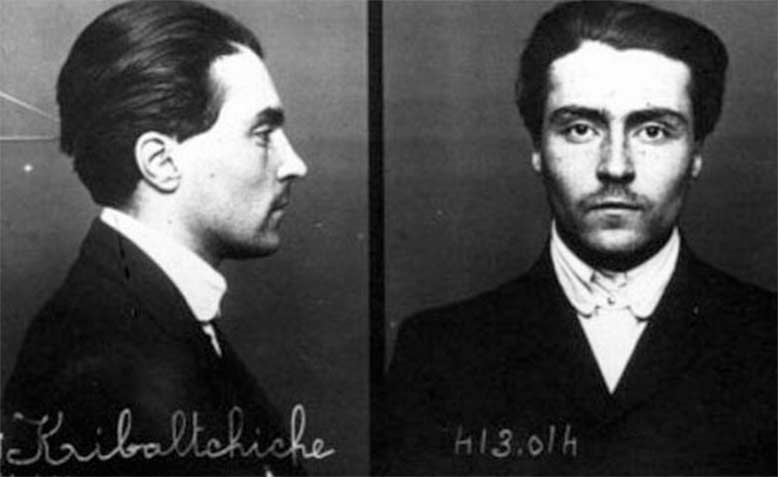

Victor Serge. Photo: PM Press

Victor Serge. Photo: PM Press

Some of the best pieces of fiction ever written about revolutionary experience are outlined by writer and historian John Rees

When I first started to research the Levellers I had it in mind that I might write a kind of collective biography of Leveller activists. I thought of two previous models. One came from the 17th century itself, John Aubrey’s Brief Lives. This is a kind of compendium of short literary biographies of public figures from the century of revolution, written with a gossip’s eye and plenty of verve. His account of the remarkable Leveller ally and MP, Henry Marten, is a joy to read and re-read.

The second was by Anatoly Lunacharsky, who held the brilliantly named post of Commissar of the Enlightenment in the Russian Revolutionary government of 1917. His Revolutionary Silhouettes is a series of pen portraits of some of the main figures of the Russian Revolution by a highly gifted writer and humane observer of people made extraordinary by extraordinary events.

It soon became clear however that this would not be possible. Too much historical context and non-biographical material would be absent, making the account incomprehensible. Nevertheless there is a fair amount of biographical material about the Levellers as individuals and as a related group of activists that has survived into The Leveller Revolution.

But perhaps the place where this kind of interface between individual biography and historical event is best explored is historical fiction. One should never confuse fiction and fact of course. But getting the facts right always requires historical imagination as well as archival research. Moving between historical fiction and historical fact can keep that imagination alive. And that is before we remember that fiction can summon feelings and emotions, sensitivities and responses, which historical writing only rarely touches. Yet these too are historical facts, but ones often beyond our ability to recreate.

In that spirit here are five especially skilful and rewarding fictional recreations of the revolutionary experience.

Englishmen with Swords by Montagu Slater

This is among the best non-factual representations of the English Revolution. It is based on the fictionalised journals of publisher, writer and sometime licenser Gilbert Mabbot. Mabbot has been also been claimed as the editor of the Leveller newspaper, The Moderate.

Mabbot was well placed to know what was going on: he worked under the secretary to the New Model Army John Rushworth and was brother-in-law to William Clarke who took down the record of the Putney Debates. Montague Slater did well to make him the narrator of this novel which retells the events of the high point of the revolution in 1647-49.

Slater follows the action through the final decisive years of the revolution with a rare capacity for reproducing 17th century cadences which seamlessly dovetail with the original material he uses. This is as close as you’ll get to the thrill of the English Revolution as it unfolded and as accurate a picture as many non-fiction histories.

Slater himself was a remarkable critic, playwright and author. He provided the much praised libereto for Benjamin Brittan’s opera Peter Grimes. He was a life long member of the Communist Party, and his novel, first published in 1949, sits in that remarkable period between the Second World War and the 1960s which saw the flowering of interest by left and Marxist historians in the English Revolution.

Spartacus by Lewis Grassic Gibbon

There are no bad Lewis Grassic Gibbon novels and Spartacus is one of the best. It might not have the emotional intensity of his masterpiece trilogy, A Scots Quair, but it is nevertheless more than equal to the historical importance of its subject. In Spartacus we get not just the leader of the slave rebellion in 73 BC but the slave rebellion as a whole.

Grassic Gibbon took the facts of the revolt from the Greek historian Appian. But his special skill is to be able to catch the processes by which exploited people come to political consciousness. He is not didactic because he has an ear for the contradictory thoughts and expressions, and the sheer range of responses, that oppression can provoke in its victims. Boldness and courage are certainly recorded, but so are hesitation and fear, the impulse to resist, but also the instinct to shy away and protect any private peace or personal comfort that can be wrenched from life.

A Place of Greater Safety by Hilary Mantel

Long before Wolf Hall Hilary Mantel was an exemplary writer of historical fiction as this novel proves. Its sometimes said, most famously by Marxist philosopher and critic George Lukacs, that novelists should not try to depict great historical figures but rather view great events through the eyes of lesser known or fictional characters. In general it might be sound advice and there are certainly many historical novels where a well known figure clunks across the pages in a thoroughly inauthentic manner. But A Place of Greater Safety is a triumphant exception that proves the rule.

This is a group portrait of the leaders of the revolution-Camille Desmoulins, George Danton and Maximilian Robespierre. If the characters had been wholly fictional creations they inner feelings and psychology couldn’t be created any more convincingly. Yet it never grates against the known history but seems to deepen our real understanding of it. Mantel adds emotional intelligence to historical fact.

And this book is as tense as any thriller. Of course we know the end of the story. But it doesn’t matter. As the revolution ratchets left our sympathy for the characters and the depth of feeling for their collective fate takes over entirely. We feel the undertow of events and imagine ourselves experiencing them as the actors did…without preparation or precedent.

But this is also a novel about the way that revolution breaks apart the political and personal relationships of those who, at its beginning, were allies but who choose different paths as the revolution throws up deeper and more profound social questions demanding ever more radical solutions.

The Leopard by Giuseppe De Lampedusa

This is not just a great novel about revolution, it is just simply one of the really great novels. Set in amidst the struggles of Mazzini and Garibaldi to unite Italy in 1860 it views events through the eyes of a grand aristocrat and his family in Sicily. The political crux of the novel is about the compromises that the old order must make with the new middle classes if it is not to be swept aside by popular revolution.

The magnificent confrontation in which this is dramatised is between the old Prince of Salina and his nephew Tancredi who goes to fight with the rebels. ‘Don’t you understand uncle’, Tancredi says, ‘everything must change so that everything can remain the same’. Never has the essential question at the heart of the bourgeois revolution be so succinctly expressed. The old aristocratic order must die so that the a new form of class domination can rise in its place.

In the novel this is symbolised by the marriage of Tancredi to the beautiful daughter of the local petite bourgeois mayor, who doesn’t even have a proper dinner suit. Meanwhile the generals are feted in the rich salons for having faced down the threat of popular rebellion.

And, in a relatively rare development, when you’ve read the novel Visconti’s film with Burt Lancaster, Alain Delon and Claudia Cardinale is also a masterpiece!

The Case of Comrade Tulayev by Victor Serge

Serge is one of the great artistic and political talents to come out of the Russian Revolution. An anarcho-syndicalist by inclination and a Bolshevik by experience, Serge is one of the international revolution’s great chroniclers. Fearlessly honest, his Year One of the Russian Revolution should be required reading during next year’s centenary of 1917. His Memoirs of a Revolutionary are a classic. And so too is this novel.

The Case of Comrade Tulayev is a dark tale of the betrayal of two revolutions, the Russian of 1917 and the Spanish of 1936. And it is also one of the great accounts of Stalin’s purges, explaining as no other genre can why people became persecutors, why some capitulated, and how others resisted. What the great novels do that even great history is rarely able to so is to capture the feelings of doubt and fear, of uncertainty and pain, that goes with deep commitment to fundamental processes of change. Serge knew this first hand and he pours it on to the pages of Comrade Tulayev.

Serge’s words from 1943, then chased into exile in Mexico first by Stalin and then by the Nazi’s invasion of France, are one of the great revolutionary testaments: ‘I have undergone a little over ten years of various forms of captivity, agitated in seven countries and written 20 books. I own nothing, on several occasions a press with a vast circulation has thrown filth at me because I spoke the truth. Behind us lies a victorious revolution gone astray, several abortive attempts at revolution, and massacres in so a great a number as to inspire a certain dizziness. And to think that it is not over yet. Let me be done with this digression: these were the only roads possible for us. I have more confidence in mankind and the future than ever before’. Those words could have been written, virtually without amendment, by John Lilburne.