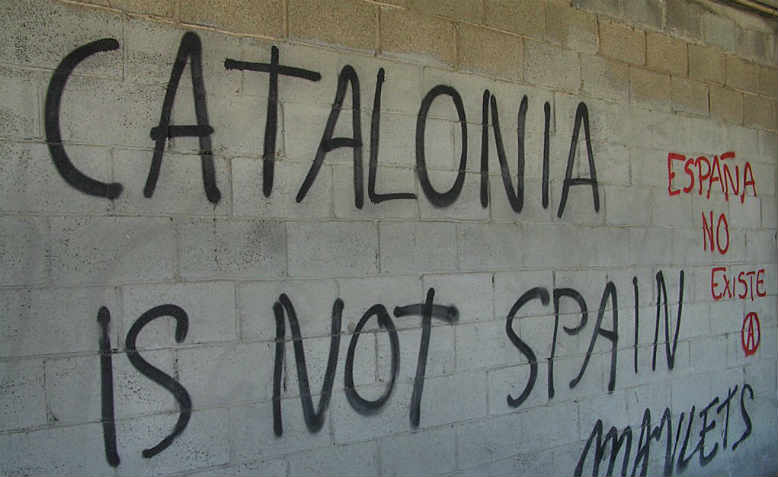

Barcelona graffiti from 2008. Photo: Barcalunacy photoblog

Barcelona graffiti from 2008. Photo: Barcalunacy photoblog

Democracy and the national question are pivotal issues in today’s Europe, argues Lindsey German

One of the lessons about the Spanish government’s repressive and arrogant behaviour over Catalonia is that we should never take the commitments to equality of those who rule over us too seriously. There is after all the right to self-determination of peoples, the right to national independence, the right to speak one’s language, all enshrined in various international agreements and laws. All this is just junked by the right wing Spanish government which declares the indivisibility of the Spanish state and that any national secession is unconstitutional. This behaviour is totally endorsed by the EU leadership, which declares the vote by the Catalonian parliament for an independent republic as illegal.

The central government – run by a right wing with its roots in Franco’s Spain, which sees the centralised state and monarchy as key to its political project – has now threatened imprisonment of political leaders (with two already in prison) and police in Catalonia, a return to direct rule, and elections in December, from which it appears pro-independence parties will be barred. The British government has fully backed the Spanish prime minister Mariano Rajoy in this, as has the EU. Jean-Claude Juncker has made clear that he will do everything to back the Spanish state, saying that the 28 states can’t have any more fragmentation or separation.

It isn’t really up to him to set himself up as arbiter of this question especially when the EU and its major powers have been so keen on breaking up countries in other parts of the continent. In fact, the right to self-determination is a right, not an option to be bestowed by governments. I noticed on Saturday that the embassy for the independent Republic of Kosovo, part of the former Yugoslavia, is still considered by the UN as part of Serbia. It is however recognised by 111 states, despite the wishes of the Serbian government. Germany, in particular, encouraged the break up of Yugoslavia and Czechoslovakia in the early 1990s in order to strengthen support for a pro-western agenda.

The determination of Spain’s right to maintain the unity of the state and to crush the nationalists is directly in contravention of national rights and stands very strongly in the tradition of Franco and all he represented.

Given this background, the left should be a little more clear on the issues and a little bit more forthcoming with solidarity for the Catalans who are taking a brave step, and doing so against a repressive Spanish state. It isn’t even a question of whether or not you support independence but whether the Catalans have the right to decide this. To support Catalonia now is to defend the choice that people should have about how they are governed. I don’t really understand why this is not more widely understood, and why, in particular, Labour doesn’t make a tougher stand on all this. I fear that too many of the left, as I said last week, are themselves so frightened of any break up of the EU that they do not want to go down the road of independence. But Europe’s borders are not rigid and have changed a number of times even in the last century. And if the growing nationalism in Catalonia is at least in part a response to economic crisis and lack of accountability of national government, then the left has a responsibility to understand it as an expression of discontent from below and relate to that.

This is important because there are many battles ahead on this question and we know that nationalist leaderships have – to put it politely – a record of pulling back from full confrontation with the state and central government, and may be willing to compromise much more than many of their supporters. Puigdemont was forced to the independence vote by pressure from below. That pressure needs to grow and spread to industrial action, to direct action and different forms of street protest. The Catalan left will face battles not just with central Spanish authorities, but within their own movement. Telling them they should just sit down and negotiate with those who wish them no good really isn’t going to cut it.

The Balfour Declaration: a settlement with empire written all over it

National oppression has a lot of its origins in imperialism and where better to see that than with the British variety? This week marks the 100th anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, where Britain declared its support for the establishment of a Jewish settler state in the Middle East. The date was significant: the First World War was dragging through its third year, and the Russians were to leave that war following two successful revolutions in 1917. The old Ottoman Empire, based in Turkey, but covering much of the Middle East, was collapsing. France and Britain, in particular, were looking at who would control the region and thinking about how they could divide up the spoils once the Ottomans were defeated. Britain’s empire had already received a blow from the Irish Easter Rising in 1916. Its rulers feared growing independence sentiment in India. The need to protect the trade routes to India and the east, the need to maintain control of the Suez Canal in Egypt, and the need to avert revolution in the former imperial colonies, all loomed large in the British minds.

After the war, Britain gained the ‘mandate’ to control and run Palestine. The Palestinians faced growing pressure from the Jewish settlers and there was increasing conflict between them and the Palestinians, especially in the late 1930s. The Holocaust and the persecution of Jews in Europe, before and during the Second World War, led to greater clamour for a Jewish ‘homeland’ and to the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948. This was done at the cost of driving Palestinians off their own land, to such an extent that they still form the largest group of refugees in the world. The 1967 war saw Israel occupy far more territory, which it still holds. Its more recent settlements have further taken land from Palestinians, whose plight is now recognised by millions of people worldwide as one of great injustice.

One of the current arguments about this conflict in Britain is that criticism of Israel is, in fact, anti-Semitic. This argument is used to attack the left, but ignores the fact that Jewish people themselves are divided on the question of Palestine. My great friend and political mentor, Tony Cliff, was born into a Jewish settler family in 1917. His real name was Ygael Gluckstein, the name Ygael, as he told me, being after a Jewish settler hero who had killed Palestinians. He became aware of the treatment of Arabs as a young teenager and was always tremendously in support of the right of Palestinians. He left Palestine after the war because he knew it would become increasingly hard to operate politically in the new state and lived in London, where – unlike much of the British far left – his anti-imperialist politics always informed his practice.

Towards the end of his life, I remember him saying that the situation for the Palestinians was even much worse than he had imagined it would be. He (and many of those who take similar positions today) was denounced as ‘self-hating’, but it is so important that Jewish people, who know so much about being refugees and suffering persecution, are prepared to stand up for the Palestinians and oppose discrimination against them.

The British government’s record then was not about caring for Jewish people – after all the Balfour declaration was little over a decade after Britain had passed the Aliens Act aimed at preventing persecuted Jews from coming to live in Britain. Today, it is about defending its interests in the Middle East.

Justice for Palestine has long been a slogan of the anti-war movement and I’ll be joining the demonstration this Saturday (4 November) to mark the anniversary of Balfour and to say time to make it right for the Palestinians.

Do people really not know what all the fuss is about?

The latest stories about sexism, and attitudes to it, centre on politicians. First, we had Jared O’Mara, recently elected MP for Sheffield Hallam, who was found to have made a number of sexist remarks on social media. His initial apology was accepted but then further revelations have led to his suspension from the Labour whip. Then we had Michael Gove thinking it’s ok to make a joke about rape and assault on the Today programme, which was then embellished by Neil Kinnock – and not challenged by the presenters or presumably the producers until after the show. Then a speech by Jeremy Corbyn saying that these sexist attitudes and behaviour were unacceptable and had to be rooted out of politics. Finally, the revelation about several Tory ministers being accused of sexist or harassing behaviour.

The reaction from much of the media is so what? That includes a lot of national journalists, including some who work in parliament. They don’t know what the fuss is about and shouldn’t people be a little more relaxed about some of this stuff. This is after the Weinstein affair, the Savile affair and the imprisonment of several former BBC celebrities for sexual assault. You would think that might make people be a bit more circumspect about dismissing these accusations, but apparently not.

It is clear to me that sexual harassment, assault and sexism generally exist throughout society, but they are very much connected to questions of power. So, when you work in powerful institutions there is likely to be institutional sexism. This is so obvious in parliament. Most MPs are older men; many researchers and other workers are younger women. I have always thought this makes for a distasteful atmosphere and sometimes worse, as a number of the allegations now suggest. We hear now that Theresa May receives reports about Tory MPs and their sexual behaviour every week. This suggests the place is riddled with sexism. It will take more than a few reforms to sort that out. And minimising its importance does no one any favours. Yes it is there and it’s right to make a fuss.