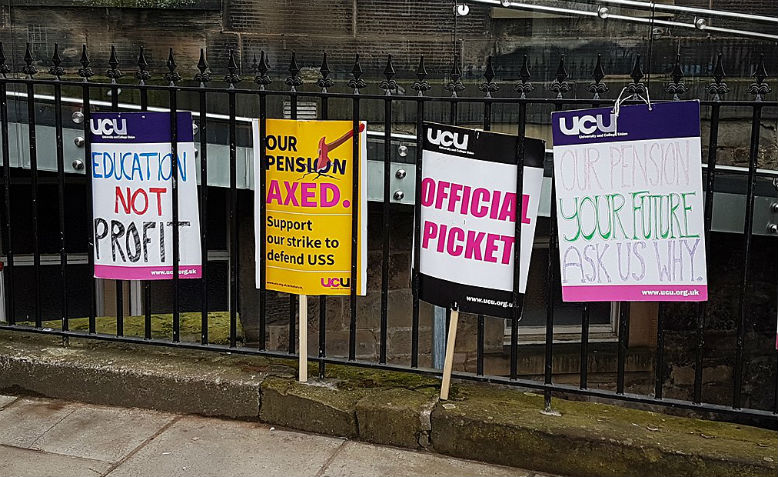

UCU placards during the 2018 higher education strike. Photo: Stinglehammer

UCU placards during the 2018 higher education strike. Photo: Stinglehammer

Industrial action is the only way to improve conditions in higher education

Universities are the latest sector to ballot for industrial action following Royal Mail workers in the CWU and civil servants in the PCS.

Union members in universities across the UK are being balloted on pay inequality and associated issues of casualization and excessive workload. At the same time, UCU members in pre-1992 universities who are part of the USS pension scheme are being balloted over the unresolved pension dispute. Both could lead to strike action.

In Higher Education, UCU figures show that women are paid on average 15% less than men while disabled workers earn on average 9% less than their colleagues. Black academic staff earn 12% less than their white colleagues. There are over 100,000 staff employed throughout the sector on fixed term contracts affecting their ability to rent or get a mortgage as well as suffering the stress levels associated with it. A further 70,000 are on other types of casual contracts making HE one of the most casualised sectors in the UK. Meanwhile, a typical working week for academic staff is estimated at 50 hours. Pressures from teaching and research targets plus administrative burdens have increased as jobs are lost. And on top of all this our salaries have fallen by over 20% since 2009.

This is a sector in crisis – for staff far more than for employers. House of Commons Library figures show that the sector has had surpluses every year bar one since the early 1990s. Surpluses for the last two years have been over £1 billion and while they are set to fall in 18-19, official figures show they are likely to increase again after that.

Thanks to tuition fees, revenue has increased by nearly 400% since 1994 from £10 billion to over £38 billion a year. There are an estimated £44 billion held in university reserves. Where has this additional cash gone? Certainly not into pay packets given the fact that staff costs have decreased in that period from 58% to 54% of expenditure.

On top of falling pay and rising workloads, research active staff are faced with constant pressure to bring in grant funding. In 2016, Newcastle University UCU had a major victory against what was called “raising the bar” where staff performance was to be measured against funding success and where failure to bring in adequate amounts could lead to dismissal. The scheme would have seen “research and performance expectations” leading via a traffic light system to staff being placed on the capability procedure for “failing” to bring sufficient grant funding in or to publish enough papers. Industrial action in the form of a marking boycott and the adoption by UCU of the dispute as one of ‘national significance’ was enough to force management to withdraw the plans. This is the spirit we now need to win back control of our working conditions and to improve students’ learning conditions.

As if this wasn’t enough, for staff in the pre-1992 universities, our pensions continue to be under attack. The dispute we had last year with the employers was the most sustained strike action ever seen in the sector. It ended with an uneasy compromise of a Joint Expert Panel (JEP) being set up to look at the reasons for the dispute: effectively a valuation which was largely regarded as suspect. JEP came back in September 2018 with proposals which would have meant only a slight increase in payments for both staff and employers. The JEP proposals were then torpedoed by the USS Board, chief executive Bill Galvin and the government appointed Pensions Regulator. Following this, the employers fell into line, contributions are set to increase and we are back in dispute.

It is worth noting who these individuals are. Galvin has been Group Chief Executive Officer of USS since August 2013 and has overseen a series of attacks on our pension scheme. Prior to this he was CEO at The Pensions Regulator for three years and before that its executive director for strategy. The rest of the USS group executive are mainly former employees of JP Morgan, Merrill Lynch. Morgan Stanley and even the bankrupt bank Lehman Brothers. Of the 12 trustees who oversee the scheme on behalf of the members, four are from the employers, three from UCU and five independents. The five supposedly independent trustees all have the same background in high level jobs in huge financial institutions. As for UCU’s small representation, the one trustee, Professor Jane Hutton, who challenged USS behaviour has been suspended.

The Pensions Regulator itself is supposedly an independent watchdog for the pensions industry but is in fact a government appointee driving the shift of pension schemes from defined benefit (DB) schemes to much more volatile defined contributions (DC) schemes. This is what is at the heart of our dispute. Current proposals accepted by the employers are moving the scheme to more unaffordable and less desirable places and it is likely USS will come back in the near future with another set of proposals again attempting to move us to DC. DB means a guaranteed income when you retire while DC means you don’t know what you are going to get at any point in time. It individualises the risk whereas, at the moment, that risk is shared across all members and institutions.

We need to get 50% of members voting per institution, a stipulation of Tory anti-union laws. As unfair as this is, it forces us to start campaigning in a serious fashion to get the vote out. We have recently returned large ‘yes’ votes for action over pay and casualisation but, having failed to meet the 50% threshold, the result was declared null and void.

This time we have a new general secretary, Jo Grady, an activist from the rank and file. She is touring the country to encourage ‘yes’ votes and the atmosphere around her appointment is one of excitement. But what we do on the ground among the rank and file is the key to launching another dispute which this time must end in a clear and resounding victory for the union.

This will require comprehensive and energetic campaigns “to get the vote out” and to reassure members that industrial action is the only effective means of safeguarding conditions in higher education. It also means connecting to other campaigns as a means of making our branches – and our campuses – hotspots of mobilisation and activity. We should, for example, be joining with students in the climate strike movement (and demanding that our managements fully support action). We should join with students and call for the scrapping of tuition fees as well as the universities using some of the billions they have in reserve to pay back students who have built up huge debts over the past 20 years. We have to aim for an autumn of discontent.