Daniel Bensaïd’s memoir of a life as a socialist in France provides an engaging account of a revolutionary life during the 1960s and after, finds William Booth

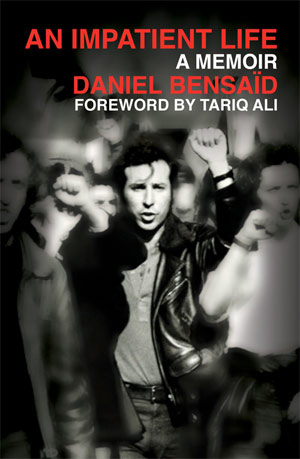

Daniel Bensaïd, An Impatient Life, trans. David Fernbach, forward by Tariq Ali (Verso 2013), xxvi, 358pp.

‘So many fallen, to whom we owe a debt’; so wrote Daniel Bensaïd (1946-2010), philosopher, writer and one of France’s leading revolutionary socialists for more than forty years (p.144). His death at the age of 63 was greeted with sadness and warmth from activists working in many left traditions, a testament to his heterodox ideology and collegiate approach. His memoir, published in French in 2004, has now been translated into English, providing us with a fascinating, dense account of many developments in global politics since the early 1960s.

Bensaïd’s writing style is both blessing and curse. For the more narrative sections of the book, it is a wonderful, lyrical prose which brings to life postwar France in vivid detail, but on occasions the political musings meander away from clear concepts with material roots and into something more florid and unreachable. The mood changes abruptly between chapters as incidents from different times in Bensaïd’s life are recalled; sometimes the effect is jarring, though often it is highly evocative.

The chapters on his youth are particularly engaging. He describes two momentous formative experiences which came to define much of his adult political life: the Algerian war of independence (and particularly the jingoistic reaction to the conflict of many of his French peers), and his expulsion from the French Communist Party. The latter led to the founding of the Jeunesse Communiste Révolutionnaire (Revolutionary Communist Youth) which grew out of the Left Opposition current within the Party and later evolved into the Ligue Communiste Révolutionnaire. At every mention of a political comrade, acquaintance, or enemy, a footnote gives a useful biographical note; the cumulative effect makes An Impatient Life into a fairly exhaustive Who’s Who of the postwar left, not only in France but across much of Europe and South America.

Bensaïd is keen to stress the organic or homegrown nature of his socialism throughout; the ‘vaccination’ he received as a young man against ‘certain mythologies’ was clearly of great importance to him. Instead, his political camp was decided ‘from the heart, initially’ (p.46). In intellectual terms, he drew on anthropology and psychology as much as political theory. This belief in having walked his own path manifests itself in a clear distancing from the ‘generation of 1968’, but Bensaïd nevertheless still sees the events of that year as a watershed, going as far as describing the previous two years as ‘prehistory’ (p.49). He himself was in the thick of the action, criticised by some for his willingness to form alliances with rival leftist groups in the attempt to form a broad revolutionary opposition to the university management and the police.

1968 and its aftermath

His remarks on 1968 are measured but tinged with bitterness. He remained furious with those who drifted towards the political centre (and in many cases, to the right) and concurrently depoliticised the legacy of the movement, downplaying its revolutionary content and repositioning it as an artistic or romantic venture.

‘The further the event retreats into the past, the more its worn-out actors lean with compassion and moist eyes over their departed youth, the more the fraternity of reactionaries raise their glasses, and the more the repentant wax ironic at their former naivety’ (p.266).

Yet by keeping 1968 rooted in the political realm, Bensaïd thinks it should also be placed in its proper historical context: ‘a modest fragment of the eternity’, just another step in the ongoing battle rather than a single fetishised moment (p.76). Nonetheless, the ‘contrast between the creativity of the street and the inertia of electoral representation’ made a deep impression; ‘all seemed to encourage the quest for a redemptive popular spontaneity’ (p.85).

Post-1968, there was the salutary experience of the 1969 presidential election and Alain Krivine’s paltry 1% of the vote (a ‘trap for fools’, p.95). Bensaïd also has a good deal to say on debates within Marxism. The Althusser-Lefebvre divide (perhaps known better in Britain in its Althusser vs. E.P. Thompson form) leads him to call for a place for ‘disorder and crisis’ rather than a neat, overly restrictive political framework (p.81).

The rise and fall of Maoist influence in France is covered in some detail, and again is a phenomenon whose scale and importance many British leftists may not have fully grasped. The more general crisis of the left in the 1970s is portrayed as a great rupture from which there has not (yet) been a recovery. In the 1980s (‘sordid’), Bensaïd returned to Marx’s work afresh, teaching – but also learning – the concepts and processes outlined in Capital particularly. This faith with Marx was forward-looking; following Derrida, Bensaïd was sure that ‘there will be no future without Marx. With him or against him, perhaps. But not without him’ (p.302).

Not everything was political (even though in some ways, of course, it was). Bensaïd describes his personal life candidly but with a light touch, allowing insight into his avoidance of military service as well as his sometimes clumsy efforts to break free from traditional romantic structures. Some of his remarks on women are crass to say the least, and in the sections on Latin America the creepy romanticised othering of women of colour is not – to this reader’s eyes at least – defensible. The woozy Brazilian and Mexican exoticisms frustrate all the more as they sit alongside some very useful political analysis of poorly-understood postwar lefts. The only other notable discomfort springs from his rather dismissive treatment of Ernest Mandel throughout.

South America, reform and revolution

Among the most captivating parts of the book is that on Bensaïd’s time in South America, meeting and debating revolutionary theory with militants in hiding from 1970s dictatorial regimes. While there is a useful broad overview of South American politics, Bensaïd also goes into some detail on the attractions and pitfalls of armed resistance as a political strategy. In directing the reader to other theoretical texts and memoirs, this book functions as a useful pointer as well as an important intervention in its own right. However, Bensaïd’s view has often been challenged; his assertion that ‘there could be an armed reformism’ and that there was no ‘unbridgeable border between reform and revolution’ belonged to a current of thought which still provokes a good deal of debate today (p.141).

On the narrower point of revolutionary violence, however, he held to Trotsky’s views which:

‘… imply in particular a categorical rejection of weapons of mass destruction that no longer make a distinction between civilians and combatants. They oppose wars of race or religion on principle. They condemn without appeal, for reasons that are both political and moral, attacks such as those of 11 September. Of course, no rule can respond to all concrete situations. But at least it makes it possible to designate and circumscribe the exception, instead of banalising it ‘(p.165).

Bensaïd is described in the cover notes by Tariq Ali as ‘France’s leading public intellectual’. This seems somewhat playful given the lengthy diversion on the role of the intellectual in political life in chapter two; Bensaïd delights in being called a ‘rustic philosopher’, an insult he was happy to wear as a badge of honour. He chooses not to define philosophy other than embracing its ‘lack of discipline’, it being ‘neither a vocation nor a priesthood’ (p.48). This broad, open stance is reflected in his description of the politics of his own political circle: an ‘oddly libertarian Leninism’ with ‘an egalitarian culture and a stubborn distrust of the effects of hierarchy and command’ (p.317).

Though this is a work of recollection, remembrance and reappraisal, it nevertheless engages with the current trajectories of capitalism and its associated political developments. Bensaïd anticipated the current debate on capitalism in the developing world, noting that ‘those who believed they were joining the First World by the royal road of the market found themselves cast into the Fourth World, with the horror of a mafia-style primitive accumulation of capital in the bargain’ (p.265). He also laments the loss of initiative suffered by the left, much of which became lost in a fog of ‘reformism without reforms’, opposed by ‘conservative neoliberals now claiming the banner of dynamism and movement’ (p.204).

While hopefully things have changed in the decade since he made that observation, a broader warning remains relevant; that ‘the unambiguous determination of the ruling class and its arrogant simplifications … tends, by a perverse mirror effect, to find its reflection in the rhetoric of the oppressed’ (p.212). In other words, we should interrogate the present in its own terms, using the tools available to us, and reject the narrow frameworks of debate thrust upon us by the ruling class.