A study of poverty and drug addiction in the slums outside Madrid reveals the callous and destructive nature of the neoliberal city, argues Chris Bambery

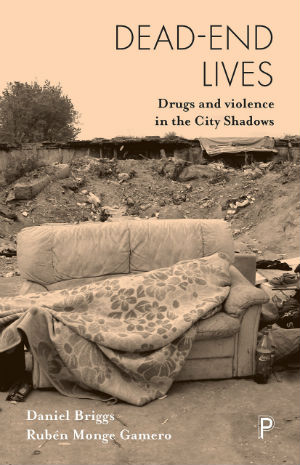

Daniel Briggs and Rubén Monge Gamero, Dead-End Lives: Drugs and Violence in the City Shadows (Policy Press 2017), xv, 301pp.

Today Madrid is the centre of wealth – corporate, financial and personal – in Spain. That wasn’t always the case. A century ago Barcelona in Catalunya and Bilbao (Bilbo) and San Sebastian (Donostia) in the Basque Country were the only centres of industrial development in the Spanish State. Madrid was deliberately built up, first under the Franco Dictatorship and then by successive centre-right and centre-left governments which followed the transition to democracy after the dictator’s death in 1975. It is home to the banks and privatised utility corporations, intertwined with each other, and deeply connected to Spain’s two main parties, the Socialists and the Popular Party.

Yet fifteen minutes’ drive from the city centre lies Cañada Real Galiana, Europe’s largest shanty town, home to some 30,000 people. It is completely lacking in basic public services; there are no pavements, schools, sewage or drainage systems. Many of its people are Romanian, Arab and Gitano (Roma). It lies just south of Madrid along Highway M50, the equivalent of London’s M25 or Paris’ Peripherique.

It is made up of six sectors with the two oldest, Sectors One and Two, created in the 1960s and 1970s by migrant workers from rural Spain. They have public services. Moving south, Sector Three is dominated by the chatarra sector, collecting and selling scrap metal. The quality of housing, roads and services is a step down too. Sector Four is home mainly to Arabs, Africans and Gitanos who run small car repair businesses and other similar workshops. In both sectors water, electricity and gas are illegally supplied in the main.

In Sector Five, the population is mainly Arab and Gitano, children attend local schools and there is a community association trying to improve life, set up after police raids on drug dealing which is evident on a small scale. Sector Six is Valdemingómez, with a population of between 11,500 and 12,500, the subject of this book. Or perhaps more accurately on the lives of two of its inhabitants, “Juan” and “Julia” (as the authors call them.). Since 2007 this has been Spain’s drugs hypermarket and it is a home to many drug addicts.

The beginning of the long financial and property boom in the 1990s saw Madrid force out its old Gitano population with the destruction of the chabolas (shanties) where they had lived on the edge of the city proper. They moved in the main to Valdemingómez, the most recent and under developed sector of Cañada Real Galiana. Some of those families used it as a base for drug dealing. What changed was this went from being a street-corner business to one with its own effective retail outlets and consumer malls concentrated in one small area. It should be stressed there is no moral judgement involved here. The authors are very clear as to how the Gitanos have been marginalised and oppressed, and forced into this situation in order to survive.

The rise of Valdemingómez to become the slum of slums of Spain, and Western Europe, cannot be blamed on those who settled there, but rather on the Spanish state. Traditionally South Madrid is where rural migrants came to escape grinding poverty, so by 1975 half of the city’s population were rural migrants. There was no attempt to deal with this and the result was the emergence of unplanned ghettoes and slums, in and around the large industrial estates established to the south of the city.

In the 1980s, the opening up of the Spanish economy, sealed by membership of the EU, saw the disappearance of many of those old jobs. Employment had to be found instead in the service sector and the booming construction industry. Those jobs were precarious, often seasonal. The gentrification of Madrid saw those workers pushed further and further away from the old inner city.

Then in 2008 came the financial crash, recession and austerity. Unemployment rose to 26.9% by the beginning of 2013, over 55% among the young, wages were frozen or cut, and services cut. Huge numbers were left with mortgages they could never pay off, on worthless or even unbuilt properties. Meanwhile 96% of the social housing stock was sold off. Today the EU claims the Spanish economy has turned the corner, but the jobs being created are overwhelmingly precarious, low-paid and unskilled.

This is a sociological book focusing on the lives of drug addicts, who congregate in Valdemingómez. But the authors grasp the wider reasons for wrecked lives and how neoliberalism is to blame. Thus, they conclude:

‘It is hard not to interpret this as being something quite deliberate, to be honest. Shove thousands of people out to the outskirts of the city, fail to provide for them, forget about them – only remembering to criminalise their behaviour and produce propaganda about their activities in the media … To us it seems like a way of just sending unwanted people to a distant grave, to die quietly in piles of rubbish and waste: dead end lives’ (p.261).

The scale of this in Valdemingómez, Cañada Real Galiana and Madrid is unmatched elsewhere in Europe; Latino migrants compare to what they left behind in Paraguay, Guatemala and Brazil – but it is familiar in most cities, including my native Edinburgh.

This book is not an easy read in so many ways, but it is an indictment of where we are in 2018 and of the Spanish state: Madrid is its show case after all.