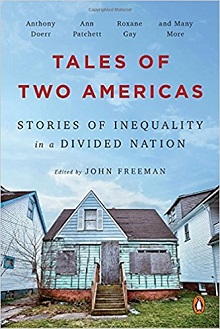

A new collection of writing about poverty in the US shows that America is broken, but the answer is to join in the struggles on the streets, argues Elaine Graham-Leigh.

The starting point for this collection of essays and short stories is that America is broken. ‘You don’t need a fistful of statistics to know this’, John Freeman argues in his introduction.

‘You just need eyes and ears and stories. Walk around any American city and evidence of the shattered compact with citizens will present itself. There you will see broken roads, over-loaded schools, police forces on edge, clusters and sometimes whole tent cities of homeless people camped in eyeshot of shopping districts that are beginning to resemble ramparts of wealth rather than stores for all’ (p.x).

The tales here bear witness to the realities of living in such a profoundly unequal society. They move from personal stories of hardship, like the unemployed graduate reduced to selling his blood for food money, or a couple scraping by on mowing the lawns of the houses repossessed when the banks foreclosed, to accounts which indicate a bigger picture.

This is particularly the case for various stories dealing with housing, homelessness and gentrification, which combine to drive home the message that for people in poor neighbourhoods, so-called urban renewal is always ‘someone else’s renewal, not our own’ (p.22). In Seattle, as in ‘all the other gilded brain capitals prospering in their lovely settings’, the well-paid longshoremen jobs, which used to give them ‘equal footing with citizens labouring in offices overlooking the sound’ are long gone, and ‘a leaky shack in the Bay Area’ comes with a $1m price tag (p.147).

Although Seattle’s radical tradition is not entirely forgotten, as the title of Timothy Egan’s essay has it, ‘we share the rain and not much else’ (p.146). In Portland, meanwhile, as wages have stagnated or declined since 2000 and house prices have risen by 14% a year, the homelessness crisis has seen tent cities reminiscent of the 1930s return to the streets. As Karen Russell points out in her essay on Portland, the poorest third of Americans have seen their housing costs increase by half since 1996, meaning that they are extremely vulnerable to homelessness. ‘If you are spending half your income on housing, the spectre of eviction is always near’ (p.237).

Gentrification is most obviously and most immediately about housing, but as Rebecca Solnit’s essay ‘Death by Gentrification’ describes, it can also have far-reaching effects on the nature of communities. As cities like Seattle or San Francisco become the preserve of highly-paid (mostly white) tech workers, the original inhabitants (particularly if they are Black or Hispanic) can be treated as interlopers in what should be, but increasingly is not, their own space. For Alex Nieto, shot dead by San Francisco police after he was reported to them for suspicious behaviour (sitting on a park bench), the effect of gentrification was that ‘a series of white men saw him as a menacing intruder in the place he had spent his whole life’ (p.2).Nieto’s story is an especially shocking demonstration of how poor, black lives do not matter, either to the police or to the white people who move into ‘edgy’ neighbourhoods and then fantasise about being able to shoot the working-class residents they find threatening.

Solnit’s essay shows how an analysis of one incident can shed light on a process happening in every prosperous city in America; it encapsulates how individual stories can be powerful. It is, however, the standout story in a collection which does not always manage to bring out the wider meaning behind the tales it contains. It is not usually good reviewing practice to criticise the work under review for not being something else, but there are issues here which may be inherent to the nature of the project.

While the pieces here range from factual journalism to fiction and poetry, many are autobiographical; writers reflecting on their own experiences of class and inequality. For writers from poor backgrounds, being expected,as a result, to write about poverty can clearly be dispiriting. Chris Offutt, ‘a country boy who’s clawed his way out of the hills, one of the steepest social climbs in America’, discusses his discomfort about being asked to ‘explore “trash food” because…“you write about class”’ (p.71). It is a good point, but it does rather raise the question of how he felt about being asked to write about that experience for this volume, again because of his background.

Offutt’s piece also reveals a distancing issue which arises from asking ‘major contemporary writers’ to write about their personal experiences of poverty and exclusion. That is, having made it as ‘major contemporary writers’, they may be poor (writing not being a well-remunerated activity) but they are unlikely any longer to be part of the disregarded and despised underclass whose stories they are telling. Some, like Offutt, are writing about the childhood poverty they have now escaped; others recount poverty they witnessed but did not experience, as with Brad Watson’s memories of his parents’ maids, or Karen Russell’s account of other people’s homelessness in Portland.

This is not, of course, to argue that only stories arising from current, personal experience would be valid. By its very nature, this is an issue which most writing on poverty has to face, and there are different ways of dealing with the inevitable separation of someone who has the wherewithal to publish their words, from the unheard about whom they are writing. Some of the best confront the issue head on, as for example Matthew Desmond in Evicted, on his feelings of guilt about living as a fieldworker in a trailer park in Milwaukee:

‘I felt like a phoney and a traitor…I couldn’t help but translate a bottle of wine placed in front of me at a university function or my monthly daycare bill into rent payments or bail money back in Milwaukee. It leaves an impression, this kind of work. Now imagine it’s your life.’[1]

Barbara Ehrenreich nails it in Nickle and Dimed, her account of trying to get by on low-wage work, where she reflects that the world she is visiting for research is one where, but for historical accident, she might have lived:

‘Take away the career and the higher education, and maybe what you’re left with is this original Barb, the one who might have ended up working at Wal-Mart for real if her father hadn’t managed to climb out of the mines.’[2]

The difficulty with this collection is that, in comparison, lacking such considerations, the cumulative effect is that, unintentionally, we are looking at divided America from the more prosperous side of the divide.

The focus on personal experience also tends to stress personal, individual responses to poverty rather than collective resistance. Karen Russell, for example, is explicit that understanding the structural issues behind the homelessness crisis in Portland will ‘depress and overwhelm you to such a degree that you opt out of caring altogether.’ What matters is the ‘individual, eye-level efforts to reach one another: the homespun web of neighborshelping neighbors.’ (pp.238-9) Other pieces, such as Eula Biss on white debt, or Joyce Carol Oates on a white woman looking for a way to help the Black Lives Matter campaign, seem to conclude that there is very little we can do, even on an individual level. This is despite the fact that, as evidenced by Rebecca Solnit on San Francisco, there are hard-fought campaigns all over the US against evictions, gentrification and, of course, police violence. The book, according to the back cover, demonstrates ‘how boundaries break down when stories are shared’. More space for the many examples of collective struggle breaking down those boundaries in action might have lifted this collection from the rather hopeless impression given by many of the pieces here.

Faced with the immense structural problems of a system run for the benefit of the 0.1% at the expense of everyone else, the way out of the ‘cul-de-sac of guilt’ (p.238) is organising together. As Pete Seeger said in 1963 about the civil-rights struggle;

‘If you would like to get out of a pessimistic mood yourself, I’ve got one sure remedy for you. Go help those people down in Birmingham or Mississippi or Alabama.’[3]

The evidence of this collection is that America is indeed broken, and has been broken for a very long time. It is necessary to tell the stories which bear witness to the damage that poverty and inequality are doing, but it is equally important to build the fightback. The silver lining to the disaster of Trump’s election has been that for every liberal wringing their hands at the result, someone else has been inspired to get out on the streets. If Trump does come to the UK in 2018, we must show our solidarity with all the downtrodden whose stories are told here, by doing the same.

Tales of Two Americas. Stories of Inequality in a Divided Nation is available exclusively from O/R Books.