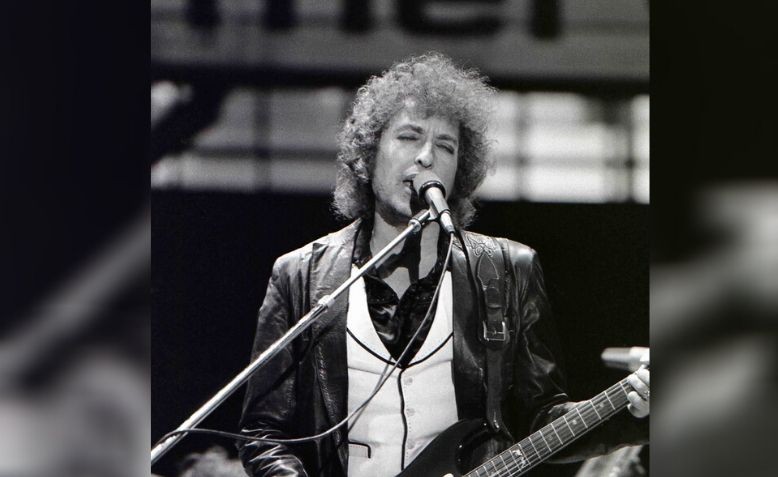

Bob Dylan performing in Rotterdam on 23rd June 1978. Source: Wikipedia

Bob Dylan performing in Rotterdam on 23rd June 1978. Source: Wikipedia

Morgan Daniels reviews ‘Rough and Rowdy Ways’, the latest studio album from Bob Dylan

Fixin’ to die?

The verdicts are in and one of the ideas around which reviewers have coalesced is that Rough and Rowdy Ways represents a deep and sustained meditation on death, possibly the last hurrah of an artist who will be eighty next year. It’s a reasonable enough assumption to make, given that its very first song, ‘I Contain Multitudes’, begins: ‘Today and tomorrow and yesterday too / The flowers are dying as all things do’.

Yet death is no more in evidence on Rough and Rowdy Ways than, say, Dylan’s very first album, released eponymously before he’d turned twenty-one back in 1962. A whole life ahead of him, Bob Dylan on Bob Dylan wrestles endlessly with his own mortality, covering traditional songs like ‘In My Time of Dyin’’ and ‘Fixin’ to Die’, and ending with the Blind Lemon Jefferson number ‘See That My Grave is Kept Clean’. And he sure sings like he’s just about to meet his maker.

By contrast, Rough and Rowdy Bob doesn’t sound too worried about snuffing it. He’s more alive than on Bob Dylan. In ‘False Prophet’, he almost takes a sick relish in lauding it over all those he has outlived:

‘I’m first among equals, second to none

The last of the best, you can bury the rest

Bury’em naked with their silver and gold

Put’em six feet under and pray for their souls’

Even on the slow and weird ‘Black Rider’, which seems to be addressing the Grim Reaper directly, Dylan’s got a trick or two to pull. For sure, he sings, ‘My soul is distressed and my mind is at war’. But as the song comes to a close, Death Itself is told: ‘Black Rider, Black Rider, hold it right there / The size of your cock won’t get you nowhere’. Here’s a life lesson if ever there was one from the 2016 winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature. Perhaps staring down the Reaper with juvenile humour is one of those things you just to learn to do. You can’t imagine 1962 Bob being so cocksure, so to speak, about the prospect of death. He’s younger than that now.

Song and dance man

If Bob Dylan has spent a lifetime singing about dying, does he mean it?

In ‘Goodbye Jimmy Reed’, probably the roughest and rowdiest of his new songs, Dylan drops a line that I take to be the hinge on which the whole album rests. It’s a simple one: ‘I can’t sing a song that I don’t understand’. Put otherwise, Bob Dylan wasn’t bullshitting on Bob Dylan, but was at the beginning of a very long recording career marked by absolute devotion to the history and traditions of popular music. Answering a question on his religious beliefs in a famous 1997 interview with Newsweek, Dylan explained:

‘Here’s the thing with me and the religious thing. This is the flat-out truth: I find the religiosity and philosophy in the music. I don’t find it anywhere else. Songs like “Let Me Rest on a Peaceful Mountain” or “I Saw the Light” — that’s my religion … The songs are my lexicon. I believe the songs.’

I believe the songs.

It’s this belief that has instinctively placed Dylan on the right side of many historical questions, however much he might frustrate on others. His early heroes sang songs of working-class struggle and the fights against racism and war. So did Bob, and even years after he abandoned his ‘folk persona’, he would write songs infused with resistance and a sense of justice: outright protest against systemic racism in ‘Hurricane’; a haunting history of slavery in ‘Blind Willie McTell’; a tale of austerity and exploitation in ‘Workingman’s Blues #2’. (The front cover of Rough and Rowdy Ways, it should be noted, features a 1964 photograph of an underground club predominantly for black people on Cable Street in London.)

It matters greatly, then, that Dylan treats us to a very wide survey of his musical interests on this new record. Over seventy different songs are referenced on ‘Murder Most Foul’ alone. Throughout Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan compares himself to ‘those British bad boys, the Rolling Stones’; borrows Jacques Offenbach’s ‘Barcarolle’ for ‘I Gave Up My Mind to Give Myself to You’; and reworks Billy ‘The Kid’ Emerson’s ‘If Lovin’ is Believin’ in ‘False Prophet’. Even by Dylan’s standards, Rough and Rowdy Ways boasts a wilfully scattergun approach to namechecking and repurposing.

Dylan and the undead

‘The ultimate fantasy would be to write about a fantasy because as soon as you realize it’s fantasy, it changes.’

Michael Taussig, ‘The Beach (a Fantasy)’, 2000

Much more so than death, Rough and Rowdy Ways is surely about death’s opposite—about creation.

Speaking to the New York Times recently in the only promotional interview for his new album, Dylan was asked about ‘When I Paint My Masterpiece’, a song he recorded in 1971. Noting that he had warmed to it recently himself (!), Dylan added that ‘Masterpiece’ was concerned with

‘something that’s out of reach. Someplace you’d like to be beyond your experience. Something that is so supreme and first-rate that you could never come back down from the mountain. That you’ve achieved the unthinkable. That’s what the song tries to say, and you’d have to put it in that context. In saying that though, even if you do paint your masterpiece, what will you do then? Well, obviously you have to paint another masterpiece. So it could become some kind of never-ending cycle, a trap of some kind.’

These words came to mind as I listened to ‘Key West (Philosopher Pirate)’, the stunning penultimate song on Rough and Rowdy Ways. Dylan evokes Key West, a tiny little island in the Florida Keys, as an idyll which will cure almost any problem:

‘Key West is the place to be

If you’re looking for immortality

Key West is paradise divine

Key West is fine and fair

If you lost your mind, you’ll find it there

Key West is on the horizon line’

You reach Key West, and what will you do then? Well, obviously you’ll go someplace else. The Key West of your dreams doesn’t exist and nor does that perfect masterpiece. But you sure as hell have no option but to keep on travelling and to keep on writing. ‘You always have to realize that you’re constantly in a state of becoming’ says Dylan in Martin Scorsese’s 2005 documentary, No Direction Home. ‘As long as you can stay in that realm, you’ll sort of be all right.’

‘Key West’ is an example of the major theme of Rough and Rowdy Ways: Dylan’s own creative process. There’s even a song on here called ‘Mother of Muses’, Dylan begging the titular figure for a tune or two like Homer’s Odysseus. But the standout reflection on creation, one which brings death and life into steady collision, is ‘My Own Version of You’, a high camp number in which Dylan sings about sneaking around morgues to nick body parts. It’s gruesome, gothic, and silly – ‘I’ll take the Scarface Pacino and the Godfather Brando / Mix it up in a tank and get a robot commando’ – but it’s deadly serious, too, Dylan’s honest-to-God memoir about his deft ability to reanimate and refigure countless different influences to create something wholly new and original. And of course, Dylan’s singing about his finest creation, too, namely himself:

‘If I do it up right and put the head on straight

I’ll be saved by the creature that I create’

Then, later:

‘I can see the history of the whole human race

It’s all right there, it’s carved into your face’

These last two lines contain the two sub-topics implied in this preoccupation with writing and creation: the entire goddamn history of the world, on the one hand, and Bob Dylan, on the other. It was always thus, from Bob Dylan onwards, because the popular song is a repository of knowledge and wit and myth and wisdom, and Bob Dylan believes in the songs. On Rough and Rowdy Ways, Dylan, mad scientist, has given us ten more of his own necromantic songs—and I believe in them.

Join Revolution! May Day weekender in London

The world is changing fast. From tariffs and trade wars to the continuing genocide in Gaza to Starmer’s austerity 2.0.

Revolution! on Saturday 3 – Sunday 4 May brings together leading activists and authors to discuss the key questions of the moment and chart a strategy for the left.