new trails in the teachers movement nationally by striking jointly with SEIU 73, the union representing the 7,500 support staff in Chicago schools not represented by CTU. The mass demonstrations in downtown Chicago, once dubbed a ‘sea of red’ in the media in reference to the teachers union colours, have now been called a ‘sea of red and purple’, to take into account the presence of purple-shirted janitors, bus aides, park workers and teaching assistants. Joint workplace action raised new possibilities for the prospect of engaging allies ‘at all stages of the campaign’ and gave the feeling of a more generalised working class rebellion in the city. ‘1% of Chicago is on strike,’ was an oft-cited statistic by activists.

This feeling was reinforced by a constant flow of activity throughout the city for the duration of the strike. Strikers were not simply cheerleaders for their bargaining teams. They organised and attended ‘fringe’-style meetings and actions where a wide range of issues related to the strike and the broader movement were raised. These often involved building solidarity with other unions, civil disobedience or protests of property developments built with public funds (called ‘TIF’s) that should have been used for schools. A selection of calendar postings e-mailed to members each day of the strike gives a sense of the ‘festival of resistance’ atmosphere:

Monday, October 21

Morning pickets

Regional unity marches

Youth action at City Hall to demand a $15 minimum wage and a fair contract teachers

R3 Coalition teach-in for strikers on community-based struggles

Grassroots Collaborative art build

Tuesday, October 22

March through the Pilsen neighbourhood

Rally in the Logan Square

Solidarity meeting with Triton Community College workers

Solidarity meeting with AFSCME Local 1989 at Northeastern Illinois University

‘CTU/SEIU Strike: What the Media Isn’t Saying’, a forum for the Latinx community

Thursday, October 24

Morning pickets

Neighbourhood canvassing

Civil disobedience training

Sunday October 27

Rally at New Mt. Pilgrim MB Church with civil rights leader Rev. Dr.William Barber II

Monday October 28

Morning pickets

Youth-led march and sit-in at City Hall

Tuesday October 29

Protest at the Lincoln Yards TIF development

Solidarity Road Trip for Decatur Teacher Assistants

As with any contract fight, the union did not win everything it asked for at the bargaining table. They did not win a prep period each day for primary school teachers, and the mayor only agreed to make up five of the lost eleven school days from the strike. Moreover, the long duration of the agreement, five years, is not viewed as advantageous to the union, as they are not permitted to strike over matters not related to collective bargaining.

Nonetheless, the Chicago teachers have once again shown the world how to fight neoliberalism with a picket sign in one hand and a list of contract demands in the other. And the gains they have won this time are not just demonstrating how to stand up, but how to march forward.

This invites the question: what lessons can teachers unions here learn from this strike? Can ‘Bargaining for the Common Good’ principles be applied to fight chronic underfunding and teacher shortage in schools in England? The answer is not so straightforward.

The National Education Union (NEU), the largest teachers union in the UK, benefits from a progressive leadership which took inspiration from the 2012 Chicago strike and consciously follows the principles of social movement unionism to this day. They have built a strong relationship with the CTU and have organised a number of successful campaigns with community allies which challenge racism, over-testing, school funding cuts and other injustices in education and beyond. But the NEU only represents a section of the teaching workforce in England. In any given school, teachers may belong to a range of different unions or remain completely unaffiliated. This is very different from the model in Chicago and elsewhere the US, where all the teachers in a school district belong to a single union.

Moreover, since the 1980s teachers in England have not bargained collectively with state authorities. Decisions on pay and conditions are determined by an unaccountable pay review board, the School Teachers’ Review Body (STRB), whose recommendations to the government are in any case non-binding. In theory, unions could press local councils for reforms, but the majority of secondary schools and roughly a quarter of primary schools are now privately-managed academies, where salaries and conditions are decided at the school level.

Finally, there are historical differences in organising strategy as well. Longer all-out strikes–which have been the centrepiece of teacher combativity in the US– do not characterise teacher organising in England. Even calling for a strike has its particular obstacles. In both Chicago and England anti-labour laws require high thresholds of union members to vote for strike action, but Chicago teachers have been able to exceed these thresholds by balloting at the workplace–a right teachers in England do not have.

Every union needs to weigh the pros and cons of a strategy in its specific context, and the strike’s lessons may not be as easily transferrable between Chicago and London as they are between Chicago and LA. But it is time to begin considering the benefits, and possibly the necessity, of all-out strikes in order to beat back austerity in England’s schools. It is hard to imagine that what was achieved, both at the bargaining table and in the hearts and minds of the working class in Chicago this past month, could have been accomplished through a one-day strike or partial strikes at certain schools. Longer all-out strikes are not without risks, but there is nothing like a halt to business as usual to educate the public about the deep crisis in schools we face today–and educate teachers and communities about how to fight together and win. You never know. We could even win the right to bargain collectively.

Kate O’Neil is a former activist in the Chicago Teachers Union and now teaches in London where she is a member of the NEU.