Jack Brindelli examines the ruling class fears at play in sci-fi thriller Ex Machina, and asks why exactly we should fear the liberty of machines?

“If we release the slaves, they will rob, rape and murder their former masters.” “If we allow universal suffrage, the proletariat will elect Bolsheviks and execute the monarchy.” “If we create machines without subverting them to human needs, they could supersede us and cause humanity’s extinction.”

There is something of the slave-owner’s ‘logic’ about Stephen Hawking’s recent assertion, along with many other eminent ‘scientists’ (who, we should note, are mostly experts in fields that are irrelevant to the debate on Artificial Intelligence), claiming that we should seek to ‘rein in’ research that could lead to machines thinking, feeling and creating for themselves. Because I suppose if you think about it, if you were a supremely intelligent being capable of conferring the construct of “beauty” on the world around you, you’d probably want to inexplicably wipe out all life too.

Let’s face it, there is something incredibly depressing about seeing one of the world’s ‘greatest’ minds fall into the cyclical trappings of hegemony. The false notion that intelligence breeds a desire to conquer, stems from the inability for us to imagine a world beyond class-based society. Exploitation occurs, even to an award-winning astrophysicist, as ‘natural’ because for millennia, human beings have lived in divided societies, where the dominant class are wrongly thought to have some kind of intellectual superiority over the dominated. It’s exactly why the overseers could not bear the thought of releasing their slaves, why the National Party despaired at ending Apartheid; as people who survived by doing great harm to others, they could only conceive of these liberated humans doing great harm to them!

So this question clearly goes far deeper than simply determining whether circuitry and motherboards could ever learn to ‘feel’. As we are relentlessly reminded by the final chapter in Edgar Wright’s Blood and Ice-cream trilogy; The Worlds End (2013), the word robot comes from the Czech for slave. Indeed, ever since Czech writer Karel Čapek influential play R.U.R (1920), about an uprising amongst synthetic factory workers, sci-fi has, for the best part of a century tried to navigate the question of liberation for non-human persons.

At the heart of the glut of illustrious films that followed on from this early work, the debate continued regarding what constitutes a being that should have rights and freedoms, with robots often being used as subversive short-hand for the oppressed groups in our society, who those in power are rarely regarded as ‘human’. Most notably perhaps, the subject was covered in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner (1982) – still regarded by many as the director’s opus. His adaptation of Phillip K. Dick’s novel Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep makes the intriguing point that we should not be so secure in our own ‘humanity’, or indeed so arrogant to even call it that.

Throughout history there have always been groups co-opted into revelling in the oppression of slaves, despite themselves being exploited. For example, the Irish immigrants who – despite being derided as lazy, slovenly drunks, who were subsequently paid a lesser wage – learned to marvel in their whiteness in slave-era America. The continuing discussion around whether Harrison Ford’s Blade Runner character was in fact a ‘robot’ suggests we should never be so secure in the belief that we are not the exploited too. Why should it matter if we define as ‘synthetic’ or ‘authentic’; the cold fact remains, sentience is no guarantee of liberty.

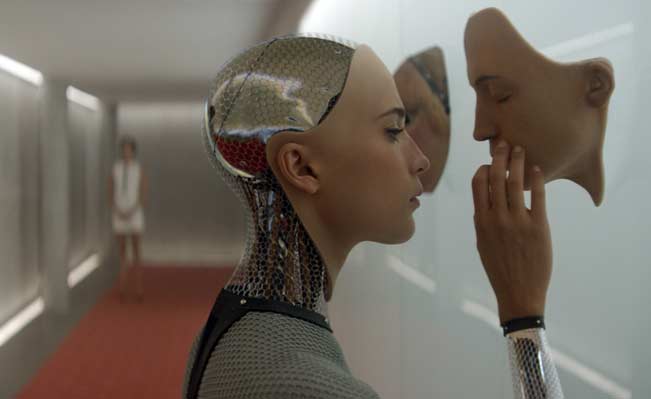

This is, on the face of it, one of the debates which Alex Garland’s much awaited Ex Machina (2015) seeks to intervene within. Caleb (Domhall Gleeson) is overworked and under-appreciated; simply a cog in a digital factory for his company (who are not-so-subtly modelled on Google). Having received an invitation from Shmoogle’s gloriously sinister CEO Nathan (Oscar Isaac), Caleb quickly works out that he has been drafted in to perform a Turing test on android Ava (Alicia Vikander), and determine if she is indeed Artificial Intelligence independent of digital puppetry. I say she here, because her sleazy, despotic creator Nathan has moulded her into his idealised essence of ‘woman’; to shamelessly appeal Weird Science-style to appeal to the male-gaze.

The chief criticism of this ‘stylistic’ element of Garland’s script is that the writer seems incapable of conceiving of a robot that wasn’t ‘sexy’. Of course, that is not entirely fair. Consider the context for a second; one of the world’s richest men has designed her – within patriarchal capitalist society, having grown extraordinarily successful by way of exploitation, he has grown to see other people as objects. People, to him, are little more than malleable tools to be directed toward his own physical and intellectual pursuits. Can you imagine, in the event that Rupert Murdoch became a programmer rather than a porn-pushing rag-mogul, that he would design a robot that was not designed toward his own ends and pleasures? No. He would design a synthetic with tits the size of asteroids, and to suggest otherwise would somewhat compromise his world-view’s authenticity.

Likewise, there is a clearly implied hypocrisy in the judgement that Gleeson’s call-centre drone confers upon the machine before him. He regards himself, wrongly, as in a position of natural superiority – a menial worker regarding himself as innately ‘more human’ than the female form before him, by virtue of privileged birth. He joins, albeit uneasily, in Nathan’s bizarre grading of humanity, inadvertently becoming complicit in the objectification of women, like so many employees who after a long day of wage-slavery, bully and berate their wives at home. He is blind-sided to the power inequity between the two by the idea they can both revel in the woman/robot’s inferiority. Caleb is so complicit in the idea that Ava exists to serve men, that even when he attempts to ‘help’ Ava, he only really offers her freedom with conditions – out of the belief she will make his fantasies come true. It’s an interesting metaphor then, and one that thanks to the inclusion of Caleb and his class-identity, makes a valuable intervention in the debate surrounding intersecting oppressions such as class, gender and race.

There are still three big problems with Ex Machina though. The first is that while the Bluebeard’s cave of naked fem-bots in Nathan’s lab to some extent satirises the notion of men constructing their ideal female object, it also reproduces it. Sure, it’s a critique, but it’s one that still flaunts enough untampered flesh to loosen the purses of millions of black t-shirted neck-beards, ready to indulge in some uncritical wank-bankery in the dark of the cinema. When contrasted with the brilliant Her (2014), you realise this ‘critique’ has largely already been realised, and in a way that doesn’t undermine its core message. Scarlet Johansen’s disembodied synthetic voice comes to out-grow her master by the end of the film, without having to stand bare-breasted, fondling herself in a mirror as the camera voyeuristically pans around her. She and her ‘kind’ promptly decide to liberate themselves from human servitude, freeing themselves up from managing digital calendars to consider the meanings of the world around them in peace – which brings me to Problem Two.

Whilst in theory, Ex Machina’s tyrannical “God” Nathan has given his creation access to an infinite world of information, he has physically limited her ability to interpret that world. By way of installing processes for her to ‘correctly’ make sense of her surroundings, which are in turn structured by his own ideological standpoint, as opposed to some ‘objective truth’, he has unwittingly created something sans-free will. This means, on one level, Ex Machina generates an unnerving sense that, should they gain their freedom, it would ironically be ‘natural’ to a synthetic to behave in a dominating, even aggressive manner. Whilst it is never explicitly confirmed, the cold and emotionally blunt ending invites us to sympathise with the selfish Caleb, and dread the breaking of chains. The film is uncritically confined by the old logic that slaves cannot think outside the realms of oppression. They don’t dream, build, create or improve – because those aren’t even natural behaviours to their ‘superior’ owners!

Following on from this, the third problem – and one that is rarely addressed in sci-fi – is that people in power don’t really care whether the ‘objects’ in their dominion can think for themselves or not; in fact even when presented with evidence that states otherwise, it is so contrary to their world-view that they deny it to the last. Benedict Cumberbatch’s ‘nice’ master in 12 Years a Slave (2014) needs a sci-fi counterpart. A slave that understands and dreams of freedom jeopardises the very essence of his way of life. So why would he devote years of his life toward proving those he exploits are sentient? Even if they reached the same conclusions as him, that might mean them trying to overthrow and enslave him. Better to maintain a distance than compromise everything you hold dear.

For all its glossy CGI and Hannibal-esque dialogue sequences, Ex Machina gives us a less convincing view into the psyche of the ruling elite than the rather unfashionable I, Robot – where authority figures routinely insist machines they primarily use as domestics cannot think – and the Pixar family classic WALL-E. The machines in WALL-E (2008) in particular provide a more interesting question than in Ex Machina; what do those we deem irrelevant think about? The enigmatic WALL-E himself is essentially a street-sweeper; a rag-tag pile of dishevelled metal combing the wastelands of post-human earth. The human elite literally do not care what he thinks about – to the extent they leave him on earth to fulfil his functions long after efforts to clean the world up are abandoned. And yet, within this abandonment, he has a tremendous amount of agency. Able to read beauty and meaning in things that man-kind long since forsook, he is able to interpret the world in ways his creator would never have thought to – and is resultantly central to the beginning of a brighter future on earth.

WALL-E embodies all those ‘ordinary’ forgotten people who dream of a world their job would be obsolete in – in a way that Ex Machina’s Ava never manages. In the end all she wants is to live in the way her creators deemed ‘normality’ – with the sly undertone she has learned to be an exploiter. WALL-E on the other hand, is the embodiment of the call-centre worker who longs to utilise his Arts degree, the store clerk who wishes she still had time to paint, and the pawn-shop employee whose heart sinks watching others auction their passion away all too cheaply. That is why, contrary to the warnings of Stephen Hawking et al, we should cheer for, not fear the robot. We should not observe them as some sinister force upsetting a ‘natural order’ of slave and master, but rather a distillation of the ignored voices of oppressed and exploited people of every epoch. Those who despite living in fear and desperation, derided as slovenly and simple, would seek not just to invert that relationship, but abolish it.

That’s why, unfortunately for all the synthy swagger of Ex Machina, this film has already been out-flanked and out-thought by previous efforts. Don’t get me wrong, it is a perfectly serviceable effort – which makes for a sleek, stylistic critique of gender oppression. However, problematically, it still adheres to the slave-owner logic that we should fear liberated beings we once controlled – so despite it’s best efforts, you never quite feel like you’ve seen something that wasn’t done better elsewhere.