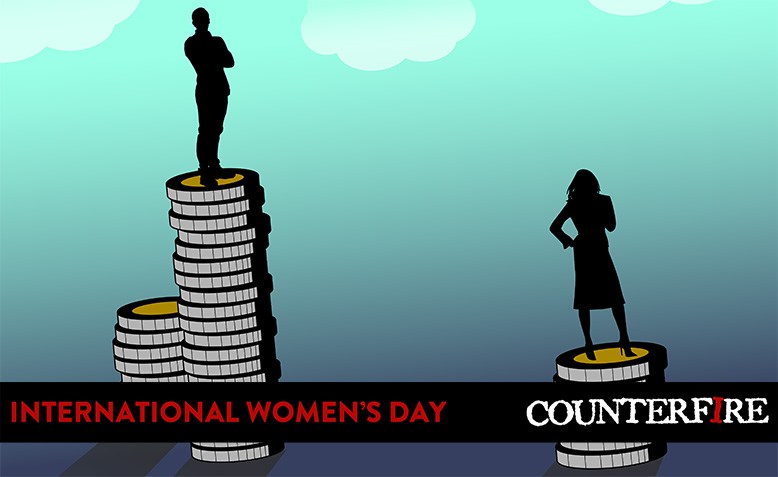

Gender pay gap illustration. Photo: Public Domain

Gender pay gap illustration. Photo: Public Domain

On International Women’s Day, Terina Hine looks at why the gender pay gap is still as wide as it was 25 years ago

The gender pay gap persists, despite various policy measures introduced over the last few years. And it’s not just the pay gap that sustains workplace inequality; women continue to face unequal pay, unequal conditions and greater challenges to their work-life balance than their male counterparts.

Although there have been modest improvements to overall earnings in the last 25 years, these have been mainly explained by women’s greater education attainment. The contribution of government policies to closing the pay gap has, according to the Institute of Fiscal Studies (IFS), been close to zero.

Inequalities in earnings, working hours and hourly wages are significant. It is 52 years since the Equal Pay Act was made law, and in 2017 companies were forced to publish gender pay disparities, but still by 2019 women on average earned 40% less a week, £3.10 less an hour, than men.

The gender pay gap is not the same as equal pay – when women are paid less than men for doing the exact same work. The gender pay gap describes the average difference between hourly wages for men and women and is calculated using either the mean or median average. According to the Fawcett Society most companies report the median figure, perhaps because this can least easily be skewed by a small number of high earning female employees.

Nevertheless, the latest figures reveal that more than three in four UK companies pay male staff more than female staff.

Research by the IFS reveals this discrepancy is greater for higher income earners (the highest female earners take home 67p compared to £1 for the best paid men). Inequality in average pay is greatest among graduates, with male graduates earning 23% more than female graduates.

But these figures show hourly wage disparity and hide greater inequality. As in other areas of life, the poorest and least educated women suffer the most: taking overall earnings, the gap is largest when comparing men and women with the least qualifications. Why? Because less educated women in lower skilled jobs work fewer hours than their male counterparts, and are more likely to not work at all.

Existing policies, including parental leave, childcare and the tax and benefit system sustain and incentivise a traditionally gendered division of labour, even when supposedly gender neutral. For example, welfare subsidies that are taxed away with increased family income is a disincentive to second earners - usually women.

On average women work eight fewer hours a week than men, there are 10% fewer women in the workplace than there are men and they get paid an average of 10% less, while women do almost two hours a week more unpaid work. In addition women have less autonomy in the workplace, a greater burden for care, and on average have poorer working conditions (both physical and emotional) compared to male colleagues.

And then there’s the motherhood gap – not only does a career break harm one’s career, but once a woman returns to the labour market she is more likely to opt to work part-time, choose work closer to home, often to the detriment of salary or career, or take a position with more flexible hours to prioritise the needs of her family.

Women are also accused of failing to put themselves forward for promotion or a pay rise, apparently they are not helping themselves. There may be some truth in this, but being more assertive will do nothing to challenge the institutional structures stacked against women, and such a focus certainly has a whiff of victim blaming.

It is the responsibility of employers to counter workplace impediments to equality, and government to put in place policy that enables a more equal pay distribution and division of unpaid labour. After all, six in ten women say it is the demands of caring responsibilities that prevent them from applying for new jobs and promotion, not fear of failure or inbred timidity. And according to a recent Ipsos Mori poll, one in five women left a job because of the difficulties of balancing work and care.

The position for black, Asian and mixed race women is worse still, with more ethnic minority women taking on adult caring responsibilities than their white sisters. This research, conducted by Ipsos Mori and the charity Business in the Community, found that while just over a third of the labour force has unpaid caring responsibilities, women account for 85% of sole carers for children and 65% of sole carers for adults; these figures were even higher among ethnic groups.

And the pay gap does not end when women stop getting paid; in fact the pension gap is even bigger. Women are unable pay into their pensions when they are off work caring for children, and a lower income overall compounds over time into a considerably smaller pension pot.

Gender-based inequalities in the three main areas of the labour market remain large: in employment opportunities, in working hours and in hourly wages, and all increase significantly after having children. The overall inequality in both society and in work urgently needs to be addressed.

What’s clear from the data is that the inequality faced by women is deeply rooted in the class structure of our society. It will take collective action and solidarity to go beyond the individual liberal solutions (that clearly don’t work) and instead confront the inherently exploitative system to win equality.

Join Revolution! May Day weekender in London

The world is changing fast. From tariffs and trade wars to the continuing genocide in Gaza to Starmer’s austerity 2.0.

Revolution! on Saturday 3 – Sunday 4 May brings together leading activists and authors to discuss the key questions of the moment and chart a strategy for the left.