F Scott Fitzgerald’s novel about class and wealth in 1920s USA is a brilliant piece of writing and remains as relevant as ever in our times, argues Lindsey German

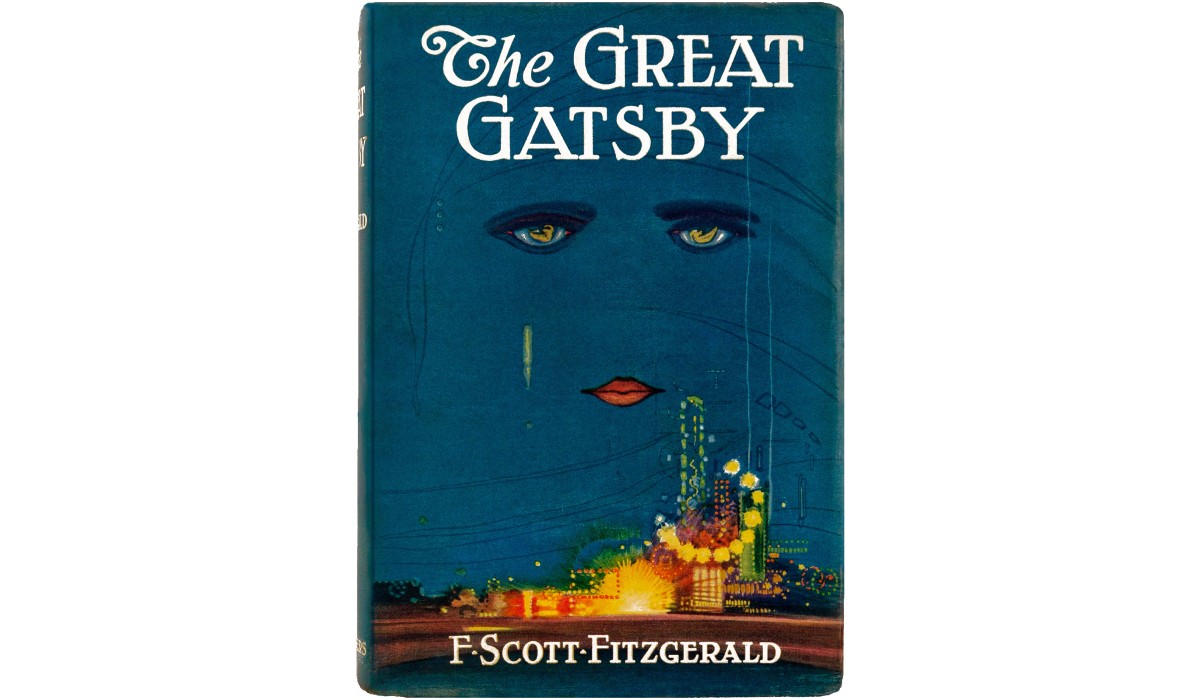

It’s often called ‘the great American novel’ or a ‘story of the American Dream’. F Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, published 100 years ago this month, is the tale of a mysterious man from a poor background who reinvents himself through phenomenal wealth, but whose achievement is neither happy nor enduring, and whose unrequited love turns to ashes amid tragedy and despair. But this is not a morality tale about him, who remains a sympathetic if flawed character throughout the book.

The remarkable thing about Fitzgerald is that he manages to depict the world of Jay Gatsby – his huge Long Island palace based on the design of a town hall in Normandy, his glamorous Jazz Age parties, the sumptuous food and cocktails – not as something desirable and worth emulation but as the symptoms of a system absolutely rotten to the core.

The story is narrated by Nick Carraway, like Fitzgerald, a Midwesterner from a fairly wealthy background, whose rented house is next to Gatsby’s mansion, and who therefore has a close-up view of the man, the myths around him, and the actions that lead to his downfall. He is also a distant cousin of Gatsby’s love, Daisy, now married to Tom Buchanan, and living just across the bay in their own massive pile.

The descriptions in the book are often magical: ‘In his blue gardens men and girls came and went like moths among the whisperings and the champagne and the stars’.

But Fitzgerald never forgets who makes this happen: ‘And on Mondays eight servants, including an extra gardener, toiled all day with mops and scrubbing-brushes and hammers and garden-shears, repairing the ravages of the night before.’

Fitzgerald wrote the book as a young man in his twenties, already a successful author at 23, when he and his wife Zelda were already part of this world. Their own story is one of rapid fame and wealth, a few years of glittering parties and international travel which ended with Zelda’s serious mental illness while Fitzgerald continued his heavy drinking.

Careless wealth

His perspicacity and acuteness about this world stands out. It is a world he already despises. Tom Buchanan is possibly the worst character in the book. Fitzgerald gives him two specific instances of white supremacist, racist remarks. Early on, we learn that he has ‘women’ other than Daisy, and in a drunken scene with his mistress, Myrtle, he breaks her nose when she talks about his wife. Daisy herself is in a different way the victim of the extreme sexism inherent in the system. She tells Nick what she said on the birth of her daughter: ‘I’m glad it’s a girl. And I hope she’ll be a fool – that’s the best thing a girl can be in this world, a beautiful little fool’.

Daisy isn’t a fool however – wealth and status override her love for Gatsby, and her voice is described as sounding like money. Tom is extremely rich, callous and selfish. Fitzgerald writes of him and Daisy: ‘They were careless people, Tom and Daisy – they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made …’ Those subject to the attentions of these careless people – Tom’s mistress Myrtle and Daisy’s lover Gatsby – face a double tragedy.

Jay Gatsby tells different stories about how he got his wealth. In reality, he was a soldier in the First World War, who got promoted and when he returned to the US made a fortune from bootlegging and organised crime. His love for Daisy prompts him to create his huge estate, organise glittering gatherings of the rich and famous – who show absolutely no interest in him as a person – and hope desperately that this will impress her and rekindle their love.

Gatsby learns the hard way that ‘new’ and ‘illicit’ money doesn’t trump old money and that the brutality of the US ruling class is expressed through a system which screws (often literally) working-class people, treats obscene wealth as its birthright, and abandons supposed friendship and love in the face of difficulty. The party goers abandon Gatsby when scandal hits and his funeral is attended by his poor farmer father (real name Gatz), Carraway and the servants.

Fitzgerald’s life became more erratic with heavy drinking, debt and Zelda’s illness. He wrote little of length until the 1930s when he produced Tender is the Night, which is a darker novel in many ways. He ended as a Hollywood scriptwriter, writing for films such as Three Comrades, and died young. His last novel is the unfinished The Last Tycoon, about a movie mogul.

The Great Gatsby has been made into several film versions, none of which I quite feel do it justice. It deserves to be read: it is near perfect observation of a particular time, when triumphant US capitalism (and imperialism) ran wild, its robber barons mirrored by the gangsters their system also created. And, at a very short 55,000 words, it is an incredible achievement of character and plot. At 100 years old it remains a very modern novel.

Join Revolution! May Day weekender in London

The world is changing fast. From tariffs and trade wars to the continuing genocide in Gaza to Starmer’s austerity 2.0.

Revolution! on Saturday 3 – Sunday 4 May brings together leading activists and authors to discuss the key questions of the moment and chart a strategy for the left.