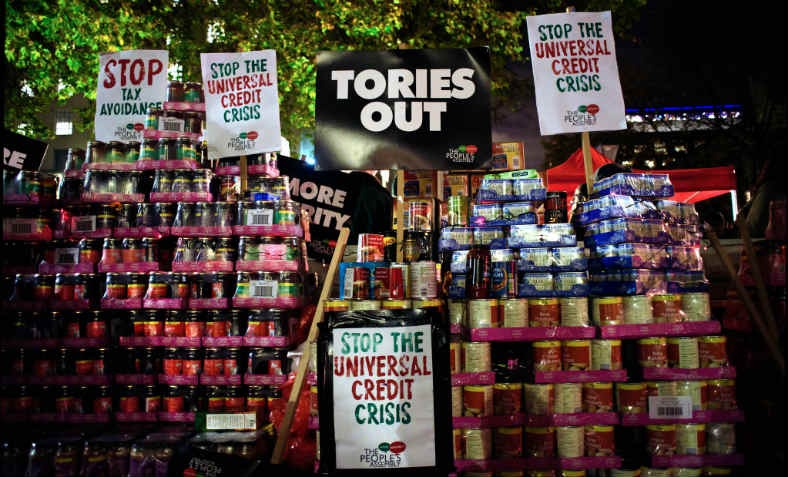

Stacks of canned food donated for foodbanks at the People's Assembly's 'Tories Out' protest demanding an end to the Universal Credit crisis and austerity, outside Downing Street, Nov 21 2017. Photo: Jim Aindow.

Stacks of canned food donated for foodbanks at the People's Assembly's 'Tories Out' protest demanding an end to the Universal Credit crisis and austerity, outside Downing Street, Nov 21 2017. Photo: Jim Aindow.

The latest figures on living standards tell us austerity’s class warfare is more dangerous than ever. Mass struggle is an urgent requirement, argues John Clarke

The impact of austerity is now reaching a point where the effects produce, not just accumulating misery and hardship, but a qualitative worsening of the situation. This is my growing realisation of the situation as both an organiser with the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty (OCAP) in Toronto, and close follower of the situation in the UK (where I lived for many years).

Levels of destitution, hunger and social dislocation are being reached that are as tragic as they are dangerous. This represents a profound challenge to the cohesion and stability of working class communities and threatens to generate a climate of desperation and despair that robs people of the capacity to resist the attacks.

Crisis point

In the UK, where the austerity programme that has been implemented since 2010 has been so especially punitive and damaging, that point of crisis has clearly been reached. On July 24, the Resolution Foundation issued its annual ‘Living Standards Audit’ for 2017-18. The largest rise in poverty since Margaret Thatcher was in power is shown to have taken place.

The poverty rate grew by the greatest amount since 1988. The poorest third of the working age population experienced a loss of income of between £50 and £150. This when inflation for the last 12 months now stands at 2.5%. In terms of child poverty, the situation has been at its grimmest, with a more than 3% increase in a single year and with more than a third of children in the UK now living in poverty. As the think tank points out:

2017-18 was a strikingly bad year for lower income households as the 2015 package of benefit cuts began in earnest, in combination with higher inflation.

The findings of the Resolution Foundation are in line with other research. Last year, a 15% increase in rough sleepers in England was seen and this is the seventh straight year of increase.

A British Medical Journal study looked at premature deaths attributable to austerity measures and predicted 150,000 such tragedies between 2015 and 2020.

The austerity attack: class war by another name

These austerity measures and their dreadful impacts are not merely matters for humanitarian concern. What is unfolding here is not some mistaken or even vindictive set of policy decisions but a very deliberate act of class war.

Ever since the global turn to a neoliberal agenda took place in the 1970s, a key part of this has been a war on the poor. The role of the state in social provision has been greatly reduced and particular importance has been placed on degrading systems of income support.

Since 2010, in the UK, the intensity of this particular attack has been astounding. The benefit sanctions regime, the ‘work capability’ assessments and the brutal rolling in of Universal Credit have drawn international attention. The powerful but, actually, quite understated film I, Daniel Blake gathered audiences in many countries.

This rerun of the New Poor Laws has not primarily been about reduced government spending but about generating a climate of absolute desperation so as to drive people into an expanding low wage sector. In this, the sick and disabled have not been spared.

Here in Ontario, Canada’s most heavily populated Province, governments have presided over a similar exercise. The result has been spectacularly dreadful. In 1997, only one worker in forty in Ontario had to work for the minimum wage, but by 2015 this had gone to one worker in eight.

On both sides of the Atlantic, the aim has been to divide society into winners and losers. The spoils of victory have been considerable and can be glimpsed in some recent research into just how well the FTSE 100 chief executives have been doing, relative to those who work for their companies.

This free ride of the rich at expense of working class people and at such dreadful cost to the poor has left us weaker. Put simply, someone who must rely on charity for their food, who is not sure where they will sleep that night or who sits at home hoping their boss will offer them a few hours work, is hard pressed to imagine that a better world is possible or even that collective resistance is a real prospect. Austerity is, indeed, a human tragedy but it also undermines the capacity to organise and fight back to an enormously dangerous degree.

No hope in moderation

The neoliberal decades have seen the weakening of those organisations working class people have looked to in their lives and struggles. Internationally, trade unions have experienced, not just reverses at the hands of employers and their states but a serious lowering of expectations.

Social democratic parties have often sunk into a condition that we might describe as ‘reformism without reforms’ and have accepted a place as slightly nicer options within an austerity consensus. If an individual name had to be linked to this process, it would certainly have to be that of Tony Blair.

The social democratic New Democratic Party (NDP) in Canada and its Ontario component have not yet broken with that place within the consensus. Across the world, however, people have looked with hope and excitement at the emergence of the Corbyn leadership within the Labour Party.

Certainly, the rejuvenation of the Party base has inspired people enormously here in Canada. The great hope is that a mass based political challenge can be taken up against the sometimes almost triumphalist advance of the austerity attack.

Strength in social movements

I was recently over in London, representing the Ontario Coalition Against Poverty at a magnificent international solidarity summit hosted by Disabled People Against Cuts (DPAC).

John McDonnell addressed the gathering and one thing he said set me thinking. He spoke in terms of a Corbyn led Labour Government working with movements engaged in social struggles to map out strategies and policies. Obviously, that’s very much a position coming from the left of the Party but, it also gets back to historical roots at a time when workers and communities are under severe attack.

The Labour Party didn’t happen because a bunch of middle class careerists got together and looked for a chance to be the ‘progressive’ face of an oppressive system. To go all the way back to the Taff Vale Case, there has always been a sense that those elected in the name of the Labour Party could actually serve working class interests and function as part of something that was much more than a parliamentary clique.

Respect for Corbyn and his close allies is entirely called for but it also needs to be stressed that a serious challenge to the austerity attack will not be achieved and maintained if it unfolds simply within parliament.

The recent despicable exercise in manufacturing an ‘antisemitism crisis’ has seen a response from the Labour left that was sometimes too conciliatory towards right wingers inside the Party and their allies outside it. This attack was as nothing compared to what would be marshalled against a Corbyn-led Labour Government.

I don’t mean this as any condemnation but it simply drives home the point that even the most single-minded left Labour leaders could not hope to proceed with serious measures against austerity without the support and sometimes the pressure of a powerful and determined mass social movement.

In Ontario, fifteen years of incremental austerity at the hands of the Liberal Party have now come to an end and a hard right Tory regime has taken over that is planning to intensify the attack dramatically.

Led by a populist multi-millionaire, Doug Ford, the Tories promised a ‘Government for the People’ and their posturing had its effect.

The NDP (historically similar to the UK’s Labour Party) had not been able to really distance itself from the Liberals. In the previous election, their embrace of the centre led to defeat. This time, they moved significantly to the left and presented an alternative to Ford. It was more of an electoral strategy than a fundamental shift but its effect was startling.

The Liberals imploded and Ford was seriously challenged. On election day, the NDP doubled their number of seats in the Legislature (our regional parliament) and became the Official Opposition.

It proved to be too little to late but had the NDP taken this shift well before the election, thrown its weight behind social movement struggles and used its riding associations (the equivalent of CLPs) as organising hubs for anti-austerity struggles, how much more might have been won?

The NDP leadership, left to its own devices, will rapidly revert to mere parliamentary shadow boxing, rather than use its base in working class communities to help build social resistance, but that is all the more reason for this to be challenged.

The situations in the UK and in Ontario are very different in many ways but there are striking similarities. In both places, the accumulated impact of austerity is at crisis levels and the impermissibility of allowing it to worsen is clear.

There is an urgent need to advance an anti austerity programme, inside and outside of parliamentary settings. Most of all, no way forward is possible in the fight against austerity and its political architects without mass social action on the part of workers and communities under attack.