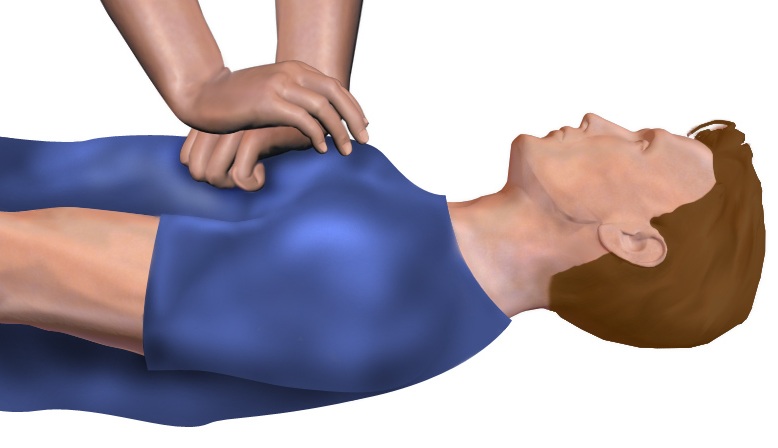

Adults CPR. Source: Wiki commons

Adults CPR. Source: Wiki commons

The resurgence of DNACPR should be challenged, the idea that one life is more worthy than another could lead to dangerous consequences, argues Elly Badcock

Autistic people and people with learning disabilities were told they should not be resuscitated if they become severely ill with coronavirus, the BBC reported today. Andrew Cannon, CEO of the care company running the homes said there was ‘No consultation with families, no best interests [committee]. Mostly working-age adults. We will fight this.’ It is rare to find an article on this website that opens with an endorsement of anything uttered by a CEO, much less a CEO profiting from the care that should be funded and provided by the government; but these are unprecedented times.

This is not the first time that DNACPRs (Do Not Attempt CPR) have been discussed in the media recently; a Welsh GP surgery also contacted people with heart and lung conditions encouraging them to sign similar notices. The discussion in the healthcare system and media around this kind of involuntary euthanasia, particularly people with learning disabilities who may be less able to understand the concept of death and dying, or advocate for their own needs, should be ringing extremely worrying alarm bells. As Steve Silberman so harrowingly outlines in Neurotribes, his social history of autism, the Nazi extermination program against disabled people (called the T4 program) is now widely considered a dry run for the Holocaust. The Nazis were able to carry out the T4 program so effectively precisely because they had whipped up the sentiment that disabled people’s lives were worthless, as they were less likely to contribute to the economy. At state-run ‘clinics’ in Vienna, thousands of disabled children and adults were murdered by the state. The cause of death listed in letters sent to the families was often pneumonia – a handy catch-all for obscuring the fact that victims had starved or frozen to death.

Silberman had initially been puzzled at the lack of uproar from these families. Letters back to the clinic in response to their child’s death were pleasant and restrained. But these were families who had been told over and over that a person’s worth depended on what they were able to contribute. That their beautiful children were a burden on society that should be hidden away; that they were disfigured and deformed. It is less of a surprise that families beaten down by relentless and open disgust for their children might react in this way, although it doesn’t make it easier to stomach.

We might think we have come a long way since then. In some ways, we have; and comparisons to Nazis rarely make for effective political argument. But the parallels are deep and disturbing. In the most recent election, Conservative candidate Sally-Ann Hart argued for removing the minimum wage for people with learning disabilities, implying they should be grateful for “The opportunity to work because it’s to do with the happiness they have about working … Some people with learning difficulties, they don’t understand about money.” The Independent Living Fund, which enabled people with learning (and other) disabilities to live in the community instead of in residential homes, has been shut down as a result of austerity. The shambles of a benefits system that exists has declared people fit to work when they aren’t, leading to avoidable deaths and suicide. People with learning disabilities and their families are treated as ‘folk devils’ in the media, an unending drain on resources that could be better put to use elsewhere.

It is in this storm of hatred that we see harrowing stories of people with learning disabilities being placed on DNACPR orders without their consent. Anne Clifford died after being admitted to the hospital with breathing difficulties, where the staff did not properly feed her for a week. Anne’s sister told Mencap: “A DNACPR (Do Not Attempt CPR) notice was put on her file – without even discussing it with me first. They claimed she was brain damaged, but everything they described were things she did all the time.” The 2019 Learning Disability Mortality Review reported that 19 people with learning disabilities who died, had ‘learning disability’ or ‘Down’s Syndrome’ listed as the sole reason on their DNACPR notices. These seem like singularly heartless decisions – but they are the result of a society that ranks peoples’ worth by their productivity.

In essence, clinical discussions do not and have never existed in a social vacuum. Healthcare professionals are part of a society that is constantly fed the narrative that people with learning disabilities are financial drains, bed-blockers, and unable to contribute. Healthcare professionals make subconscious (and occasionally very conscious) decisions about what kind of life is worth living based on this insidious drip-feed of negative ideology. In a society set up to prioritise production and profit, rather than human need and happiness, it is hard to find a place for people who cannot work, who may not understand the concept of work. But what about the desire to stay alive to participate in everyday life? To forge connections with friends and family? To enjoy the world around them? Are we ready to live in a society that deems these activities worthless, because they’re not turning the cogs of capitalism?

Clinical discussions of course have their place. Ventilation requires days of lying face down, with invasive breathing and feeding equipment in place. It takes an enormous toll on the human body, with extensive rehabilitation required afterwards. Many people will take the decision that they don’t wish to put their body through this, much like many cancer patients decide not to pursue chemotherapy. Of course, this choice should be respected; but crucially, it must be the choice of the person undergoing the treatment.

These should be discussions that happen in advance of the patient becoming ill. But many clients with learning disabilities don’t have advanced care plans in place that outline what they want to happen at the end of their life, although Mencap and other organisations do excellent work to promote this planning. Years of austerity has meant that NHS clinicians are not able to devote the time needed to such an important and sensitive task.

This is an endlessly complex, difficult and challenging discussion. The roots of hatred against people with learning disabilities are heartbreakingly deep, and the Covid-19 crisis has only uncovered a small portion of this. But there are things we can do in the here and now to challenge this rhetoric and assert that everyone’s life is worth fighting for.

Firstly, a strong demand for more ventilators. The government have acted shamefully in putting the interests of profit above public health. Anyone able to produce ventilators must now do so, including arms manufacturers, car and plane producers.

Secondly, deaths that occur in care homes and supported living must immediately be included in the national death toll figures. The news that 15 people in one care home died from Covid-19 is horrific but not unexpected; understaffed and underfunded care homes mean that staff lack the PPE and training to perform basic infection control, and the government must not be allowed to sweep this monstrous failure under the carpet.

Finally, proper testing and contact tracing must be introduced. It is shameful that NHS and private social care staff are going into work not knowing if they are infecting their patients. Because people with learning disabilities are often less able to tolerate the invasive swabs for Covid-19, it is essential that they are working with staff who they know will not infect them.

Every one of us has a responsibility to challenge the idea that one life is more worthy than another; to save lives in the here and now, but also to ensure that we can look forward to a future where the full spectrum of human experience is not just tolerated but cherished.