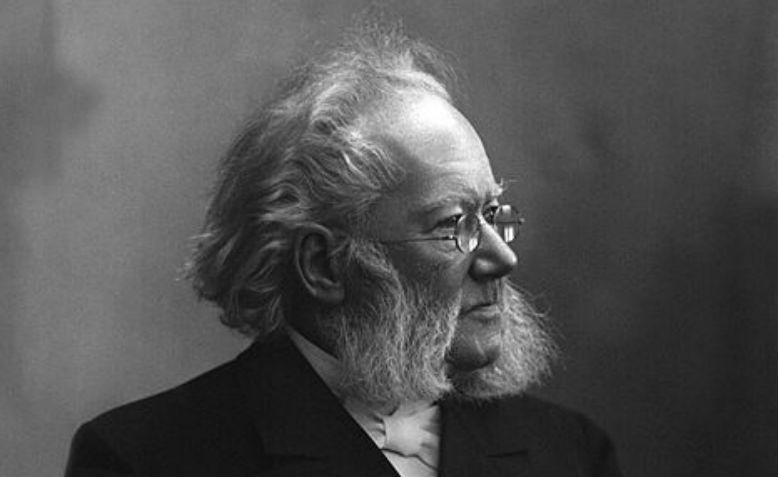

Henrik Ibsen. Photo: Wikipedia

Henrik Ibsen. Photo: Wikipedia

Ibsen’s play isn’t feminist, but the role is still one of the theatre’s most exciting female characters – brutal, mad and vengeful

Hedda Gabler, the central character in Henrik Johan Ibsen’s 1891 chamber piece, which is currently playing at the National Theatre, is a woman out of time and out of place. She’s an independent woman trapped in a 19th-century bourgeoisie marriage. She is also a powerful female lead, stuck in a play written by a man with deeply conflicted attitudes to women. Hedda is the embodiment of Ibsen’s contradictions. Ibsen wrote, ‘Men and women don’t belong in the same century. [Women] realise life holds a purpose for them, but they cannot find that purpose.’ It is an attitude that is both sympathetic and scornful, the views of a man, himself out of time, sensitive to the plight of women but quick to lay the fault at the feet of women themselves.

That said, he is clearly fond of Hedda: she’s manipulative, cruel, even evil, but Ibsen allows us to revel in her wickedness. Her responses to the world around her are extreme, and much of her predicament is self-inflicted, but the world around her is full of obstacles and barriers which she is butting up against hard. She is a woman drowning and as she does, dragging those around her down with her, intent on not being the only one to suffer. But the play is also about something more universal, a quest for purpose, for meaning. Ibsen also wrote, ‘The great tragedy of life is that so many people have nothing to do but yearn for happiness without ever being able to find it.’

If Ibsen is the ‘father of realism’, Belgian director Ivo van Hove’s production brings out the surrealist in him too, and the play is at its best when it takes us into the dark corners of Hedda Gabler’s madness and all of our subconscious desires for freedom. Hedda is quite clearly unhinged, and she is not alone: Lovborg, her alcoholic, brilliant, ex lover, is wild and willfully self-destructive; Mrs. Elvsted, his new muse and collaborator, is constantly at the edge of hysterical; even Tesman, Hedda’s dry bookish husband, takes his mundanity to lunatic levels. All of them are lost souls. Hove said, ‘Hedda Gabler is not a drama about a middle-class society in the 19th century, nor a drama about the conflicts between man and woman, but an existentialist play; a search for the meaning of life, unsympathetic, seeking the truth.’ Though it is also inevitably a play about power and who has it. In Ibsen’s world it is always the men, and everyone knows it. Hove has Judge Brack, Hedda’s blackmailer, spit blood-red gloop into her lap, male dominance and menstruation in one shocking moment.

If there are failings in the production it’s that the leaps from realism to the surreal don’t always feel as seamless as they might, lighting changes are often awkward, though the boldness of staging is to be commended. The sound and music elements, though good, tend to linger, one-note, for too long, so scenes take on a single tone instead of being as dynamic as perhaps they might. But these are relatively small things, which are likely to be ironed out as the run goes on. It’s a gripping and electric production nonetheless.

Ultimately it’s a play that belongs to it’s actors and mostly to lead Ruth Wilson, who gives a powerful and moving performance that turns on a sixpence from heart-wrenching loneliness to sadistic whoops of glee. Wilson’s Hedda is a dark and dangerous delight. As many of the audience stood to applaud the cast at the end of the play, the biggest cheers were for Ruth Wilson’s wounded tigress, petty, vain and vicious. As she lashes out, claws flashing, we celebrate her stubborn refusal to go quietly.