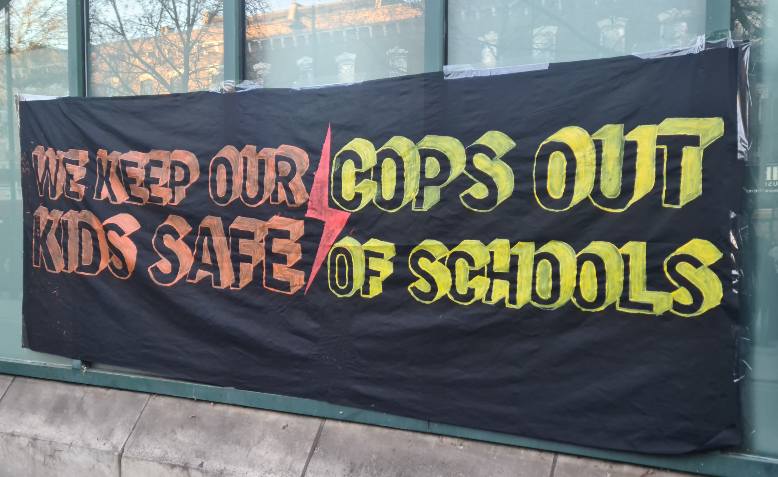

Justice for Child Q protest. Photo: Elly Badcock

Justice for Child Q protest. Photo: Elly Badcock

The shocking story of Child Q is not isolated, it is symptomatic of a racist system that needs to be dismantled, writes Alia Butt

For the purpose of this article, I will be using the unsatisfactory term BAME used to signify Black, Asian, and Minority Ethnic people.

I work in London as a psychotherapist in the NHS. Recently, the story of Child Q – a 15 year old Black girl who was strip searched by two officers without any other adult present and without her family’s consent – has become common knowledge. But the unsettling truth is that her horrendous experience of racist and misogynistic targeting; of abuse and adultification; of humiliation and terrorisation, is not an isolated one.

What Child Q has forced us to remember is that the bodies of people of colour are not only insignificant but are a battle ground. Despite the progress we have seen, the ideological differences imposed on BAME bodies continues to exist.

The reality is that institutional racism is still rife. For example Black Londoners are three times more likely to be strip searched. Statistics provided by the Metropolitan police show that thousands of children have been strip searched in the past five years – a quarter of whom are younger than 16, with 35 under the age of 12 – and in 2020, 26 children were strip searched and 60% of them were Black.

The information around the abuse this young person was subjected to has taken two years to reach the mainstream. In that time, countless young Black girls have been mistreated and many of their voices have gone unheard. Sadly, many will remain that way. These abusive and unsafe systems include the schools that these girls are forced to attend, where they are continuously treated like criminals for crimes such as wearing their hair in traditional styles that offend their mostly white teaching staff.

In my daily work I often hear about the impact that racism has on our young people – particularly Black and Muslim children. Young people of colour are continually dehumanised by the system. They are criminalised before any reasonable doubt has even been provided, they are humiliated in front of their peers and punished if not entirely dismissed by the systems in place to protect them.

Some young people I work with talk about finding it hard to speak about racist treatment to white therapists. Young women talk about their bodies not fitting a Eurocentric ideal of beauty and a desire to ‘fix’ it. Many young people are not only fearful of the way they are treated but also internalise ideas around being ugly, lazy, difficult, aggressive, but crucially that they are worth less.

Many speak about the impact of feeling targeted by their teachers as well as by the police. Young men are struggling to leave their homes because they feel they are being watched or that their skin is something to fear and detest, but they also speak about the very tangible fear of being stopped and brutalised by police. Now we are hearing about how these officers have found their way from the street and into the classroom, leaving our BAME children absolutely nowhere left to feel safe except the confines of their bedrooms.

The problem of racism is endemic

Our politicians struggle to provide any sensible solutions. The Prime Minister’s delay in commenting on the mistreatment of Child Q spoke volumes, but other members of parliament also fail to see the insidious problems around systemic inequality and abuse. Sadiq Khan’s call for more police officers in school is tone deaf and dangerous for young Black and Muslim children who are criminalised due to the xenophobic structures that allegedly overwhelms academy schools in London.

I myself was remined of my own sixth form days (that were entirely coloured by the racist aftermath of 9/11) by Angela Rayner’s comments suggesting we should ‘shoot first and ask questions later’, a policy that would inevitably lead to more BAME deaths than white. BAME people remember what happened to Jean Charles de Menezes, Mark Duggan and many others, and know too well that such a policy is simply a license for greater police violence against minorities.

The staggering difference in the treatment of BAME people and their white counterparts by official institutions and policy is neatly summarised in the government’s latest plan to “offshore” refugees. While our government has shown practical and moral support for Ukrainian refugees, though far from enough, it’s expanding hostile environment for other refugees is a reminder of the insignificance of thousands of BAME lives still being quietly sacrificed all over the world (e.g. Afghanistan, Sudan, Somalia, Palestine, Syria; the list goes on), and the millions of BAME refugees that are left to die while desperately attempting to seek refuge in Europe. How wonderful would it be if the UK government were prepared to provide a monthly £350 to Britons who house who refugees of all races, not just white ones.

Truth is revealed in times of crisis

Racism is deeply rooted and extends further than we may acknowledge. Harmful and racist narratives around health have for centuries insisted that BAME individuals are more susceptible to disease, or more likely to struggle with their mental health due to organic causes. Due to the Covid-19 pandemic, society has moved in fast forward; we have seen huge changes in global socio-economic relations. This has brought to light the biased structures in society that impact health.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the Conservatives shamefully attempted to explain the disproportionate impact of the virus on BAME people as a biological phenomenon. Studies over the pandemic show BAME people suffer significant social disadvantages – poorer living conditions, language barriers as well institutional racism (gate keeping of health services, higher education, positions of power/influence and higher wages) – which largely impact mental and physical health.

There have been several reports into institutional racism, yet we have not seen the recommendations being acted upon. When you look closely at the levelling up scheme introduced by the government claiming to address structural inequality, it is clear it is being used to perpetuate and further deepen inequality. Last year’s Tony Sewell-led government report outrageously found that institutional racism no longer exists. This state level denial and propaganda only further implies that racism is engrained in the system and what we continue to see is that the police, as defenders of the system and not the people, reflect and perpetuate that racism.

In the wake of Child Q’s story reaching the eyes of the community, the outrage was palpable. Many children walked out of their schools and colleges and protests erupted around the city. As I sat outside Hackney Town Hall listening to the powerful speeches demanding justice for Child Q, I noticed the overwhelming message appeared to be one of a plea similar to my own. We must not allow the anger and appetite for change ignited by the painful reality of Child Q and others like her to fizzle out and fade away. We must continue building the movement against racism as widely as we can. Clearly this racist and sexist system has no intention of changing from the top, so we the people, must force it from below.

Fund the fightback

We urgently need stronger socialist organisation to push for the widest possible resistance and put the case for change. Please donate generously to this year’s Counterfire appeal and help us meet our £25,000 target as fast as possible.